Download a printable PDF version of this paper here.

The views expressed in Shorenstein Center Discussion Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University.

Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important issues and challenges in media, politics and public policy. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use and shared under the Center’s Open Access Policy.

Author Gabriel London and Harvard Kennedy School Professor Thomas Patterson sat down for a conversation about narrative storytelling in news and common themes between this paper and Patterson’s recent book “How America Lost Its Mind”. Listen to the full conversation below:

Hanging by a Thread

Serialized Narratives in a Post-Factual Era

The current crisis for the institutions of American journalism convinces us of two things. First, there is no way to preserve or restore the shape of journalism as it has been practiced for the past 50 years, and, second, it is imperative that we collectively find new ways to do the kind of journalism needed to keep the United States from sliding into casual self-dealing and venality.1Ricki Morell, “The Making of Binge-worthy Serial Narratives from ‘S-Town’ to ‘Framed,’” Nieman Storyboard, April 4, 2017, https://niemanstoryboard.org/stories/the-making-of-binge-worthy-serial-narratives-from-s-town-to-framed/

Prologue – When Scandal Became Serial TV

They called it “Monica Beach”.

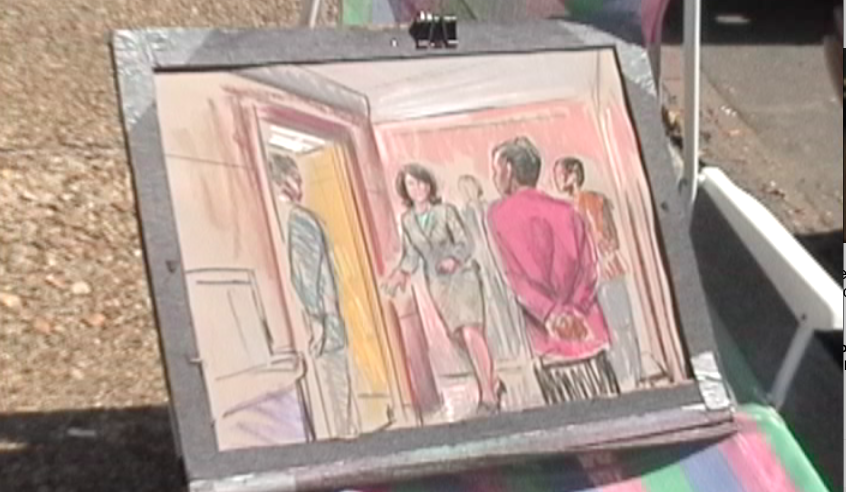

Encircled by news trucks, the ‘beach’ was more of a media encampment on the plaza in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse, where Independent Counsel Ken Starr had convened the Whitewater Grand Jury, as part of his long-running investigation into President Clinton. The TV trucks were hard-wired into the courthouse building, reflecting the semi-permanent status of the stakeout. Miles of cables streamed out from side doors of the building, running this way and that across the public plaza, sustaining individual satellite trucks parked around the block.

In August 1998, the running saga of Starr’s Whitewater inquiry was entering its last act. The focus had long since shifted from the eponymous land deal to the President’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. And while it was vacation time for much of Washington, including for Congress and the President, it was peak season for the running news-cum-soap opera that could have been called The President and the Intern.

On August 19, 1998, I was home from college with a new video camera and setting out as a documentary filmmaker. Idealistic and dismayed that the issues I cared about were getting little coverage in the news, I went to the courthouse to film interviews with journalists on their role in this scandal story. “Why this, not that” was my basic line of questioning. It was the day after a big news event, involving President Clinton’s submission of his DNA to Starr’s team, with rumors flying and speculating after the fact. At commercial breaks the CNN anchors joked about how their broadcasts were sounding more like the Spice Channel. “Can we say this on-air?” Bob Franken guffawed.

The plaza was filled with a mix of idly wandering tourists and impatient reporters lingering under shade-providing tents, just waiting for news from the Grand Jury proceedings. Given their closed-door nature, the press encampment was mostly reduced to reporting on the parade of witnesses, from Monica Lewinsky herself to Linda Tripp’s kids, and the latest leaks and revelations in the twisting tale.

Starting from the courthouse door, a gaggle of reporters could often be seen chasing witnesses (and their lawyers) down Pennsylvania Avenue, until the prey, as it were, could successfully flag a cab and escape.

Around midday, news broke across the plaza in a wave. The action hushed and President Clinton’s voice was heard intoning from TVs scattered throughout. He was delivering an address from a Martha’s Vineyard high school gym, and the solemn nature of the remarks contrasted with the circus-like environment that had just preceded it. Clinton detailed Operation Infinite Reach, the US bombing of an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan and an alleged chemical weapons plant in Sudan. Just weeks earlier, US embassies were bombed in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 200, in attacks that were, in retrospect, an opening salvo in an Al Qaeda terrorism campaign that would lead inexorably to 9/11. This was the US answer.

The two news narratives that day were so starkly different that I looked for changes on the Beach afterwards. But it was just a passing squall; the regularly scheduled programming resumed.

CUT TO:

NBC Today Show (August 20, 1998):

This morning the president will receive the latest US Intelligence analysis assessing the effectiveness of the American strikes. NBC News has learned that at this hour the United States is engaged in a concerted worldwide effort to try to freeze Osama bin Laden’s financial assets, to try to stop him from funneling more money into suspected terrorist activities. All of this comes as questions raised about the timing of Thursday’s strikes. In ordering the attack, aides say Mr. Clinton knew he might be accused of trying to distract attention from the Monica Lewinsky investigation, and he was.

Senator DAN COATS (Republican, Indiana): I just hope and pray that the decision that was made was made on the basis of sound judgment and made for the right reasons, and not made because it was necessary to save the president’s job.

BLOOM: If this all sounds familiar, it is. In a recent movie, “Wag the Dog,” a Hollywood producer, Mr. Moss, is brought in when the president is caught having an affair.

(Beginning of file footage from “Wag the Dog”)

Unidentified Actor #1: What do you think will hold them off, Mr. Moss?

Unidentified Actor #2: Nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing. I mean, you–you–you have to have a war.

Unidentified Actor #1: You’re kidding.

(End of file footage)

BLOOM: But White House aides and US military leaders reject the notion of a “Wag the Dog” strategy.2Anderson, C.W., Emily Bell, and Clay Shirky, “Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present,” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 7(2): 32–123, 2015.

Looking back on those days, a newsy Presidential scandal had become something approximating a serial drama, with clues playing out over time in a story with an indeterminate ending, narratively not unlike a true crime podcast or the TV series that are a driving force of popular culture today. Before the internet’s atomization of audiences, in America circa 1998, across mainstream media from the New York Times to nascent Fox News, the nation was entranced in that narrative netherworld that bingeworthy series tend to induce, hanging on the drip-drip of leaks and evidence that could be embedded in an unwashed blue dress. Not even explosions at American embassies or the first US bombs falling on Afghanistan could awaken us from that sensational revelry.

As a college student at the time, documentary filmmaking seemed like the answer to me: the alarm that somehow could play a part in awakening audiences to issues and policy that were swept over by all-consuming news stories like the Lewinsky scandal. Filmmaking would be a way of introducing counternarratives to the prevailing political stories covered in the media. Looking back over a twenty-year career as an independent filmmaker functioning largely outside the traditional news media, I’ve produced short form “social impact” campaign content on issues ranging from climate change to Iraq and Afghanistan veterans reintegration, and directed feature documentaries on issues of mass incarceration, but have come to see the power of serialized storytelling apart from other narrative formats. Only serials stick with audiences week after week, even year after year, not just informing viewers but also shaping worldviews. Given their open-endedness, serials also have a special application in the political space where they tacitly (and sometimes overtly) encourage a participatory form of viewership that leads audiences to play a part in real world actions, seeking to shape narratives towards elusive, more desirable ends. In this way, I believe serial news and nonfiction narratives have an outsized role influencing our politics and can point the direction towards a more engaged citizenry, for better or worse, depending on the stories being told.

Only once have I employed this type of open-ended storytelling, and it ended up freeing a man from prison. In 2014, after 13 years of work on a documentary about a Florida prisoner with long-documented mental illness seeking parole, The Mind of Mark DeFriest, I found a way to open up the ending of the film in a way that allowed for audience participation in ongoing parole hearings for the title character. At festival and law school screenings in the lead up to a pivotal parole hearing, I guided the audience in ways they could add their voices to the hearing process, including a paper balloting approach that yielded hundreds of votes that we tallied and delivered to Florida officials. Media interest followed this public pressure and, taken together, helped move the Florida Parole Commission to vote for the once unthinkable: parole. In one fell swoop, the Commission took 70 years off Mark DeFriest’s sentence, thereby changing the story itself and compelling me to modify the film with a kind of “happy ending” in time for its broadcast premiere in 2015 (the story has twisted and turned since then).

I saw the engaging power of a story that refuses to end, and in so doing, connected to a narrative approach that works for audiences across the political spectrum.

Through this experience I saw the engaging power of a story that refuses to end, and in so doing, connected to a narrative approach that works for audiences across the political spectrum. In this telling, it is not necessarily about the content of the narrative – left, right or center it can be reflected across the partisan landscape – instead its power derives from the storytelling format: serialization. “A serial is not a form of information delivery. It’s a form of experience delivery. Whether it’s nonfiction or fiction, it’s the creation of a world,” says Roy Peter Clark of the Poynter Institute, pointing out the ability of serial stories to engage audiences in a total vision that goes beyond an informational episode or article.3The Today Show (transcript), NBC, August 20, 1998 Hiding in plain sight, I believe this narrative approach can be seen from conservative Fox News to progressive Solutions Journalism: open-ended, often serialized nonfiction storytelling that engages audiences and helps them enter a world they can affect in ways traditional journalism struggles to do.

In today’s media saturated culture, storytelling itself has become the story. Like Plato’s shadows on the wall, we are enthralled by narrative loops, hanging by the thread of storylines with no end. It’s a Choose Your Own Adventure moment, and the stories we choose – and that choose us – have real implications on how our democracy works. What can this teach those who seek to convey objective fact, hard news, truth? And how can audiences be empowered to see through serial traps, while gaining avenues of engagement that support civic life and the better functioning of our democracy? This paper will endeavor to elucidate this phenomenon of news and nonfiction serialization, revealing pitfalls that can lead to propaganda and enforced narrative walls, while offering positive frameworks for journalists and nonfiction storytellers concerned with the traditional role of journalism to inform audiences in the civic space.

Serial World

Seriality posits a gap in knowing, a delay in disclosure, an interval in storytelling. Its history is in the literary, but that does not make it opposed to evidence-based investigations for truth. Far from it. 4Ryan Engley, “The Impossible Ethics of Serial: Sarah Koenig, Foucault, Lacan,” The Serial Podcast and Storytelling in the Digital Age, ed. Ellen McCracken, London: Routledge. 2017, p. 89

Ryan Engley, “The Impossible Ethics of Serial”

From a media landscape of the few just a generation ago, when the three nightly newscasts commanded tens of millions of viewers, and Walter Cronkite served as kind of journalistic conscience of the nation, we have emerged into a wide-open media space, with narrowcast channel nichification across myriad platforms. Hundreds of local newspapers have shuttered and TV news, with splintered audiences where once there were great concentrations, has largely abandoned intrepid field reporting for cheaper partisan studio punditry.5Marie Clause Foster, “Punditry flowers in the absence of reporting,” Nieman Storyboard, December 15, 2004 https://niemanreports.org/articles/punditry-flowers-in-the-absence-of-reporting/ Mighty media giants have fallen, and new social networks have emerged to occupy American minds with ever more tailored-to-your tastes content, often reinforced by machine-learning algorithms that hone in on preferences to deliver repetitively confirming, and highly engaging messaging.

Ironically, in a time of news and information overload, audiences that could surf the open waves of the new media landscape are instead choosing content that they can come back to, with sustained rather than episodic narratives. From continuous, decades-old storylines on cable news to endless Hollywood sequels, and from true-crime podcasts to Game of Thrones, this is a golden age of serialization. While the mainstream media is evermore consumed by the quick hit of the reactive news cycle, with its breaking news alerts and 24-hour relentlessness, what’s ascendant across platforms from YouTube to Netflix, and media ranging from conservative radio to NPR podcasts, is the slow burn of narrative serials. Observed as a societal phenomenon, it is as though audiences – facing an overwhelming barrage of content from blaring news headlines to the latest product launches – are turning away from the noise to consistent narratives with characters and storylines they can recognize and follow.

Walter Cronkite would sign off the nightly news show by saying, “And that’s the way it is.” Only today, “the way it is” is highly contingent on the channels we choose, and narratives targeted to reinforce those choices.

At the same time, in this wide-open media environment, with nearly infinite content spread across channels, the checks on truth and content-type once provided by limited options and traditional arbiters, like trusted newspapers, have lost ground to competition, partisanship and even presidential broadsides that politicize notions of objective journalism or truth itself. As commonly shared narratives give way to content tailor-made for our tastes, audiences become ever more hooked on storylines that play on ad infinitum, constantly reconfirming whatever informational or ideological points are inserted into the narrative. In what can be called “digital fragmentation”,6Ricardo Gandour, “A New Information Environment: How Digital Fragmentation is Shaping the Way We Produce and Consume News,” Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, 2016 highly tailored news with increasingly partisan political narratives have proliferated, often to the detriment of a shared sense of truth and a common mythology. Exacerbating this phenomenon is what Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris and Hal Roberts label “network propaganda” in their book of the same name: the tendency of partisan, and even mainstream media, to share and reinforce bad information, which is reflected by “induced misperceptions, disorientation, and distraction – which contribute to population-scale changes in attitudes and beliefs.”7Benkler, Yochai, Farris, Robert, and Roberts, Hal. Network Propaganda, New York, US: Oxford University Press, 2018 p33

Ironically in a time of collapsed media gatekeepers, audiences in ever tighter niches appear to be rebuilding the channel walls of the pre-internet, pre-cable, pre-syndicated talk radio era, when limited news options, less frequently delivered were the daily intake. In that earlier era, Walter Cronkite would sign off the nightly news show by saying, “And that’s the way it is.” Only today, “the way it is” is highly contingent on the channels we choose, and narratives targeted to reinforce those choices. Once we reveal curiosities, content creators feed them, producing a feedback loop of content whose nature fits our specific viewing interests, points of view and cultural cues. In many ways, the choice is made for us again and again, pre-populated with storylines that lead one to the next, returning tropes and characters that confirm and re-confirm a message. It is reflected in a breakdown of commonality and trust, a version of what cultural critic, Christian Salmon, calls the ‘storification’ of culture. He writes,

Never before has there been such a trend to view political life as a deceptive narrative designed to replace deliberative assemblies of citizens with a captive audience, while mimicking a sociability in which TV series, authors and actors are the only things that they are all familiar with. Its function is to create a virtual and fictional community. The trend is so astonishingly fluid, so much a part of the times, and so much a part of the air we breathe and the general climate of the age, that it goes unnoticed. And that of course is key to its irresistible success.8Christian Salmon, Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind, New York, Verso, 2010, p95

The power of a “virtual and fictional” community, with the ascendance of charismatic news storytellers and advent of engagement abetted by data-driven social media, takes on real world implications in both online discourse and the offline civic space. And whereas in the past TV ratings and newspaper circulation reflected broad audiences, today’s smaller audience niches are better judged by their engagement than pure size. In her report, “Information Disorder,” Dr. Clare Wardle explains, “The most ‘successful’ of problematic content is that which plays on people’s emotions, encouraging feelings of superiority, anger or fear. That’s because these factors drive re-sharing among people who want to connect with their online communities and ‘tribes.’”9Clare Wardle, Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking, Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex, Council of Europe, October, 2017

This is where I would argue serialization thrives, feeding audiences over time that seek the confirmation of narrative consistency and emotional familiarity, but also the empowerment embodied in stories – often without endings – that they can be part of sharing and even shaping.10Machill, M., Köhler, S., & M. Waldhauser, “The Use of Narrative Structures in Television News: An Experiment in Innovative Forms of Journalistic Presentation,” European Journal of Communication, 22(2), 185–205., 2007. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323107076769 “Serialization… unleashes the considerable power of a desiring, anxious and invested audience in stories that continually defer closure,” writes Erica Haugtvedt in her article on the ethics of serialized true crime.11Erica Havgtvedt, “The Ethics of Serialized True Crime,” The Serial Podcast and Storytelling in the Digital Age, Routledge, 2017, p. 7-23 Whether it’s the well documented “Fox News Effect”12Vigna, Stefano, and Ethan Kaplan. “The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting,” Quarterly Journal of Economics Cxxii, no. 3 (2007): 187-234. on voting behavior, or the phenomenon of audience-led investigations that sprung from the Serial podcast,13Michelle Dean, Serial, One Year on: Web Sleuths Keep Making Discoveries in Adnan Syed’s Case, The Guardian, October 11, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2015/oct/11/serial-one-year-later-adnan-syed-investigation the power of these serial narratives lies in their ability to engage and empower audiences to participate in ways that objective reporting, with its close-ended informational approach, often fails to do.

The implications and possibilities of this evolved narrative landscape are equally fearsome and exciting. As we consider the unknowably vast territory of algorithmically-targeted and serialized content, one can see how audiences can be far more empowered to be part of the story thanks to social media and the format of the news narratives themselves, but equally susceptible to pernicious narrative tricks that work to manipulate rather than to inform more deeply. With the destruction of the media gatekeepers of a previous media age, and the ensuing proliferation of content and channels for engagement, one may perceive a leveling of the media playing field. But in this telling, it is far from equal. Rather, the race is tilted towards the best storyteller.

News at the Crossroads

What really changed was the business model. The 24-hour news cycle, and the fact that news now has to stand on its own two legs rather than rely on classifieds or advertising to keep it going, exposed a lot of deficiencies in the product. If the product doesn’t change places will go out of business, and a lot have.14David Bornstein, Interview with the author, May 24, 2019

David Bornstein, Co-Founder and CEO Solutions Journalism Network

In this new media landscape, competition for attention has never been fiercer or ploys for engagement cleverer. In a previous media era also marked by the popularizing effect of a new technology, television, albeit with much less channel choice compared to today, political scientist Bernard Cohen wrote in The Press and Foreign Policy that the news media “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling readers what to think about.”15Bernard C. Cohen, The Press and Foreign Policy, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963. 13 With the constancy and abundance of narrowly cast narratives today, the ability of storytellers to target audiences and guide them towards what to think about has only expanded further. An algorithm can drive a curious YouTuber, even a well-known sports celebrity, into a flat Earth narrative tunnel where ‘documentary’ after ‘documentary’ is recommended, confirming the conspiratorial worldview of the first.16Des Bieler, “Kyrie Irving Sorry for Saying Earth is Flat, Blames it on YouTube Rabbit Hole”, The Washington Post, October 1, 2018 https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2018/10/02/kyrie-irving-sorry-saying-earth-is-flat-blames-it-youtube-rabbit-hole A noirish yarn can hook a grandmother, who once might have watched soap operas, on a news channel narrative that is replete with the same type of arch characters that return week after week to get up to familiar hijinks. Breaking news alerts delivered throughout the day exclaim endless headlines, snagging us on the latest outrage from an outrageous president.

Not since the travails of the Clintons in the 1990s has there been a character show like Trump’s to follow, and never has news been so popular – driven by political coverage that feeds on outrage.

Whatever the narrative, we are all being served up stories; opportunities to ‘engage,’ all day long. According to a recent Nielsen report, adults spend over 11 hours a day in front of screens, consuming a steady stream of story content across TV, social media and the web.17“Time Flies: US Adults Now Spend Nearly Half a Day Interacting with Media,” Nielsen.com, July 31, 2018. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2018/time-flies-us-adults-now-spend-nearly-half-a-day-interacting-with-media/ Increasingly that content is political, driven evermore by scandal politics and its breakout hit, ‘The Trump Show,’ with the nonstop headlines it generates. In fact, the Trump era has been good for news ratings, offering a very real ‘Trump bump’ that has lifted the fortunes of once sagging media companies, as one might expect if the race to the bottom was the secret to ratings. In October 2018, Axios reported that “politics” was the first place category “for thousands of member websites within the database of leading traffic analytics company Parse.ly [and that] cable news networks have seen record ratings, even higher in select cases than their broadcast counterparts during major events.”18Fischer, Sarah, Axios Media Trends, October 9, 2018 https://www.axios.com/newsletters/axios-media-trends-86a9bc0e-6086-4964-be84-eb659fbfc36f.html Not since the travails of the Clintons in the 1990s has there been a character show like Trump’s to follow, and never has news been so popular – driven by political coverage that feeds on outrage.

For political news, the phenomenon of sensationalism and negative scandal coverage runs the risk of undermining not just the public’s trust in individual candidates or parties, but overall faith in the democratic process itself. In a recent Guardian piece, “How the News Took Over Reality”, Oliver Burkeman articulates the risk of a race to the bottom that eschews policy and real world consideration.19Oliver Burkeman, “How the News Took Over Reality”, The Guardian, May 3, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/may/03/how-the-news-took-over-reality He writes, “In an attentional arms race, every news provider – and ultimately, every news story – competes against all others to worm its way into consumers’ minds… What all this means is that as news comes to dominate public consciousness, extreme, lurid and even false stories come to dominate the news.” As was seen in the 2016 Election, provocative, fake news was shared more than real news.20Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science (New York, N.Y.) 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1146-1151. Sometimes it’s done for profit, as with Macedonian villagers and desktop mercenary types, but other times it’s for more nefarious reasons, as was the case with Russian election interference across the culture.21Eli Saslow, “Nothing on this Page is Real: How Lies Become Truth in Online America”, The Washington Post, November 17, 2018 https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/nothing-on-this-page-is-real-how-lies-become-truth-in-online-america/2018/11/17/edd44cc8-e85a-11e8-bbdb-72fdbf9d4fed_story.html More broadly, following a trend over decades, Harvard Kennedy School professor, Tom Patterson, has studied the increasing negativity of political coverage. In his analysis of the 2016 Election, negative coverage about scandals trumped policy in news coverage throughout.22Thomas Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, December 7, 2016 https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-general-election/ He writes, “A healthy dose of negativity is unquestionably a good thing. Yet an incessant stream of criticism has a corrosive effect. It needlessly erodes trust in political leaders and institutions and undermines confidence in government and policy.” In the end voters can be thrown by negativity or hoodwinked by storytellers, but in either instance they are less informed and less trustful because of it.

Twenty years since the Lewinsky scandal, looking back from an era of 24-hour news, increased partisanship, and fractured audiences across myriad channels, news coverage of American politics has only descended further towards reliance on scandal and horse-race coverage to hold audiences captive. The horse-race aspect, a phenomenon that has reduced the quality of political reporting in exchange for competitive sports-like coverage that eschews policy discussions, is only briefly on hiatus between elections, during which counterprogramming of the scandal nature seems to be the preferred narrative. Oliver Burkeman goes on to make the case for tuning out news that is now pushed constantly across platforms and into phones, as opposed to being consumed periodically as it once was. He writes, “These new incentives favour horse-race politics and hot-button culture-war issues, plus rapid-fire argumentative ‘takes’, designed to confirm readers’ existing prejudices, or trigger scandalised disagreement.”23Oliver Burkeman, “How the News Took Over Reality”, The Guardian, May 3, 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/may/03/how-the-news-took-over-reality Going back twenty years, a Pew Research Center report after the 2000 Election, “Campaign Lite”, articulated the risks associated with horse race coverage that fails to educate voters on much more than tactics:

We have a better understanding than ever before of what is occurring inside campaigns at any moment. We have a stronger understanding of the horse race and more information about the strategies inside the campaigns. We know the “what” of campaigns as never before, but we have little idea why.24“Campaign Lite”, Pew Research Center Journalism & Media, January 1, 2001 https://www.journalism.org/2001/01/01/campaign-lite/

As this paper concerns itself with serial storytelling, the question is whether these narrative approaches of scandal and horse-race fit that picture, as both can be stretched out over time and reflect many of the qualities of serialization, with returning character tropes and story frames, also known as “meta-narratives.” These are familiar to anyone who follows politics, for example, as in the character-shaping media focus on Hillary’s emails that spawned a meta reaction in the #ButHerEmails backlash. After the 2000 Election, “Campaign Lite” argued that these meta-narratives were reducing the quality of coverage, serving as crutches to propel a narrative rather than inform audiences.

Journalists have begun to rely on story-telling themes as a way of organizing the campaign in an engaging manner. They use storylines such as: “Bush is a different kind of conservative.” “Bush is a natural politician.” “Bush is dumb.” “The Bush campaign is in shambles.” “Gore is a stiff.” “Gore is a liar.” “Gore is a political carnivore.” We call these storylines the meta-narrative. As campaigns progress, coverage swings from one meta-narrative to another, and sometimes the storylines begin to contradict each other. The meta-narrative poses grave risks for journalists. 25Ibid.,

But I will argue that beyond scandal and horse-race coverage, and the meta-narratives tied up within those frames, exist serial stories. Unlike meta-narrative character framings, these serial stories are broad enough to stay consistent over time, through varied characters and across topics that can change within a constant narrative. These are open-ended narratives in ways that allow them to sustain a particular worldview and tease out further actions within it. In this way, the news of the day becomes new material for old stories that can be called upon to retain and engage audiences in ways I will come to explore further below.

Questioning Today’s Journalism

Storytelling, then, is born from our need to order everything outside ourselves. A story is like a magnet dragged through randomness, pulling the chaos of things into some kind of shape and – if we’re very lucky – some kind of sense. Every tale is an attempt to lasso a terrifying reality, tame it and bring it to heel.26John Yorke, Into the Woods: A Five-Act Journey into Story, Penguin Books, 2013

John Yorke, Into the Woods

In a competitive media climate with a multitude of content offerings, counterfactual narratives and partisan news often seem ascendant, leading some in the mainstream media to reconsider traditional notions of objective journalism.27Tyler Falk, “Marketplace Reporter Fired after Post Questioning Objectivity in Journalism,” Current, February 1, 2017 https://current.org/2017/02/marketplace-reporter-fired-after-post-questioning-objectivity-in-journalism/ As this is contemplated, I would argue that within the larger frame of scandal and partisanship that has reduced the quality of political journalism, lies a distinction to be made not so much in partisan balance, or questions of objectivity, but in news storytelling formats themselves. In this analysis, whether news is headline-driven in a traditionally reactive way or processed through a kind of serialized format to give it an organizing narrative, lies a key distinction that affects audience engagement and information retention, as well as the broader ability to shape worldviews. “The ability to structure a political vision by telling stories rather than using rational arguments has become the key to winning and exercising power in media-dominated societies that are awash in rumors, fake news and disinformation,” writes Christian Salmon.28Christian Salmon, Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind, New York, Verso, 2010, 100 And in fact, there is a body of research that shows information presented in a narrative format is better retained than when presented in a drier, more informational way.29M. Machill, S. Köhler & M. Waldhauser, The Use of Narrative Structures in Television News: An Experiment in Innovative Forms of Journalistic Presentation, European Journal of Communication, 22(2), 185–205, 2007 https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323107076769 Interviewed for this paper, Pulitzer Prize-winning narrative journalist Tom French explained, “Narratives rend a felt experience, whereas news tells facts and the newest information. Narrative suggests what it’s like to live and die inside those facts.”

Narratives rend a felt experience, whereas news tells facts and the newest information. Narrative suggests what it’s like to live and die inside those facts.

– Tom French

In that sense, we are living (and dying) in an increasingly narrativized world, fed by algorithmic suggestions, push notifications and a blaring media culture that inserts long-running narrative frames into daily reporting. This kind of storytelling engages audiences in the story being told, even as more traditional news formats struggle to retain a diminished share of attention, let alone engagement beyond clicks on the most sensational stories that come and go in a news cycle or two. In this sense, the traditional, timely informational role of journalism leads to the reporting of stories in a kind of isolation, lit by a fickle flame that sputters out too quickly to sustain audience attention or galvanize engagement. In an interview for this paper, David Bornstein, founder of Solutions Journalism, discussed the importance of journalism giving a sense of efficacy along with information, if it is to fulfill its essential civic information function, while also retaining audiences. “If reporting drives fear without a sense of efficacy people will either deny, as with climate change, or tune out. Any issues that come up, people need to understand where is the efficacy around it? ‘What I can I do about it’? Journalism for various reasons stopped halfway.”30David Bornstein, Interview with the author, May 24, 2019

In the face of this phenomenon, the traditional role of the news media to report episodically represents a kind of structural deficiency compared to serial information that is contextualized and offers audiences more to hold onto. According to writer and news audience development expert, Alexandra Leo, “Deprived of context, most news stories begin and end without situating the audience in a broader narrative that could be both informative and more deeply engaging.”31Alexandra Leo, Interview with the author, November 10, 2018 Seemingly recognizing this fact, in Fall 2018, after months of reporting on Russian election interference, the New York Times created a deep dive re-contextualizing insert, “The Plot to Subvert an Election,” with a complete narrative to date of the Russian investigation connected to interference in the 2016 Election.32Scott Shane and Mark Mazzetti, “The Plot to Subvert an Election”, The New York Times, September 20, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/09/20/us/politics/russia-interference-election-trump-clinton.html After all, day-to-day, who could follow the many threads of that story? But even looking back over recent headlines, and given the panicked assessment when it came out, where is the news media still talking about the IPCC report regarding global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels? Or the Khashoggi murder?

Deprived of context, most news stories begin and end without situating the audience in a broader narrative that could be both informative and more deeply engaging.

Alexandra Leo

In this scenario, the mainstream media builds massive audience attention and then dashes to the next big headline, failing to deliver the sustained pathway for engagement audiences crave. Headline stories are media all-consuming until they are flatly not. This has the effect of throwing audiences and squandering their energy to act on information they receive. It denies the public a chance to make long-term investments in news stories that matter to them, and the potential for informative reinforcement that repetition provides. More subtly, it also removes a key element of serial storytelling: the empowered sense of participation, seeking truth and participating in an as-yet-to-be determined outcome. In an interview for Leora Falk’s Harvard Kennedy School paper, “Journalism Raising Its Game — Best Practices for Data Driven Solutions Journalism,” Ethan Zuckerman, Director of MIT’s Center for Civic Media said, “…the internet… is changing the way people expect to consume news… and they will come to expect more information about what to do after reading an article. But journalists don’t attempt to provide a road map for deeper engagement.”33L. Falk, Journalism Raising its Game Best Practices for Producing Data-Driven Solutions Journalism, Cambridge, Mass.: John F. Kennedy School of Government, 2013 Yet such attempts to alter how journalism is performed are limited by the very tenets of objective journalism. As Bill Keller, former executive editor of the New York Times, told me in an interview for this paper, “At the Times, we called them articles not ‘stories’,” with all the implications of agenda and subjectivity tied up in narrative storytelling versus reporting.34Bill Keller, Interview with the author, Sept 14, 2018

Rather than reimagining objectivity, this paper proposes a reconsideration of story formats by looking at the journalistic possibilities tied up in the podcast Serial, as well as the audience activating success of Fox News. Recognizing the limits for journalism reflected in both those examples, I also explore the open-ended and highly engaging approach to traditional reporting represented by Solutions Journalism. Looking at these examples, it is the empowered sense of engagement reflected in their audiences that speaks so much to the moment, and in so many ways reflects the ideal civic role of journalism to inform citizens in a way that enables more effective participation in the civic space. In this way, rather than dismiss the narrative approaches popular with audiences today, we can reframe a conversation around audience retention and engagement away from clickbait tactics to storytelling strategies, asking whether it is about having a better headline story, or a story, better told.

The Fox News Effect – Reframing through Serialization

On Tax Day 2009, Fox News fans morphed into activists, and the activists became marketing vehicles for Fox News. This was the fullest expression of a decades-long trend toward an increasingly partisan news industry, the perfect marriage between a media corporation’s branding strategy and a political movement’s media strategy.35Reece Peck, Fox Populism: Branding Conservatism as Working Class, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019, 6

Reece Peck, Fox Populism: Branding Conservatism as Working Class

With journalism today, beyond the clickbait of headlines, and the bombast of an increasingly frenetic media landscape, lies storytelling, with its fundamental role in ordering a world that can seem out of control. Viewed through that more fundamental lens of storytelling, the highly reactive approach of mainstream media often fails to impose narrative order that would offer audiences a way to process and understand events, while offering avenues of participation. Could journalism that borrows from serial storytelling be an answer? Writing about Serial, a topic I will return to explore, Ryan Engley states, “Journalists, of course, are concerned with ‘the truth’ but few – if any – other journalists consider truth within a serial narrative structure.”36Ryan Engley, “The Impossible Ethics of Serial: Sarah Koenig, Foucault, Lacan,” The Serial Podcast and Storytelling in the Digital Age, ed. Ellen McCracken, London: Routledge. 2017 Perhaps this avoidance of serialization is with good reason, as there are clear pitfalls, as well as possibilities, tied up in this narrative approach. I would argue they are visible on Fox News.

With journalism today, beyond the clickbait of headlines, and the bombast of an increasingly frenetic media landscape, lies storytelling, with its fundamental role in ordering a world that can seem out of control.

In the evolution of Fox News from a so-called ‘conservative alternative’ to privatized propaganda wing of the Republican Party, there remains yet value in analyzing the narrative format that it has chosen to reach audiences over the decades. Across the right-wing media ecosystem, and in particular on Fox, the news plays like a soap opera with established “liberal elite” characters – Soros! Hillary! Pelosi! – and plotlines of nefarious spookiness – the Deep State, Producers vs. Parasites, Government Overreach – that persist as a kind of over-narrative to reframe new headlines in a familiar mold. Despite the chaos of the day’s news, narrative order persists, even while the mainstream media maintains a more frenetic pace. Reece Peck makes a contrast between Fox’s narratives and those of CNN, writing, “Fox’s editorial logic is more strongly organized around the network’s founding narratives and long-term programming themes. In contrast, CNN, like the traditional network news programs, is more readily directed by the short-term editorial agenda of the ‘breaking news’ approach.”37Ibid., 95

Across Fox and the right-wing media, this approach offers a measure of control and comfort over what can be disruptive truths or disturbing stories in the day’s headlines, be it inconvenient truths about climate or President Trump’s self-dealing with foreign powers. The head spinning pace of mainstream news is softened to a narrative pace that, while often bombastic, is nevertheless part of a comfortably known story. Often the timely elements of a headline story fuse with these long-standing serial narratives, enticing audiences with new story points, but consistent character types and constant storylines that are in many ways more entertaining, involving and empowering than news. Think of how each new Russia or Ukraine revelation is instead a Deep State attempt to sack Trump, a narrative that relates closely to a sustained right-wing attack on the power of the federal government. In this reading, the global phenomenon of human-caused climate change is instead a part of a long-running effort to disrupt the American economy and steal traditional American jobs, which when considered from a strict capital perspective relates to the work of conservative media on behalf of big business that dates back to its earliest sponsorship of a right-wing counternarrative in the 1950s (explored so thoroughly in Nicole Hemmer’s Messengers of the Right).38N. Hemmer, Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016

Perhaps at no other time was Fox’s genius in creating and managing serialized, open-ended narratives on fuller display than when they successfully used their storytelling to foment anti-regulatory and anti-government sentiment on the back of the Great Recession. Making the counter-narrative spinning that much more challenging, it was a recession that was in many ways caused by deregulation being re-spun at a moment when the economy required government intervention to survive. Fox not only helped define how Americans understood the financial crisis of 2008, but managed to channel the outrage that flowed from that understanding into massive “audience activations” that fed the Tea Party protests. So even as Obama and Congress tried to pass a giant stimulus package to head off the Great Recession, the effort was handily reframed into a serial narrative about “makers and takers.” Examining in detail how this particular narrative was developed in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis is particularly helpful for understanding the full scope of Fox’s strategies for weaving a long series of news items about seemingly abstract topics of economic and public policy into a coherent over-narrative that not only enables viewers to develop a coherent understanding of the issue at hand (however fraught that understanding may be), but also elicits strong emotions, and successfully encourages viewers to act on their emotions.

Rewriting the Great Recession with Parts for Everyone to Play

At the dawn of the Obama presidency, Fox News faced a challenge it never had. The president and both houses of Congress were Democratic, and there was widespread belief that together they would carry forward a policy of economic stimulus to address the Great Recession. Such a government intervention was antithetical to the conservative, free market economic approach favored by Fox, and the playing field was set for a Democratic rescue of the economy without Republican support. In such a scenario, it would be a return to the policies that had cemented notions of Democratic leadership of the economy from FDR through the Reagan era, and made “It’s the economy, stupid” into a party mantra. At stake was not just the health of the American economy, but also the very progress that the Conservative movement had achieved in rolling back progressive taxation, social programs and regulation since the Reagan era. In his book, Fox Populism, media scholar Reece Peck suggests that Fox was far from ready to cede the economic argument to the Democratic leadership, and instead set out to undermine it with a new take on the Great Depression that called into question the dominant narrative of the Democratic New Deal coming to the rescue after conservative laissez faire economics had failed. In an interview for this paper Peck stated, “There was something about their coverage of the Great Recession that made me realize there was something deeper going on with their message. Something more complicated than a kind of sheer knee-jerk partisanship.”

I would argue that the “something deeper” is an ongoing storytelling approach that rewrites the day’s headlines into running serial narratives, complete with familiar characters and storylines that fit the Fox agenda and activate their audience. In Peck’s analysis of the Great Recession, the characters in the drama were the age old “producers and parasites”, or in Fox parlance, “the makers and the takers.” The characters are consistent, but the actors change with the (political) season, featuring recurring parts like Reagan’s Cadillac-driving welfare mother, who plays a central role in soaking the government. The familiarity bred by such an approach has the effect of not just giving recognizable frames, but also confirming previously heard or felt values for viewers. Viewers can be engaged again and again for a fight against an age-old enemy of their interests – someone who would take, while it is they who make.

Like a drumbeat that builds to a crescendo, Fox understands how to use the serial narrative frameworks at the heart of its channel to vivify political fights in ways that lead towards real world action and impact.

Looking at the three most popular shows on Fox News in 2009 (those hosted by Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck, and Bill O’Reilly), Peck establishes a common narrative throughout the months of debate around the economic stimulus package that was effective in recalling tropes and characters familiar to economic debates (and that, in fact, would be trotted back out for the fight over Obamacare). “Fox programs repeatedly suggested that the financial collapse was the result of ‘undisciplined borrowers’ and Democratic policies aimed at increasing home ownership among low-income citizens and racial minorities. In this way, the network’s framing of the crisis very much played on pre-existing racial stereotypes about welfare-dependency and state-based parasitism.”39Peck, Fox Populism, 157 These stereotypes are embodied by a rotating cast of characters that are featured on Fox whenever the news and policy priorities of the day require it. The faces may change, but not the story.

In the following paragraphs, this paper will demonstrate how overarching narratives are created by employing the same interpretive frameworks across a variety of Fox News programs over time. It will explain how faceless, incoherent groups are turned into vivid, relatable characters — how broad, abstract categories such as the “business community” are repeatedly equated with concrete, easily identifiable archetypes, such as the hard-working small business owner, and how those archetypes are sometimes enacted by flesh and blood representatives on air. This work culminates in a multi-pronged approach through which Fox consistently constitutes the unconventional protagonist of its stories: the viewer her- or himself. In the final read, these serial narrative devices employed by Fox spur audiences to live up to their roles as protagonists, and they help write the ending of the story themselves.

Like a drumbeat that builds to a crescendo, Fox understands how to use the serial narrative frameworks at the heart of its channel to vivify political fights in ways that lead towards real world action and impact. In this way Fox differs from other forms of journalism in that its core narratives are not concrete news stories, but largely abstract arch-narratives that are serialized across a long chain of disconnected political and economic news items presented on the channel. These stories play out with an ever-changing cast of individuals, all embodying a reductive and repetitive set of archetypal characters. This was the approach taken for the 2008 financial crisis, when the engine of Fox’s narrative was the well-established dichotomy of the producers and the parasites, or “the makers and the takers.” This counter position was originally developed by late 19th century labor movements, but back then, workers were understood as the makers and capitalists as the takers. Flipping the script, the modern Conservative movement has adroitly repurposed the framework and argued that the real makers are the “job-creators,” the business owners who boost economic growth and bestow jobs, while the real takers are recipients of welfare and other “unearned” government services. This frame has been in constant use since at least the Reagan presidency, but its appearance across the lineup of Fox’s programming has increased manifold in the years following the 2008 crash. Whether it was on Fox & Friends, The O’Reilly Factor, Sean Hannity or Glenn Beck, guests repeated a common story about freeloading poor people living off of government largesse.i

In Fox’s financial crisis narrative, the primary cause of the crash was not deregulation and greed in the financial sector, but rather the greed of people who wanted to own homes they could not afford. Building the bogeyman character is essential to this blame letting, so in this telling it was the government that “forced,” or the activists that “intimidated,” financial institutions into giving out the risky loans.ii New characters, like Obama was at that time, play a part in a serial story where the government strong arms the free market, in a ceaseless battle against market forces.iii Within the story are key bits of newsy information, namely the repeated invocation of the “Community Reinvestment Act” and supposedly nefarious actors, in this case, ACORN. In this long fight, every Democrat who has ever worked for increasing home ownership could be listed among the culprits who destabilized the economy, but particularly at fault was Bill Clinton, the last Democratic president, and Barack Obama, who in this reading, when working as a community organizer, pushed for extending loans to lower-income people.iv In tandem with this idiosyncratic tracing of the prehistory of the financial crisis, show hosts and guests never failed to emphasize that it would be blameless free market actors who would now have to pay the bill for this government-‘forced’ irresponsibility — if the Obama administration’s stimulus bill went through.

Across Fox News, nearly the channel’s entire ecosystem participated in re-establishing this age-old serial narrative, involving hosts, experts and even educational documentary film inserts (relying on archival footage) that contextualize and deepened the case. In parallel to defining the perpetrators and the primary victims of the crisis, Fox started to flesh out the roles in the story, painting them in vivid details that served to evoke strong primary emotions. Activists who fought for home ownership were painted as intimidating and even as scaring bankers’ children. The “takers” were first of all repeatedly defined as low-income minorities and immigrants, but they also received increasingly specific characteristics, such as “people who may have been addicted for 30 years of their lives” or who “have 4 children by the time they are 21.”v It is worth noting that no matter how specific descriptions tended to get, they always tapped into well-established archetypes, even stereotypes, that viewers would already understand.

In any story, once the bad guy role is filled, the most important character left is the protagonist: in Fox’s telling, that is the freedom loving capitalist who suffers the consequences of the government’s bad actions. In order to effectively fight for its pro-business policy goals, the channel had to develop a persona for corporations that not only allowed easy identification and positive emotional associations, but also positioned them as an underdog, suffering on the same side of the everyman divide. By October 2008, Fox shows were hammering the notion that any government spending to abate the crisis would be money taken out of the pockets of the makers who provide jobs (which, by extension, would make jobs increasingly precarious for workers).vi Corporate CEOs, however, were not to play the part of the makers — in that period, it was small business owners who instead received primetime air day after day. Some shows, particularly that of Glenn Beck, repeatedly created reports on the plight of small businesses,vii while show hosts themselves often assumed the role of industrious, thrifty self-employed people and bemoaned their challenges as if they faced them personally. Real-life small business owners were frequently invoked on the shows, embodying the archetype of the hard-working American striving for independence, and representing the key to creating working class identification with business owners. Reece Peck writes,

Placing the focus on Fox’s media bias narrative in order to understand Fox’s partisan mode of address makes sense if one believes partisanship is fundamentally about representing ideological differences. However, if social background and cultural affinities shape and direct partisan identifications as much, if not more, than pure philosophical beliefs and policy preferences, how the network represents its audience as a sociocultural group requires at least the same amount of scrutiny. Political science scholarship has shown that social identity has a greater influence on political affiliation than ideology.40Ibid., 15

Perhaps the most notable example of this phenomenon is Samuel J. Wurzelbacher, or “Joe the Plumber.”viii In Fox’s universe, the corporate class needed to be firmly equated with hard-working small business owners for the policy goals to fit into the serial narrative of good business vs. evil government. This dynamic is the crux of Fox’s sophisticated approach to character development: it channels diverse, incoherent groups into reductive, firm, immediately identifiable archetypes, attaches strong emotions to them, and personifies the positive character of the story by having show hosts perform it, as well as by finding real-life personalities who can fit the archetype.

This serial story would not be complete without the role played by the audience that seeks clues and information, becoming increasingly empowered to connect dots that could bring about closure. In this case, the ultimate key to Fox’s success in forging audience loyalty and delivering activation is the final step in which it portrays the channel’s viewers as the real protagonists of the story that can make a difference – that the plight of small business owners is their plight, and they are the ones who can do something about it. Sometimes, that connection is even evoked explicitly.ix There are, however, also subtler forces at play. Audience identification with the protagonist on Fox is built on three fronts, primarily: (1) through relatable guest and show performances, as detailed above, (2) continued rhetorical emphasis on viewers’ economic interests, which are equated with the economic interests of the business class, and (3) developing moral arguments, which more often than not, turn the story into a universal battle.

The Tea Party phenomenon represents the triggering power of serial news, which far from numbing an audience through the drumbeat of headline news, rather compels them to beat the drums of a movement in the real world.

Once the reframed financial crisis narrative was set and repeated over the course of months, the Fox audience was primed to assume its role as protagonists in a long-running struggle. In particular, Glenn Beck began leading the charge in calling for direct action from the bully pulpit that was Fox News.x A near direct result was the Tea Party movement, the narrative offspring of Fox’s financial crisis serial. In their paper, “The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism”, Vanessa Williamson, Theda Skocpol and John Coggin argue Fox had an outsized organizing role in the Tea Party movement, writing “Fox News provides much of what the loosely interconnected Tea Party organizations otherwise lack in terms of a unified membership and communications infrastructure.”41Vanessa Williamson, Theda Skocpol and John Coggin, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, Perspectives on Politics 9, no. 1, p25-43, 2011 In this way, the Tea Party phenomenon represents the triggering power of serial news, which far from numbing an audience through the drumbeat of headline news, rather compels them to beat the drums of a movement in the real world. In this case, Fox hosts were all too ready to venture past the informational role of journalism, and instead play an advocacy role that channeled audience energy into events where the screen narratives could leap into the real world. Williamson, et al write,

Fox News has explicitly mobilized its viewers by connecting the Tea Party to their own brand identity. In early 2009, Fox News dubbed the upcoming Tea Party events as “FNC [Fox News Channel] Tea Parties.” Fox hosts Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Greta Van Susteren, and Neil Cavuto have broadcasted their shows from Tea Party events. The largest Tea Party event to date, the September 12, 2009 rally in Washington, was cosponsored by Glenn Beck’s “912 Project.”42Ibid.

While it is discomfiting to think of this type of journalism as anything other than activism, or worse yet, propaganda, it is worth examining what elements of this narrative model could work in another setting, perhaps less politicized and more in the service of news as a public benefit.

The Narrative Tools of Serial

A dispassionate investigation into the physical material of a possible wrongful conviction is certainly a valuable practice, but it can by no means be considered the only way to investigate truth. There must be alternatives available. Serial is this alternative. 43Engley, “The Impossible Ethics,” 98

Ryan Engley, “The Impossible Ethics of Serial”

A narrative order replete with characters and storylines that recall familiar story tropes – good vs. evil, unsolved mystery, shadowy conspiracy – is not the unique purview of the Right. Serial, a podcast from the makers of NPR’s venerable This American Life, proved to be the most popular podcast ever, spawning a movement that long outlasted the original 2014 series of twelve episodes. The popularity of Serial was driven by its highly engaged audience members, some of whom picked up on the clues of the story and further investigated the once dormant legal case of prisoner, Adnan Syed. Delivered in staggered installments that used the narrative tropes of serialization – gaps in knowledge, clues to be connected, lack of closure – Serial served to activate audiences in ways that spawned both online dialogue – on Reddit, in particular – and offline actions – that led to new evidence in the case, even an alibi witness for Syed.44Michelle Dean, “Serial One Year On: Web Sleuths Keep Making Discoveries in Adnan Syed’s Case,” The Guardian, October 11, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2015/oct/11/serial-one-year-later-adnan-syed-investigation Such a level of engagement is remarkable in an era of overwhelming media distraction, and when the accepted wisdom seems to be that attention spans are shortening. In an interview for this paper, narrative journalist Tom French said, “The idea we have about readers or audience attention are wrong. There is more than one way to cover events, and if it’s well done it’s not wasteful.”45Tom French, Interview with the author, November 10, 2018 So what can be learned from Serial that applies to building and retaining audiences for objective journalism, as well as supporting better engagement with long-running societal challenge narratives (i.e. climate change) that are by nature more episodic?

Delivered in staggered installments that used the narrative tropes of serialization – gaps in knowledge, clues to be connected, lack of closure – Serial served to activate audiences in ways that spawned both online dialogue…and offline actions.

Looking at Serial in the context of Fox News, many of the same elements of character development and sustained plotlines exist, yet Serial derives its character narratives directly from the story, whereas Fox works with archetypal characters that are embodied to represent an element of the story. There is a similar vivification of characters in the drama, often missing from traditional news. Through host Sarah Koenig’s interviews and reassembly of detail, characters become relatable, and their actions are sustained in the narrative over time for audiences to follow throughout the series. This richness encompasses Koenig herself, who shares her process, even details of her relationships with subjects including Syed, that play out across the twelve episodes. In opening up the closed case and teasing out doubts about what landed Syed in prison for life, Koenig also implicitly invites engagement in a way that is not unlike Fox’s more explicit Tea Party call to arms. Erica Haugtvedt writes in “The Ethics of Serialized True Crime,”

Serial never explicitly tells people to go out and investigate the case themselves, yet Koenig implies, by drawing upon the generic tropes of fictional crime procedurals and the openness of seriality, that the audience can intervene in this ongoing problem. And when fans do try to figure out the case, it seems disingenuous to not admit this reaction is a consequence of the storytelling choices the podcast has made.46Havgtvedt, “The Ethics of Serialized True Crime,” The Serial Podcast and Storytelling in the Digital Age (2017) 1: p7-21

Serial was a standout event in journalism, spawning dozens of subsequent true crime podcasts, and a reconsideration of serial storytelling, but it did not take away the fraught sense that this kind of narrative work owed more to Victorian fiction than journalism itself. The question arises, then, what can be taken from Serial that applies to journalism today, and how to avoid the ethical questions tied up in Koenig’s choosing to be a storyteller as much as a reporter. In “The Impossible Ethics of Serial,” Ryan Engley grapples with the notion that such an endeavor should be measured on its own merits as a separate narrative form, rather than focusing on how Serial violates the established norms of journalism. Engley writes,

The form of Serial – the genre of seriality – ruptures Sarah Koenig’s reporting, separating it from traditional journalism or documentary filmmaking. When we talk about seriality, we are concerned with endings (how a story wraps up) and when we are concerned with endings, we are concerned with narrative and desire. These concerns separate Serial from the wider world of journalism of which it is a part, and they require a different understanding of ethical reporting to evaluate.47Engley, “The Impossible Ethics,” 88

Can applying a different ethical standard to serial journalism be useful in making it more widely applicable? Evaluating Serial, the essential fact that it follows a search for an elusive truth gives it a moral dimension that recalls Fox’s existential fight frames around the financial crisis. In filmmaking, we would say this “raises the stakes” of the story. Such emotional amplification invites audience engagement, inviting listeners to venture from consuming content into civic action. In this sense, while the storytelling in Serial overlaps with journalism’s role in informing audiences in the civic space, it pushes audiences past that informational role into empowered positions that more easily lead to offline civic actions, be they political, legal or otherwise.

In this way, Serial suggests a way forward for a reportorial style that can yield deeper engagement that both informs and empowers audiences. Koenig refers to herself as a “reporter” and argues she employed journalistic standards in sourcing her story with reassembled trial documents and witnesses.48Ibid. 98 In this way, the conceit that sets Serial apart relates more to format than substance. Following a serial approach, rather than writing a black and white news article on the case with a closed ending, Koenig chose to create a podcast that would let listeners in on her journalistic process exploring a fraught murder case. With a serial frame, Koenig situates her research process front and center as a protagonist’s quest for truth. This contrasts both with the typical third-person objective reporting model, as well as the more theatrical pose of Fox News binary narratives. Joyce Barnathan writes in her piece, “Why Serial is Important for Journalism,”

What makes Serial so special and so meaningful for journalism is reporter Sarah Koenig’s transparency. She takes her listeners along with her as she ponders the innocence or guilt of Adnan Syed. What Koenig does that we don’t normally do is share our thoughts and views as we research a story. Normally we do all that work before publishing. We give our audience the most intelligent assessment we can.49Joyce Barnathan, “Why Serial is Important for Journalism”, Columbia Journalism Review, November 25, 2014 https://archives.cjr.org/the_kicker/serial_sarah_koenig_journalism.php

That ‘intelligent assessment’ aspect of journalism is what can also serve to distance reporters from their audience, creating a handed-down feeling that Serial eschews for a co-discovery process the audience is invited to follow, and even join. Yet what makes seriality such a stretch for journalism are the very real concerns about usurping journalistic standards of objectivity that serve to elevate journalists above the stories they cover, allowing fairness and a cold assessment of facts to occupy what can easily become a more emotional, even judgmental space if one shapes the drama, even becomes a character in it. Ryan Engley further cites a central issue with what can be borrowed for journalism from Serial, writing “…what Barnathan sees as ‘transparency’ others see as a breach of fundamental journalistic ethics. For all its formal innovation, the bulk of the ethical criticism levied against Serial takes issue with the format.”50Ryan Engley, 87

A hallmark of the serial narrative, fully realized in Serial, is not just a suspenseful push to an ending, but a sense of mystery being reassembled; a puzzle solving process the audience can participate in.

Yet it would be a mistake to view Serial in isolation, or to assume the entire approach Koenig takes needs to be borrowed in order to be useful for journalism. Instead, one can look at the discrete notion of context, of which transparency is a major component, and how providing that window on process supports the storytelling process in a way that can have the effect of inviting audiences to further engage. A hallmark of the serial narrative, fully realized in Serial, is not just a suspenseful push to an ending, but a sense of mystery being reassembled; a puzzle solving process the audience can participate in. At worst, of course, that narrative approach can be lent to conspiracies and lead to harassment of real-life characters featured in the drama (as was the case with Serial) or worse yet, ‘self-investigation’ incidents like Pizzagate. But at its best, as I would argue with Serial (and my film, The Mind of Mark DeFriest), audiences can become active participants in the storytelling process, even helping, through their independent actions, to write the ending of an unresolved narrative. That open-endedness stands in stark contrast to the traditional who, what, where, when, why of reporting that begins and ends in a single sitting and is increasingly dependent on sensationalism to compel viewers to watch.

Today’s consumers seek authenticity, transparency and meaningful connections to the storytellers they follow, be they an influencer, a podcaster or a brand, but many of those values important to audiences are left out by reporters, who persist with a more traditional sense of handed-down truth. My argument, in an era when audiences themselves have a publishing voice through social media and seek opportunities to engage, is that it behooves journalists that see themselves as watchdogs of democracy to offer audiences a role in the story. There is something deeply democratic about a journalistic narrative where news consumers are invited to participate, be it Serial or Fox News. Yet, as explored thus far, each of those examples has ethical limits that limit their utility as a framework for tomorrow’s journalism, which leads to a consideration of another journalistic approach that features similar open-ended narratives, Solutions Journalism.

Elements of Serial Storytelling in Solutions Journalism

In a journalistic environment where the mantra “if it bleeds, it leads” continues to resonate—and is amplified ever more by the clickbait web—there is a professional bias in favor of reporting on violence, crime, police brutality, and other negative tropes. But how do audiences process and react to stories about their communities presented within negative frames? How would stories that address these systemic problems—while also exploring their solutions—impact readers?51Andrea Wenzel, Daniela Gerson, and Evelyn Moreno, “Engaging Communities Through Solutions Journalism”, Columbia Journalism Review, April 26, 2016. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/engaging_communities_through_solutions_journalism.php#research-findings

“Engaging Communities Through Solutions Journalism”

In this telling, a journalistic approach that engenders audience agency and engagement is what connects Solutions Journalism to Serial and Fox News. Be it the opioid crisis or the question of scarce resources for a school system, Solutions Journalism opens up the ending of articles that would normally close out their informational approach with the who, what, where, when, why of a story, with the ‘how’ of potential solutions.52Solutions Journalism Story Tracker, Opioid Articles https://storytracker.solutionsjournalism.org/search?q%5Btext_search%5D%5B%5D=opioid&q%5Bfull_text_on%5D=false In this sense, a door is opened at the end of the story, rather than closed with the conclusion, and that is what relates the narrative format of Solutions Journalism to serialization, with its delayed endings. Founded by New York Times reporter, David Bornstein, this approach works as a kind of answer to the dispiriting question of what to do with the finality of close-ended reporting that both denies avenues for further engagement, and often keeps headline news decontextualized from a larger narrative. In an interview for this paper, Bornstein suggested, “If reporting drives fear without a sense of efficacy people will either deny it, as with climate change, or tune out. But with Solutions Journalism, we bring in any solutions that may be relevant, grounded in evidence. People need to understand, where is the efficacy around it, ‘what I can I do about it’?”53David Bornstein, Interview with the author, May 24, 2019 The concept is simple: start by opening up the ending of traditional articles and include potential ways to address the topics raised in coverage. In this way, an article about opioids devastating a community would offer up rigorously researched solutions tried in other communities facing similar challenges.

In a news space that is awash in negativity, particularly as it relates to the horse race and scandal aspects of politics, Solutions Journalism represents a formula for engaging news audiences in seeking out positive outcomes.

In a news space that is awash in negativity, particularly as it relates to the horse race and scandal aspects of politics, Solutions Journalism represents a formula for engaging news audiences in seeking out positive outcomes, not unlike audiences for Serial or those that watch Fox. Bornstein articulated how the information-rich Solutions approach contrasts with a “CNN Heroes” model, which tends to focus on a single person in a low-information celebratory piece. He says, “The storytelling format is something we call a ‘how done it.’ It’s a quest narrative, and actually if you compare it to other forms of literature, its closest comparison would be the detective story or a procedural TV drama, like Law & Order or CSI, or even books like Harry Potter.”54Ibid., In playing with storytelling formats, Solutions reflects a willingness to push the boundaries of traditional journalism, asking how audience engagement can be fostered without resorting to sensationalism.

Rather than competing against the popularity of negative news and scandal, Solutions Journalism posits that there is an audience for ‘how’ stories that move beyond the problems that grab headlines, into the solutions that can help shape communities for the better. Returning to Bornstein’s point about the importance of efficacy, this kind of journalism empowers audiences with potential tools to solve problems that presented in the traditional headline format, without options to act, might turn them off from news or a given issue altogether. Bornstein writes, “Much of the time, reporters spotlight problems – i.e., provide negative feedback – with the goal of spurring reforms. To be sure, this watchdog (or disinfectant) role is essential. But increasingly, we’re coming to see that it is also incomplete.”55David Bornstein. “Up for Debate: Why We Need Solutions Journalism”, Forbes, November 29, 2012 https://www.forbes.com/sites/skollworldforum/2012/11/29/up-for-debate-why-we-need-solutions-journalism/#699c3ed25b75 Instead the ‘how done it’ frames of Solutions stories are engaging in a way that recalls the incredible popularity of how-to instructional videos on YouTube.56Aaron Smith, Skye Toor, Patrick Van Kessel, “Many Turn to YouTube for Children’s Content, News, How-To Lessons”, Pew Research Center, November 7, 2018 https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/11/07/many-turn-to-youtube-for-childrens-content-news-how-to-lessons/ In fact, in their report,“Engaging Communities Through Solutions Journalism,” Andrea Wenzel, Daniela Gerson, and Evelyn Moreno, establish that “Preliminary research suggests… “Preliminary research suggests readers of solutions-oriented stories are more likely to share articles and seek related information.”57Andrea Wenzel, Daniela Gerson, and Evelyn Moreno, “Engaging Communities Through Solutions Journalism”, Columbia Journalism Review, April 26, 2016. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/engaging_communities_through_solutions_journalism.php#research-findings

With Solutions Journalism, like a serial, the ending is held at bay as long as we remain in the fight, trying to take the wrongs in the story and make them right. Bornstein writes, “A Solutions Journalism story should show you a method by which some organization, policymaker, or a group of individuals, attacked a problem, got different results and there’s a teachable lesson. That’s a really useful story with a long shelf life as well.”58David Bornstein, Interview with the author, May 24, 2019 When Oliver Burkeman and other writers talk about news fatigue, and so many of us are familiar with those that have chosen to ignore the news for mental health reasons, Solutions Journalism holds out the possibility of remaining engaged by refusing to succumb to a sense of powerlessness. Rather than running from tough day-to-day issues, Solutions points out a way to cover challenging topics without resorting to sensationalism.

Storytelling the Truth

I think it’s important to remember that you actually have to create the facts. You can’t just say ‘that fiction is wrong’, ‘that fiction is wrong’, ‘that other fiction is wrong’. You actually have to have institutions that create facts and can pump some of those facts into the public sphere, so at least they have a chance. We have this mistaken view in the whole Anglo-Saxon philosophical tradition – we think that the facts are out there and in a fair fight they’ll win. But they’re not out there. They have to be produced and pushed into the fight, if they’re going to have a chance.59Timothy Snyder, quoted from The Good Fight with Yascha Mounk, Slate. November 7, 2018

Timothy Snyder