Center News

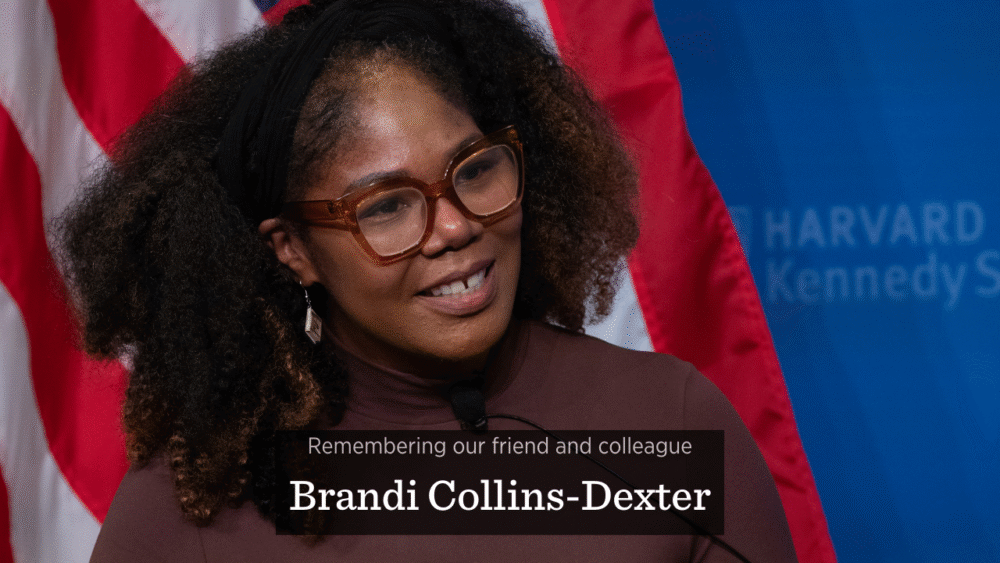

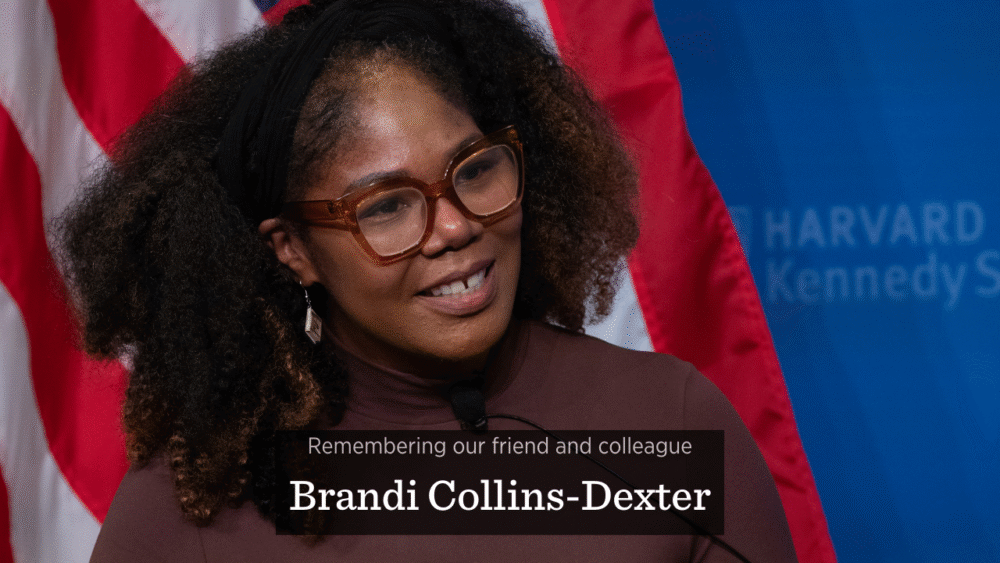

Remembering Brandi Collins-Dexter

The Shorenstein Center’s Research Director Dr. Joan Donovan provides concrete recommendations for public health information officers and communication professionals drafting communication campaigns for health agencies and health organizations to maximize the chance that timely health advisories reach the public.

You can read the full report here.

Dr. Donovan makes five recommendations based on research conducted by the Technology and Social Change project about medical misinformation:

Domain registrars have reported upward of 120 000 domains with keywords related to coronavirus or COVID-19. Although most of the new domains have no content, scammers are using custom domains to target people seeking information about treatment, the worried well, and those suffering financial hardships because of COVID-19 (https://nbcnews.to/3iT5QQu). Public health and health care organizations with already established and functioning Web sites should not register new domains because it is difficult to gain traction within search engines and social media. Instead, these organizations should make a page dedicated to the particular health emergency, in this case COVID-19, on their already existing Web site and update it regularly, even if there is nothing newsworthy to report. Updates provide fresh signals to algorithms, which will rank it accordingly.

Debunking every rumor, every conspiracy theory, and all political punditry exhausts critical resources. Furthermore, there has been a deluge of requests for interviews with medical personnel and public health advocates. Health communicators should establish a monitoring protocol to decide which misinformation is gaining traction and approaching a tipping point, such as when misinformation moves across platforms or someone newsworthy, such as a politician or celebrity, distributes it. We recommend routinely checking the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s rumor database (https://bit.ly/3kSOKUO) and Google’s fact-checking database of recently debunked news stories (https://bit.ly/2Ebnwbg). Scan comments posted to local social media groups and public messaging apps, such as Nextdoor. Keep a log of comments the organization receives via social media accounts, telephone, or e-mail. Importantly, no one should respond to misinformation unless there is good reason to do so and they have a plan for communicating it publicly (https://bit.ly/3j4PKnh). It is recommended not to respond to individuals but rather to debunk major misinformation themes.

Keeping up with the demand for new information during this pandemic will require a shift to mass communication strategies. In terms of risk communication, working with journalists is key to fighting misinformation. Building two-way communication bridges between health communicators and local journalists will ensure visibility and trust across professional sectors when communication emergencies happen. This is different from hosting press conferences. It’s about creating real relationships, where public health is the shared goal. Helping journalists debunk misinformation and providing key recommendations will raise the credibility and visibility of public health recommendations to broad audiences.

If using social media to communicate, which all public health organizations should do, contact the platforms and request free public service advertising. In a crisis like this, online advertising systems can be repurposed to reach local audiences (https://bit.ly/3gcHpfc). Local television news remains a reliable way to inform many people quickly and locally.

Local governments and health agencies should set up text messaging systems and SMS (short message service) push notifications, where possible, to reach people outside social media. Although emergency management strongly advises that governments set up these systems before a disaster, the pandemic is an opportunity to enroll many people. Alternatively, emergency alert systems do not require a sign-up and could be adapted to reach people in a certain geographic area. For example, New York City has used emergency alerts to request health care workers.

Center News

Center News