The views expressed in Shorenstein Center Discussion Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University.

Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important issues and challenges in media, politics and public policy. These papers are published under the Center’s Open Access Policy. Papers may be downloaded and shared for personal use.

Download a PDF of this paper here.

Introduction

The Chernobyl comparisons began in March, in response to Russian government updates on the spread of COVID-19 cases.

“Everybody’s talking about, ‘Oh, it’s Chernobyl again,’ ” one young Russian skeptic told The New York Times.

“I do not trust these figures,” the editor of an independent newspaper in the Russian city of Kaliningrad told the Committee to Protect Journalists. “I remember Chernobyl, when [then-Soviet] authorities tried to hide the truth.”

A prominent liberal commentator expressed his doubts to both Russian and Western media. “It’s a tradition for Russia since Chernobyl — to hide the truth,” Valery Solovei told ABC News, not long after he’d made similar remarks on the influential Russian radio station Ekho Moskvy. In his March 16 Ekho interview, Solovei cited numbers of coronavirus cases and deaths that were significantly higher than Kremlin officials acknowledged. When Russia’s media regulator Roskomnadzor ordered the station to remove the interview, “to prevent the spread of false information related to the coronavirus,” Ekho complied.

The memories may be 34 years old, but for many Russians the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster remains shorthand for government lying and censorship. It happened in a country, the Soviet Union, whose Communist Party leaders exercised such ruthless control that they could maintain a three-day, total news blackout about the explosion — even as European neighbors recorded high levels of radioactivity drifting westward. When party leaders finally made their first public acknowledgement, media were only allowed to report these details about the deadly disaster: “Measures have been taken to eliminate the consequences of the accident. Aid is being given to those affected. A government commission has been set up.”

Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin, gripped by a different crisis in 2020, the spread of COVID-19, may have wished for that kind of control. Indeed, the Kremlin does hold a Soviet-like grip on Russian TV, where the leader and his policies are never wrong.

But today’s Russian media is not a Soviet-style monolith. That was clear in the spring of 2020 as the pandemic unfolded and its story was told by many voices on multiple platforms – by Russian medical workers on social media, by bloggers and tiny news sites in remote regions, by recent independent news startups led by some of the country’s most respected journalists, and by some older outlets that still manage to tell true stories in spite of Kremlin pressures.

It would be an exaggeration to call this period in Russian journalism a renaissance; even those optimistic enough to launch the newer startups know how fragile their existence is in a country whose press freedom record ranks a dismal 149th out of 180, according to Reporters Without Borders. A grim reminder of that vulnerability came in the summer of 2020, just days after Putin won constitutional changes that could keep him in office for another 16 years. Security agents arrested a highly respected former investigative reporter, Ivan Safronov, charging him with treason in a case that many believed was politically motivated – and could signal the start of a new round of anti-press repression.

While that news was chilling, the response from Russian journalists was striking. Dozens quickly leapt to Safronov’s defense, and to the defense of the independent journalism and investigative reporting that have been growing, in a place where just five years ago both were considered all but dead.

I am one author who wrote an obituary – prematurely, it turns out. My 2015 essay was titled “The Death of Glasnost” – glasnost, or openness, being Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s term for how he planned to curb his Communist Party’s 70-year-old policy of feeding lies and propaganda to a population ruled by fear. [i]

I began watching the Soviet media system when I arrived in Moscow for the first time in December 1986, a few months after the Chernobyl explosion. Over the next five years, as NPR’s Moscow correspondent, I wrote frequently about glasnost, as Gorbachev worked to persuade his Communist colleagues to loosen their censorious grip on information. By the time Gorbachev resigned and the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, media in newly independent Russia had entered a “golden” period of freedom.

Golden, but also very brief. Years of financial and political chaos in the 1990s led to a downward spiral. And then, in 2000, with Vladimir Putin in the president’s seat, Russia’s government opened a long, systematic assault on a free press.

By then I was watching post-Soviet Russian media from a new perspective, as a press freedom advocate. Journalists were increasingly squeezed by laws and policies that forced them into new forms of censorship. Those who didn’t curb their work risked violent attacks, even murder. The threats to journalists and independent reporting felt as dire as the Soviet era’s rigid regime of prior censorship. Glasnost seemed an ancient memory.

Glasnost was my reference point as I began research on Russian media at the Shorenstein Center in early 2020. Why hadn’t it led to a lasting free press that could serve as Russia’s Fourth Estate? Why were media so unprepared for the rough-and-tumble 1990s in Russia, and what made them even more vulnerable to Vladimir Putin’s anti-press efforts? And after all these years, what legacy, if any, remained of glasnost?

The COVID-19 pandemic offered a window into examining the legacy question, and for several weeks in the spring of 2020, with the help of researchers at Harvard Kennedy School and in Russia, I focused on coverage of the crisis by a range of Russian news sources. In the work of some, we found that legacy – newsrooms producing strong, public interest reporting on a crisis that threatened lives and livelihoods across Russia.

Most news outlets that fit that description are small, just a few years old, available only online, and potentially vulnerable if the Kremlin chooses to launch a new crackdown. And news consumption surveys by the country’s most reliable pollster show these sites reach relatively few older Russians, who remain glued to Kremlin TV.

But the same pollster, the Levada Center, shows Russians in their 20s and 30s are turning off TV news. Online sites and social media are their main news sources, a fact that likely causes Kremlin concern but is hopeful news for independent journalism.

“Young people, at least younger people, no longer succumb to all this propaganda TV,” said journalist Yevgenia Albats, who has endured years of Kremlin attacks for her investigative reporting in independent media. [ii]

“The most important instrument of propaganda for the Kremlin is the state-owned big TV channels,” said Sergei Parkhomenko, who became a journalist in the heady days of glasnost. Thus, the loss of younger audiences “is a very huge problem for the Kremlin.” [iii]

This study examines the evolution of independent Russian media, from the glasnost era to the pandemic. It describes some of the pandemic coverage and identifies several of the newsrooms that gave Russians reliable, accountability journalism throughout the early months of the crisis.

It may seem obvious that the survival of this journalism is vital for Russian audiences. But foreign audiences also have a stake in truthful reporting that can help us better understand Russia. For foreign governments and their diplomats, independent reporting can be crucial for shaping foreign policy. And for journalists working in other countries where press freedom is under threat, the struggles of Russia’s independent media may offer inspiration and some possible lessons on how to survive.

CHAPTER ONE: GLASNOST

Beginnings

For audiences long accustomed to searching Soviet media for nuances, there were signs of change almost as soon as Mikhail Gorbachev ascended to the post of general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985.

That May, when Gorbachev visited Leningrad, Soviet TV showed his meeting with local party officials, an event normally hidden from the public. TV cameras also followed him to an unscheduled street stop, where the Soviet leader waded into a crowd, chatting and smiling, unafraid to field spontaneous questions. The TV audience could see clearly that the country had a very different leader from the doddering line of party men who had preceded him.

Gorbachev later labeled the Leningrad trip “the first act of glasnost,” according to Russian journalist Natalia Rostova. In her digital chronicle of the glasnost years, called The Birth of Russian Media, Rostova noted that while 1985 brought few concrete changes to Soviet media, “a wind of hope appeared.” [iv]

Hope indeed had appeared, but a coherent, carefully crafted glasnost policy had not – and never did. Throughout the Gorbachev years, glasnost remained an idea riddled with contradictions. Its precise meaning and boundaries were never clear, though it was clear that party leaders, including Gorbachev, intended boundaries. And they never stopped trying to set them.

“Many times Gorbachev made it quite clear that glasnost was not the same thing as unbridled freedom of the press,” [v] wrote Scott Shane, who covered the glasnost era for The Baltimore Sun. Gorbachev’s goal, said Shane, was “to renew socialism, not to destroy it, to make the empire stronger, not to break it apart.” [vi]

To do that, Gorbachev needed to lift the curtain on lies the Communist Party had told for decades about Soviet economic and social progress. Only when the public understood the true state of affairs, he reasoned, would people support the ambitious, potentially painful set of economic and political reforms that he called perestroika, or restructuring.

Put more bluntly, said Shane, Gorbachev saw glasnost as “a blowtorch that could strip the layers of old and peeling paint from Soviet society.”

A few months after I arrived in Moscow, an early version of that glasnost “blowtorch” debuted on Soviet TV. Spotlight on Perestroika featured 10-minute segments, broadcast after Vremya, the country’s premier TV news program that was watched by tens of millions every night. In a December 1987 story for NPR, I noted that Spotlight gave viewers “glimpses of life as it’s really lived in the Soviet Union.” [vii]

My NPR piece focused on a Spotlight story by reporter Yevgeny Orlov in the southern Russian city of Astrakhan. Orlov began with a scene familiar to all Soviet shoppers (but seldom shown in Soviet media): a long line outside a state store where a woman said she’d already waited for hours and was still half a kilometer away from being able to buy a head of cabbage. From there, Orlov made his way through the produce distribution chain, asking drivers, port authorities, and finally the local official responsible for agriculture why the stores were so empty. “Steps are being taken” was the lame, but typically Soviet, response of the agriculture official.

Orlov’s story didn’t hold any of his sources accountable. Instead, he closed his Spotlight investigation with a vague plea for reform of the food supply system. In my NPR narration, I said the reporter had pulled his punches, as Spotlight segments often did. I asked Orlov about that when I interviewed him for the story, and he gave me a statement of purpose at odds with the watchdog ethos of newsrooms where I’d always worked.

“Journalism is the main helper of Gorbachev as he tries to right the wagon, the cart, whatever you want to call it, from its present place,” said Orlov, a graduate of Moscow State University’s journalism faculty. “Every person, every journalist has a conscience and has a feeling of patriotism, a love for this motherland. He now needs to understand his role in what’s laid on his shoulder: that without glasnost, without the press, we could hardly do what this country needs to do.”

Acceleration

The notion that journalism existed to serve the party and its policies was deeply baked into Soviet media. At the same time, Soviet journalists often knew far more about their communities than they were allowed to write. When I visited newsrooms in Perm, Krasnodar, Izhevsk and other Russian cities, reporters often were happy to share tips on stories they knew they could never get past the censors. But a few were also beginning to interpret Gorbachev’s calls for glasnost as a green light to do their own, more aggressive, reporting.

Two journalists in particular, editors Yegor Yakovlev at Moscow News and Vitaly Korotich at Ogonyok – both appointed in the months after the Chernobyl coverup debacle – seized the early glasnost period to launch what eventually became an information revolution. Both publications came out weekly, and week after week they stunned readers by publishing stories about police torture, prostitution, drug addiction, the failings of the Soviet war in Afghanistan or the long-buried secrets of Joseph Stalin’s repressions.

Yakovlev and Korotich, both middle-aged, hardly resembled revolutionaries. Like all Soviet editors, they were Communist Party members, appointed to their posts by the party’s top leadership. The leaders treated media as an arm of the party, regularly calling editors to the Kremlin to issue orders or chewing them out by phone when stories “went too far.” Those practices didn’t stop during glasnost; Yakovlev and Korotich each fielded plenty of angry calls, as did many of their colleagues.

In the summer of 1987, over tea at his Moscow home, I talked with Korotich about instructions editors had recently received for commemorating the upcoming 70th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Certain topics were listed as “inappropriate,” he said, and these included assessments of Stalin-era crimes. But it was already too late to rule that off limits; months earlier, Korotich’s magazine had published excerpts from Children of the Arbat, a long-suppressed novel about Stalin’s terror. It was one of the many glasnost-era sensations that ensured Ogonyok routinely sold out its weekly print run.

Korotich told me editors at other publications had warned him that by pushing so hard, he was moving quickly beyond Gorbachev’s vision of glasnost. “Many of my colleagues speak in such a way: ‘Please, don’t be so sharp. Wait a little. Wait a little, because you know we are going to [have a] big Soviet holiday, to our 70th year of revolution,” he said. [viii]

Korotich’s affable candor could almost convince you that he knew exactly how far he could go – what he could publish without being fired or otherwise punished by the party. In fact, the process was never so clear cut. Every week, it seemed, journalists pushed past some old taboo and then held their collective breath to see what would happen. If the Kremlin reaction was no worse than shouted complaints (which was most often the case), many pushed forward on new topics.

Years later Korotich told Russian journalist Anna Arutunyan: “We were experimental airplanes that the government decided to launch. If we flew, great, but if we started floundering, no one was going to come to our rescue.” [ix]

Breaking Free

Though Ogonyok and Moscow News were early leaders, rival publications quickly began to match them, assigning their own staffs to investigate “blank spots” in Soviet history and address societal problems long swept under the censor’s rug. Circulations soared, even for some of the more staid Soviet publications, as a public starved of information for so many decades devoured every new revelation.

Meanwhile, many party conservatives howled in protest. In a typical attack at a 1989 meeting of the party’s Central Committee, one official fumed that Soviet media was now “full of prostitutes, drug addicts, hooligans” who were “morally corrupting our people, and first and foremost the young.” [x] Liberals were usually less florid in defending the new openness, at least in public. But behind closed party doors, debates on the meaning and limits of glasnost raged for years.

Gorbachev, the policy’s initiator, often only added to the confusion. “At times he upheld the more liberal policy direction,” wrote academic Ellen Mickiewicz, “and at times, he countenanced the opposite. It depended on the political strategy of the moment and on an enduring conviction of the rightness of socialism as he understood it.” [xi]

No medium got greater scrutiny or caused more consternation in the party hierarchy than TV; 93 percent of Soviet households watched TV in the Gorbachev era, according to Mickiewicz, making it by far the most influential information platform. And no program caused the party more heartburn than Vzglyad, a Friday late-night show aimed at youth that routinely “pushed the bounds of freedom of speech well beyond the Party’s toleration,” Mickiewicz wrote. [xii]

I have sometimes called Vzglyad the best TV journalism ever, anywhere. I’m remembering it, of course, in the context of that extraordinary time, which informed and energized the three young hosts and their huge national audience. An episode of Vzglyad could move seamlessly from music video, to political revelation, to sharp-witted humor. Because masses of viewers tuned in each week, its programs often sparked national conversations: about Communist Party privileges, or the failure of Gorbachev’s economic reforms, or whether Vladimir Lenin’s heavily embalmed corpse should finally be removed from its Red Square mausoleum and given a burial (the latter idea, considered heresy by many party members, led to the firing of the head of state TV, but Vzglyad’s hosts remained in place).

Scott Shane described the hosts as “surfers riding the advancing wave of glasnost, masterfully judging just where the edge of the permissible was located and trying to stay just ahead of it.” [xiii] When they did reach too far for party leaders, censors would snip an offensive segment, or yank the show off the air – but only temporarily.

By mid-1990, said Shane, Vzglyad had moved beyond revealing Soviet secrets to focus on showing viewers how their lives compared with the West. On Soviet TV, life in the homeland had always been portrayed as fine, even wonderful, while Western capitals were hotbeds of poverty and homelessness. Vzglyad’s prism reversed things. In the West, manual laborers felt free and earned enough to buy cars and comfortable homes; in the Soviet Union they struggled just to keep food on the table.

That message was deeper, and more dangerous for the party, than the one presented in Spotlight on Perestroika segments just three years earlier. Spotlight looked at a narrow problem like empty grocery shelves, while “Vzglyad often asked about the system that permitted such problems to occur,” wrote Shane. If the earlier program offered a targeted spotlight, “Vzglyad was more like broad daylight, and in daylight the [Communist] system appeared to be beyond saving.” [xiv]

In fact, by 1990, it felt like there was little about the system that journalists had not exposed to daylight, and the system was feeling the consequences. As people learned more, they spoke and acted more boldly. Coal workers went on strike over the abysmal conditions in their Siberian mines. Parents in heavily polluted cities like Magnitogorsk organized environmental protests. The faithful gathered in greater numbers, in the few Russian Orthodox churches the atheist Communist Party hadn’t blown up or turned into warehouses. In these and so many other stories I was covering, there was a clear subtext: the fear that enabled party control was disappearing.

That subtext reached something of a climax in 1990, during the traditional May Day parade that had long been a highly choreographed paean to the Communist worker. That year, the public was invited to join in, and among the newcomers who marched past Gorbachev and other party leaders on Red Square were Hare Krishnas, Stalinists, radical democrats, anarchists and a small group yearning for a return to Russian monarchy.

“Never before had Soviet citizens so boldly confronted their leaders,” I said in an NPR story on the disappearance of fear. Many in the May Day parade waved their fists and shouted “Resign! Resign!” at Gorbachev and his colleagues. “The initiator of glasnost, the man who promised democracy, had had enough,” I said, describing how Gorbachev and the other party leaders turned their backs and left the square [xv]

Gorbachev later called the rowdy parade marchers “rabble” and accused them of plotting to storm the Kremlin. Over the years, his enthusiasm for openness had turned to caustic bitterness in the face of the criticism that free speech enabled. But no crackdown followed the May Day confrontation, not even on the journalists he increasingly blamed for promoting dissent.

Instead it was hardliners in the party leadership who finally took drastic action. In August 1991 they put Gorbachev under house arrest, declared a state of emergency, banned most newspapers and deployed the military to key points in Moscow, including the vast state broadcasting complex.

The coup attempt threatened a frightening return to the past, but it collapsed in three days, done in by resistance from the charismatic former Communist Boris Yeltsin and other political liberals; from a public grown accustomed to freedom of speech; and from journalists who defied the censorship attempts of the coup leaders by printing underground papers and sneaking a daring story about the resistance onto Vremya, the main TV news. Gorbachev was restored to power, but at the end of 1991 he resigned, dissolving the Soviet Union and freeing Russia and the 14 other Soviet republics to move forward as independent countries.

CHAPTER 2: THE 90s

The golden era

Near the end of the Soviet period, party leaders had finally given the concept of glasnost some crucial clarity. A new press law passed in mid-1990 ended the party’s monopoly on media ownership; going forward, anyone 18 or older could register a newspaper or TV or radio channel, at least in theory. By the time of the coup attempt one year later, a handful of new, truly independent news outlets had been created. Chief among them was Ekho Moskvy, a Moscow radio station that managed to broadcast throughout the tense hours of the coup, and Nezavisimaya Gazeta (literally, Independent Newspaper).

Nezavisimaya was only a few months old, but its energetic young staff had already built a solid reputation with investigative reporting and a direct writing style that was a refreshing break from turgid, Soviet-era news prose. The paper’s independence was on dramatic display at a press conference called by the coup leaders just hours after their takeover in August 1991. “Tell me please,” asked Nezavisimaya reporter Tatiana Malkina when she was recognized, “do you understand that this evening you carried out a state coup?”

Malkina’s speaking-truth-to-power question aired live on TV across the Soviet Union and came to symbolize the new journalism that emerged in the glasnost era. Journalists “were messiahs during glasnost,” said Natalia Rostova. “They were the only people who could tell the whole truth.” [xvi]

In the post-coup euphoria, many young people flocked to join the profession. Having no previous experience could be a plus for getting hired; editors were eager to train newcomers who had not worked in the heavily censored world of Soviet media.

By the time the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991, media in newly independent Russia had assumed a role as trusted Fourth Estate, helping shape public opinion and public policy. ”It wasn’t a First Amendment paradise,” said journalist Konstantin Eggert, who worked at some of the early independent Russian media houses. “But it was a time when journalism was developing fast and where the idea that media freedom was important was fairly well received by society – and, by the way, by the political class.” [xvii]

This “golden era,” as many media analysts have labeled it, turned out to be quite brief. By the mid-1990s Russian journalism was in the early stages of what would be a very long decline.

The market arrives

“Under the Soviet system, a journalist and what he wrote was fully controlled by the Communist Party, which funded and hence controlled all publications, television and radio networks across the country,” wrote journalist Anna Arutunyan. Party censorship died with communist rule, but so did the subsidies that paid the media’s bills. What was left, said Arutunyan, was “a media system that completely lacked one of its most important components – an economic infrastructure.” [xviii]

Boris Yeltsin was now president of Russia, and the economic infrastructure his government was about to impose on journalism – and the rest of the country – was a free market. Many journalists were eager to embrace it. “[A] market economy seemed a guarantee of prosperity for all and wealth for the most talented; freedom seemed the opportunity to criticise Stalin without being punished, and to read Playboy,” wrote journalist Nadezhda Azhgikhina, who worked for glasnost leader Ogonyok and later at Nezavisimaya Gazeta.“That is how many serious, literate people understood it, including editors-in-chief and progressive journalists.” [xix]

Azhgikhina and her colleagues at Ogonyok went to court to sue for an end to party control of the magazine and its finances. When they won, “we seriously supposed that independence would bring economic well-being to the magazine,” she wrote. [xx]

Instead, independence brought unexpected financial burdens to editors with little business experience and no notion of how to navigate the economic chaos of Russia in the 90s. The editor of an independent paper in the city of Nizhny Novgorod told academic Natalia Roudakova what it was like to cope with the harrowing hyperinflation of the early 1990s:

“Every month I was getting telegrams that would categorically inform me that the cost of paper is going up by 200 percent this month, or that the cost of ink or whatever is going up 100 percent next month, or that our rent will increase five times, and so on. I had to hustle unbelievably. Once we had no money left to pay for the print-run – so I went to the director of the printing plant and told him, ‘Take some of our shares!’ And he did, so we did not pay for print for the next eight months, and I was instead able to pay journalists their salaries.” [xxi]

Many weeks, though, in many newsrooms, Russian editors had no money to pay their journalists. Some sought temporary solvency by accepting Kremlin subsidies, making their newsrooms potentially vulnerable to political influence from Yeltsin’s government. Unpaid reporters took on second jobs or wrote zakazukha (to order), meaning they accepted cash from businesses or politicians to publish “articles” that were little more than promotional ads for the business – or smears of the politician’s opponents. The prize of independence was being compromised by the need for cash.

Selling positive or negative news coverage to political candidates became an important income source for cash-strapped media in Nizhny Novgorod’s 1994 mayoral elections, according to academic Roudakova. “For the city’s newly minted publishers and broadcasters, who were desperate to make ends meet in the absence of commercial advertising, the campaign was a golden opportunity,” Roudakova wrote. The same editor who had once bargained shares in his paper for access to printing presses now told reporters that he wouldn’t force them to write anything about a candidate. “[B]ut if any of them had anything positive to say” about the editor’s candidate (or negative about his opponents), “they were free to put their talents to use, in exchange for some extra pay.” [xxii]

The rise of NTV

Russia in the 1990s gave journalists plenty to investigate: rampant official corruption, the rise of Mafia-like turf wars, and years of economic turmoil that engulfed the entire country and impoverished pensioners and other vulnerable populations. Despite the severe economic pressures and the ethical compromises some made to stay afloat, national and local newsrooms still delivered a steady flow of serious journalism.

Some of the most critical reporting documented abuses by the Russian military forces that Yeltsin deployed in 1994 to quell a separatist rebellion in the southern region of Chechnya. The war was covered extensively in print and broadcast, but the most powerful reporting came from NTV, a brand-new independent TV channel bankrolled by businessman Vladimir Gusinsky.

Gusinsky, one of Russia’s first oligarchs, had parlayed the country’s growing economic freedom and his own political connections into a successful business empire, including media holdings. The promise of greater political freedom and higher salaries helped him lure some of the best state TV journalists to NTV, where there were generous budgets for big stories like the war in Chechnya. NTV’s graphic images of fighting, its coverage of human rights abuses, and its journalistic rebuttals of the Kremlin’s victory claims in Chechnya drew huge audiences. Public opinion, which had turned against Yeltsin during the chaotic lurch into market reforms, plunged even further.

Then, after months of relentless criticism of Yeltsin and his war, NTV did a political about face as the president prepared to run for re-election.

I returned to Russia a few weeks before that 1996 election, the first time I had reported there since the Soviet collapse. Anne Garrels, then NPR’s Moscow bureau chief, became my tutor on the very changed political landscape we were covering. The fervor that had united “democrats” I’d covered in the glasnost era was gone now. After helping dismantle the Soviet Union and boosting Boris Yeltsin into power as Russia’s leader, some had left the country (a few of them, to escape bribery charges) while others had split into squabbling factions, divided on whether to support Yeltsin’s reelection or one of his rivals. “Scumbag and crook are among the milder epithets” they used for one another, I noted in a “where are they now?” story. [xxiii]

In some ways, the 1996 election looked like a celebration of democracy. Voters had 10 candidates to choose from – including Gorbachev, who got less than 1 percent of the vote. But only two names mattered: Communist Gennady Zyuganov, who represented a return to some version of the past (welcomed by some, feared by many) and the once-revered Yeltsin, now an ailing leader who’d endured a 1993 coup attempt and grown increasingly autocratic, isolated, and unpopular.

Yeltsin looked in danger of losing to his Communist rival, an outcome unthinkable to prosperous business elites like Gusinsky, and to journalists and others who treasured the new freedoms that came with the end of communism. To help assure the president’s reelection, NTV (along with other newsrooms) dropped its harsh criticism of the president. And the channel’s chief news director joined the Yeltsin campaign team – while remaining in his job at privately-owned NTV.

Yeltsin, the vigorous hero of 1991, had become a stumbling, puffy faced, out-of-touch president who looked like “a living corpse.” [xxiv] Now, as election day drew near, streams of upbeat TV images rejuvenated him. He danced at campaign rallies. He signed a truce with Chechen leaders. His office produced a flurry of presidential decrees, including grants of new economic aid to teachers, miners and other workers. [xxv]

Communist leader Zyuganov and his policies got heavy scrutiny from journalists, but the many shortcomings of Yeltsin’s presidential tenure were glossed over. So was his alcohol problem, as well as his disappearance from public sight for several days before the final vote, supposedly due to a sore throat. The heavily skewed coverage undoubtedly helped Yeltsin win by a big margin in the presidential runoff, to the relief – if not exactly the joy – of many Russians, including journalists.

But in their zealous, partisan efforts on behalf of Yeltsin’s campaign, journalists had committed an enormous ethical breach that left public trust in media “forever compromised,” wrote Anna Arutunyan. [xxvi]

Western roles

After the election, a group of American political consultants gave an exclusive story to Time magazine claiming much of the credit for Yeltsin’s victory (the consultants did have input in the campaign, but how important it was is disputed). [xxvii]

Whether the consultants’ work was critical or not, it was not unusual to find Americans doing democracy-building work in Russia in the 1990s. That included programs to develop independent media; the U.S. and Europe spent hundreds of millions of dollars on media development in post-Soviet Russia and Eastern Europe. Even after Vladimir Putin became president in 2000, western-funded projects to foster independent media continued in Russia for several years, until the Kremlin intensified efforts to block them, on grounds that they were “foreign interference.”

Seminars on ethics, investigative reporting, and other topics were popular, though the foreign journalists leading those sessions sometimes met unexpected resistance. Many of the independent newsrooms of the early 1990s “were formed in opposition to Soviet power,” said Michele Berdy, an editor at the English-language Moscow Times. “It was very difficult for them to make the transition” from taking sides to remaining politically neutral, said Berdy, who led training sessions in the 1990s for the U.S. nonprofit Internews. [xxviii]

Once, at the end of a seminar on how media could foster healthy elections by organizing nonpartisan candidate debates, Berdy asked her journalist audience in the city of Yekaterinburg if they thought their media outlets would follow up. “Of course not!” they told her. Their explanation: a nonpartisan debate would have to include the Communist Party, whose leaders “are very skilled because they’ve been doing this for a long time. What if we had a debate and they won it?!” [xxix]

Media development also meant helping independent newsrooms find sustainable business models so they could abandon unethical practices like zakazukha. But the financial challenges remained daunting. Advertising and marketing were new concepts, and support businesses – such as printing and distribution – were often local monopolies controlled or influenced by politicians who deliberately kept prices high.

“Very few local mayors or governors would meet with me,” said American journalist Rob Coalson, who worked in Internews media development programs in the 1990s. And even when local officials did agree to discuss problems facing local media, “none said, ‘Yes, I want a free press and a thriving civil society in my town’.” [xxx]

As newsrooms continued to struggle for financial stability, a devasting ruble devaluation in 1998 brought a fresh round of economic woe. Surprisingly, some eager buyers came to the rescue of failing newsrooms – though not because they cared about good journalism or a free press.

The buyers were businessmen who had watched Gusinsky and NTV revive Yeltsin’s 1996 reelection effort. “They saw political power flow out of a TV camera,” said Internews founder David Hoffman, and they hoped that by buying a local TV station or newspaper, they, too, could become political kingmakers. [xxxi]

By the end of the 1990s, much of Russian media had seen “a return to the authoritarian model of journalism,” said Anna Aruntunyan. The main difference was this: “Journalists now answered to businessmen rather than the Communist Party.” [xxxii]

CHAPTER 3: THE PUTIN ERA

New challenges

In the late 1990s I joined the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) as executive director. The CPJ staff had deep expertise in press freedom issues in every part of the world. I mainly brought knowledge of the former Soviet Union and rosy, outdated memories of glasnost. None of that prepared me for being a press freedom advocate in the challenging new world of post-Soviet journalism.

The most brutal challenge was the growing violence against journalists. Physical assaults and murders – almost unheard-of in the Soviet era – were chilling new risks for those who would pursue reporting on sensitive topics such as corruption and organized crime. Among the most vulnerable were journalists working far from Moscow, like the idealistic young founders of an independent newspaper in the auto manufacturing city of Togliatti.

The collapse of the Soviet Union set off a fierce fight for control of Togliatti’s auto enterprises. Gang violence and official corruption ran unchecked – but not unreported, thanks to Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye, a paper founded in 1996. Death threats, libel suits, and frequent interrogations by police failed to intimidate the two muckraking editor-founders. But after a particularly explosive series of exposés connecting official corruption to the city’s criminal gangs, editor-in-chief Valery Ivanov was killed in 2002 in what appeared to be a contract hit. No prosecutions followed, and 18 months later, co-editor Aleksei Sidorov, who had continued the paper’s aggressive reporting, was also dead.

After Sidorov’s murder, I went to Togliatti with my CPJ colleague Alex Lupis, who led our advocacy program for Russia. It was a dispiriting mission. The paper continued to publish, but the newsroom’s deputy editor, Rimma Mikhareva, reflected the subdued atmosphere. “In the West, it’s established that a citizen has a right to know, and journalists have a right to have access to important information and to give it to the public,” she told us. “I don’t think this concept exists in Russia.”

We also met local officials, including the chief investigator for Sidorov’s murder. Local media and Sidorov’s family had provided compelling evidence that he was killed for continuing the paper’s investigative work. But the chief investigator insisted it was just a street crime, committed by a “hooligan” who approached the editor to demand some vodka. When Sidorov rebuffed him, the man flew into a rage, pulled out an ice pick, stabbed him in the chest, and left him to bleed to death on the street.

Or so the police claimed. Four months after our visit, a local judge acquitted the “hooligan” and called the case that prosecutors had tried to make against him “untenable.” [xxxiii]

Nearly all of the 38 cases of Russian journalists murdered since 1993 have ended in similar stories of justice denied. Two-thirds of those murders were committed since Vladimir Putin took office, and only one has been fully solved (these numbers do not include journalists killed in crossfire or on other dangerous assignments in Russia). [xxxiv] The international outcries that followed the murders of Forbes Russia editor Paul Klebnikov in 2004 and Novaya Gazeta reporter Anna Politkovskaya in 2006 may have helped push authorities to make lower-level arrests, but the masterminds who ordered those hits remain unidentified.

No evidence connects the Kremlin to any of these killings. But the failure to solve the murders is “the product of a criminal justice system beset by corruption, lack of accountability, and conflicts of interest,” said another CPJ colleague, Nina Ognianova, in 2011. [xxxv]

Ognianova went to Togliatti on a second CPJ mission seven years after I’d visited. The murders of the two editors remained unsolved, and the once-muckraking newspaper had become “a shadow of what it once was,” she said.

Gutting the paper’s investigative zeal apparently wasn’t enough for its enemies, though. Years after both editors were murdered, police raided the newsroom, carting away computers and hard drives that contained all of the archives from the paper’s heyday. Police claimed they were looking for unlicensed Microsoft software, but three years later, the computers had not been returned.

Rise of the Kremlin

While the justice system has neglected the murder cases, other parts of the Russian bureaucracy have worked overtime, using a variety of levers to stifle independent journalism. That process began almost as soon as Boris Yeltsin resigned the Russian presidency on New Year’s Eve 1999, bequeathing the job to Vladimir Putin, a former KGB agent who had served in several administration jobs, including a brief stint as prime minister.

Less than three months after the handover, CPJ warned “there are ominous signs that independent journalism faces a bleak future under the Putin regime.” Weeks later the “signs” had become very concrete action, when “tax police” raided Vladimir Gusinsky’s Media-Most, the company that controlled NTV and several other prominent national media outlets.

The tax men carried machine guns and hid their faces behind black balaclavas that made them look more like a SWAT team than accounting monitors. TV and photojournalists captured their ostentatious raid, in images so stunning that we used them frequently to illustrate CPJ updates on the yearlong struggle over control of Media-Most newsrooms.

Weeks after the tax raid, Gusinsky was arrested and offered “a deal straight out of a bad Mafia movie:” hand over your company to Gazprom, the state’s natural gas monopoly, and you can go free. [xxxvi] Gusinsky took the deal and fled Russia.

Left behind were his journalists. Those at NTV waged a very public fight to maintain their independence, including frequent on-air reports about Kremlin and Gazprom machinations. Ultimately, though, they were strongarmed out of the studios. In short order, the Gusinsky newspaper Segodnya was shuttered, and the staff of his newsweekly Itogi “came to work to find we were locked out, and there was a new staff in the building making a magazine,” recalled journalist Masha Gessen. “It took Putin a little less than a year” to complete the takeover of Media-Most, said Gessen. [xxxvii]

That’s about how long it took CPJ to pronounce Putin one of the world’s 10 Worst Enemies of the Press, a classic form of “name and shame” advocacy that always got plenty of media attention. The 2001 “enemies” list – which also included Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei and Jiang Zemin of China – noted that Putin’s Kremlin had “imposed censorship in Chechnya, orchestrated legal harassment against private media outlets, and granted sweeping powers of surveillance to the security services.” The takeover of Media-Most was “ominous and dramatic,” and though new owner Gazprom insisted it was strictly business, “the main beneficiary was Putin himself,” we noted. The journalists in Media-Most newsrooms had done some of the country’s sharpest watchdog reporting, and now their platforms were silenced. [xxxviii]

The country’s other major media baron, Boris Berezovsky, was the Kremlin’s next target. Once the Kremlin accomplished his exile and a takeover of his private TV channel, ORT, other oligarchs with media holdings got the message: fall in line or risk a similar fate.

And fall in line they did. In 2004, for example, when journalists at the newspaper Izvestia challenged official accounts of a hostage massacre in the city of Beslan, Kremlin complaints led to the swift firing of Izvestia’s chief editor. The paper’s then-owner was “metals magnate” Vladimir Potanin, who built his vast fortune from the shady 1990s privatization of state natural resources.

The Putin-era media control system bears a resemblance to the Communist Party structure that kept Soviet journalists in line, with some significant differences. Print and online media with relatively small audiences appear to have more leeway, and a handful of longtime independent newsrooms still survive under Putin, though their journalistic lives can be precarious. Many analysts theorize that Putin allows this so he can tell critics Russia does have independent media. But there’s not much evidence that he cares what press freedom critics have to say.

Enforcement is also carried out differently from the Soviet era. Instead of the prior censorship done by the Soviet agency Glavlit, today’s system pressures journalists to self-censor, in order to avoid stories that might displease authorities or cast them in a bad light. The pressure is often applied through surrogates. These include media owners; tax auditors or other bureaucrats whose newsroom raids can signal a Kremlin warning; and the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media, better known as Roskomnadzor, or “the federal censor” for its enforcement of an increasing number of Putin-era anti-press laws.

The Kremlin can enlist advertisers and other businesses as surrogates, too. In a high-profile example in 2014, independent channel Dozhd (TV Rain) suddenly lost its office lease and found itself dropped from every major cable TV service after it ran an online survey that critics said challenged the Putin era’s version of Soviet greatness in World War 2. The cancellations were widely viewed as Kremlin-inspired retaliation for TV Rain’s independent-minded reporting on many subjects. They came just days before the opening of the Sochi Olympics, a time when “the Kremlin may not want to be seen as closing the only privately owned channel in Russia that pursues a nongovernmental editorial line,” wrote journalist Masha Lipman. “It is much more convenient to have the channel squelched by a cable operator.” [xxxix]

New waves of pressure on media come after Putin’s Kremlin faces a major crisis – such as the large anti-government protests in Moscow in 2011-12, or the international condemnation that followed Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. In a common scenario, top editors whose newsrooms report critically are forced out by Kremlin-friendly media owners and replaced with someone who will take a loyalist line – or at least will avoid sharp criticism of Kremlin policies.

The surrogate system creates a web of pressure points that can be used to keep a newsroom in line. “Everybody tries to be on the safe side,” and thus self-censors, said journalist Sergei Parkhomenko. “Everybody knows what can happen with some people who try to be supporters of independent press.” [xl]

CHAPTER 4: ‘HALF-FULL GLASNOST’

New stirrings

In 2011, as the 20th anniversary of the failed coup against Gorbachev approached, I was teaching journalism at Columbia University. As my students and I watched the uprising in Egypt’s Tahrir Square that spring, I told them how Boris Yeltsin had marshalled resistance to the 1991 Soviet coup using fax machines, just as Egyptian activists were now organizing with Facebook and Twitter. We talked about the courage journalists had shown in standing up to the hardline Soviet coup leaders, a shining example of media’s crucial role in democracy. I used the anniversary to revisit those events for Columbia Journalism Review.

“Twenty years ago, on the evening of August 19, 1991, some of the most brazen and important acts of modern-day journalism played out on TV screens across the Soviet Union,” I began. [xli]

After a brief wallow in glasnost nostalgia, my story pointed out that “What happened later was a really long story,” as a friend who’d worked for NTV in its glory days put it. “And the ending is not a happy ending yet,” he said.

That “really long story” was still unfolding in the early spring of 2020, with fresh attacks on media. The state oil company Rosneft was seeking to tame the country’s two most important business media outlets – by filing a $600 million libel suit against one and maneuvering a possible takeover of the other. Bureaucrats were using a newly enacted ban on “fake news” about COVID-19 to target Novaya Gazeta, a leading investigative paper since the 1990s, for its reporting on abysmal pandemic conditions in Chechnya. And Russian officials attacked COVID-related reporting by foreign correspondents, demanding retractions or apologies from The New York Times, The Financial Times, and Bloomberg.

All of those actions came as Russia headed toward a historic vote on constitutional amendments that could potentially keep Vladimir Putin in power until 2036. During his first 20 years in office, many journalists had left the profession or even the country, some to escape censorship, others to flee death threats. With the prospect that Putin could get a lengthy term extension, an old question arose anew: Who would want to become a journalist in today’s Russia?

And yet there were still reporters and editors determined to keep independent news alive, some in newsrooms as beleaguered as the business paper Vedomosti, one of state oil company Rosneft’s targets, or the scrappy Novaya Gazeta, which had survived the murders of five of its journalists and near-constant official pressures throughout its 27-year history.

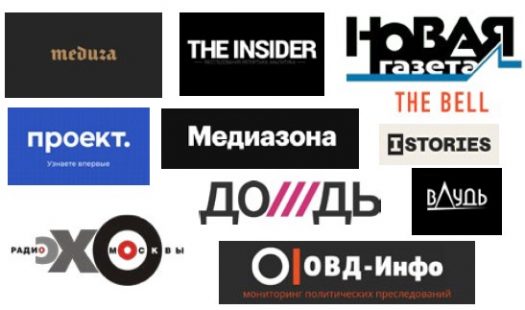

But the survival of a few longtime stalwarts offered scant inspiration, given the constant pressures they continue to endure. What’s given new hope for independent journalism is the appearance in the past several years of startups – all of them owing their existence to the Internet – that are reviving investigative reporting and testing business models that insulate them from some Kremlin pressures.

Several Russian journalists have sought to name this trend: the new wave, Media 3.0, or digital samizdat, the latter referring to the underground publishing system used by Soviet dissidents.

A particularly optimistic label came from Russian journalist Maxim Trudolyubov, who wrote in 2019 about “Russia’s Half-Full Glasnost.” Trudolyubov described “an unmistakable sense of an increasingly vibrant journalistic scene in Russia,” while adding caveats that the new ventures were small and had yet to prove they could be financially sustainable. [xlii]

Emerging platforms

This “vibrant journalistic scene” includes one-person Telegram blogs, a few of which have significant loyal followings, as well as YouTube channels that pursue investigative journalism or thoughtful talk and analysis. Some of the journalists on YouTube draw large audiences, particularly among the younger populations who tell pollsters they don’t watch state TV.

“Russian YouTube is becoming very important,” said investigative journalist Yevgenia Albats, editor-in-chief of the independent site Novoye Vremya (New Times). “It is a sort of substitute for Russian TV.” [xliii]

Perhaps best-known on YouTube are the deeply reported, slickly produced documentaries from opposition figure Alexei Navalny, which routinely get a few million views (sometimes a few tens of millions). While Navalny’s documentaries are designed to push his anti-Kremlin political message, they are also widely regarded as some of the best journalistic investigations on business and political corruption in Russia. [xliv]

Yuri Dud (pronounced “dude”), a young sports journalist turned YouTube interviewer, draws enthusiastic audiences for his interviews with guests who have edgy views and are banned from state TV – such as Navalny. Dud’s most popular videos are the several documentaries he’s done over the last year. Two of them explore topics that were first exposed during glasnost in the 1980s but were later buried, to a large degree, in the Putin era. “Kolyma — birthplace of our fear” [xlv] examines the horrors of Josef Stalin’s Arctic labor camps and has recorded more than 21 million views. “HIV: the epidemic no one wants to talk about,” had nearly 12 million views in the first week after it was posted on Dud’s channel.

The HIV program [xlvi] spoke frankly about an issue shrouded in shame and secrecy in Russia, targeting in particular the young audiences that follow Dud. “Now they know that they should use condoms and that they should go and do testing,” said Albats. “He’s doing excellent, absolutely excellent, stuff.” [xlvii]

Modeling new businesses

YouTube, popular in Russia, gives Navalny (3.7 million subscribers) and Dud (7.6 million) very high profiles. Other players in this new journalism scene are also digital natives, but their sites have far more modest audiences. They are gaining attention, though (traffic for most doubled during the early months of the pandemic), and so are the innovations they’re using to protect themselves from Kremlin meddling.

Foreign registration is one innovation. Three sites, Meduza, The Insider, and Vazhnie Istorii (Important Stories, or istories for short) have their business bases in Latvia, a former Soviet republic with a strong press freedom record, while news sites The Bell and Proekt are registered in the U.S.

Others, such as Moscow-based digital native Mediazona, a nonprofit supported mainly by its subscribers, are also strategizing to guard their independence while being formally registered inside Russia.

Regardless of where they are registered, all share the goal of shielding their journalism from the Kremlin influence that hangs over most Russian newsrooms today. Many at these startups worked in those newsrooms, before leaving or being pushed out by political pressures or Kremlin-inspired takeovers.

The best-known case is Meduza, founded in 2014 after Galina Timchenko, editor in chief of the popular news site lenta.ru, was fired by its oligarch owner over coverage of Russia’s incursion into Ukraine. Other lenta.ru colleagues quit and followed Timchenko to Latvia, where Meduza’s administrative and editorial staff oversees the work of reporters inside Russia.

Foreign registration puts Meduza and the other sites beyond the reach of Russian bureaucrats. “The tax man can’t knock on our door and ask questions,” said Meduza editor-in-chief Ivan Kolpakov. [xlviii]

It also enables them to raise money from foreign investors and foundations without having to publicly brand themselves as “foreign agents,” as Russian-registered media are required by law to do if they receive non-Russian money. Still, Meduza and others decline to name their investors. “Finances, this is crucial information for Russian propaganda,” said Kolpakov. “Propaganda uses it a lot to show you are not pro-Russia.” [xlix]

The newest Latvia-based site, launched in late April 2020, is istories. Devoted to investigative reporting and collaborations with other newsrooms, istories has finance and fundraising staff in Latvia. Co-founder Roman Anin and others on the investigative team are based in Moscow, but no documents are kept in the Moscow office, so “there is nothing to raid,” Anin said. Nor can Russia block the site’s bank accounts “as they do with Navalny’s team, because we don’t have any accounts” in Russia, Anin said. “They can’t make some fake payments to our accounts to claim we are foreign agents, because again we don’t have accounts.” [l]

Precautions like these make istories and the other foreign-registered sites “difficult targets” for the Kremlin, said Anin.

Difficult, but not target-proof. In 2019, NTV (owned by the Kremlin-loyal energy monopoly Gazprom) produced a propaganda show that blasted Anin and two other startup founders, Roman Badanin of the investigative site Proekt and Elizaveta Osetinskaya of The Bell, which covers Russian business and politics. All three had done fellowships at Stanford University in recent years, a journalistic honor that NTV turned into sinister evidence of foreign influence. At one point in his breathless presentation, the narrator says “Many experts are convinced that Proekt is an attempt by the CIA to meddle in the affairs of Russia.” None of the alleged experts are named, nor is evidence presented that supports the “spy” claims against the journalists. [li]

In 2019, Moscow police used a different smear tactic to go after foreign-registered Meduza, through its Moscow-based investigative reporter Ivan Golunov. Police planted fabricated evidence on Golunov when they arrested him on drug charges. The ham-handed but chilling action sparked a huge public outcry from many Russian newsrooms — independent, and not-so independent. Authorities were forced to release Golunov and drop the charges against him, in an outcome that was celebrated by journalists.

Few saw it as a breakthrough moment, though – not for press freedom, or for the justice system, which investigative reporters say entraps many Russians who end up in prison on false drug charges. “We understand that at every moment they can invent something against us,” said Mediazona reporter Yegor Skovoroda. [lii]

Because it’s registered in Russia, six-year-old Mediazona is more vulnerable to traditional government pressures than foreign-based sites like Meduza. “We of course have some difficulties with Roskomnadzor,” said Skovoroda, referring to the agency that issues broadcast licenses and registers Mediazona and other news outlets based in Russia. The agency also enforces laws such as Russia’s COVID-19 “fake news” ban, issuing warnings or fines. Failure to comply could lead to blocked access, meaning anyone in Russia who wants to reach the site would need a workaround, such as a Virtual Private Network, or VPN.

As a result, “We usually do what they [Roskomnadzor] want,” said Skovoroda. “But we try to do it in such a way that it’s obvious for our readers what happened.” [liii]

For example, when Roskomnadzor ordered the site to remove a link to one of Navalny’s juicier corruption investigations, Mediazona told readers it was acting on orders of the censor. It then gave the name of the Navalny video (“Yachts, oligarchs, girls”) and said it had already been viewed by 2.5 million people, signaling the audience that it was a story worth tracking down.

Covering COVID

Public opinion polls show that although the TV audience is shrinking – dramatically so among younger generations – 73 percent of Russians still say they tune in to broadcast news. As the pandemic grew globally in February and March, those who only watched TV may have seen little reason for concern about COVID-19. In a typically upbeat message on March 3, an official told Channel 1 viewers that Russia’s situation was “terrific – we’ve been living for almost three months along a huge border with China and have only five cases, so all the measures we’re taking are clearly effective.”

As for where COVID-19 came from, Channel 1’s nightly Vremya program offered a February 5 roundup of conspiracy theories: the virus originated in a Chinese bioweapons lab; or it was developed by American pharmaceutical companies “that simply wanted to make money;” or it was manmade to target only Asian populations. Anchor Kirill Kleimenov stopped short of endorsing any of these theories but concluded: “Even experts who are cautious in their assessments say that nothing can be ruled out.” [liv]

TV’s tone began to shift from peddling conspiracies and dismissing dangers when Vladimir Putin emerged from weeks of silence in late March to acknowledge the pandemic’s spread. Images of him holding a video conference with regional governors and visiting a hospital in hazmat gear sent a new message: the virus is here, it’s serious, but the president is in charge and decisively facing down the health threat.

A review of nightly news programs on Channel 1, Rossiya 1, and NTV throughout the week of April 6-10. 2020, showed that once the Kremlin began to address COVID publicly, the pandemic pushed aside almost all other news. Anchors urged viewers to isolate and take sanitary precautions, underscoring the point at times with stark images (a traffic jam of ambulances at a Moscow hospital) and stark language (“If you want to live, stay at home,” warned Kleimenov, the Channel 1 Vremya anchor, on April 10). [lv]

But the overall message remained upbeat. Video clips showed new hospitals being built at a feverish pace, and interior shots of existing facilities revealed plenty of beds surrounded by up-to-date-equipment. The medical workers in these scenes had ample supplies of protective gear.

To hammer home the message that Russia was well prepared (unlike western democracies), TV news showed dire scenes from the U.S. and Europe: mass graves, overloaded hospital wards, medical workers wearing improvised protections, and crowded lines of the unemployed. Things were so bad in Italy, TV reported, that Russia had sent some of its doctors there to help out, while a planeload of medical equipment was sent as aid to the U.S. (The plane’s supplies included a brand of ventilators that later caused explosions and fires in Russian hospitals. Though the machines hadn’t been used in the U.S., American officials said they were sending them back to Russia “out of an abundance of caution.”)

For the Russian audience, these early April newscasts gave an impression of little to worry about at home, unless you were shopping for lemons, garlic, or ginger. Prices for all three soared, thanks to Internet stories touting them as COVID-19 home remedies.

Alternative news

In addition to monitoring the main news programs on state-controlled TV in early April, this study examined reporting by other media over two months, beginning in late March and ending as Russian regions started to ease self-isolation restrictions.

The initial goal was to monitor several of the best-known independent outlets created in the past few years, all of them either described earlier in this report or in the appendix: The Bell, The Insider, Mediazona, Meduza, OVD-Info and Proekt. (Yuri Dud and Alexei Navalny did not post new YouTube documentaries on COVID issues during the study period. Navalny did use his live blog and social media to critique government policies and amplify COVID reporting done by Meduza, The Insider, and other independent sites.)

As we monitored the selected sites, while keeping an eye on other coverage, two things became apparent. First, some important early warnings about the pandemic came initially on social media, posted by health workers or others. Some of these whistleblowers suffered reprisals at work or threats from local officials, a reminder that journalists are not the only targets of free speech repression in Russia.

Also, the outlets we followed most closely were not the only alternatives to Russian TV’s censored reporting. In particular, two older independent newsrooms did some of the best reporting in this period – Novaya Gazeta, especially its longer features and investigations, and TV Rain’s COVID fact-checking videos. Moscow Times, an English-language paper (now only online) founded in 1992, provided detailed coverage for its ex-pat audience; during the COVID crisis, it translated content into Russian, too. Some once-independent outlets, tamed over the years by Kremlin pressure — such as the three business news outlets Kommersant, Vedomosti, and RBC – still produced much useful reporting for their audiences. Vital independent reporting was also available from international outlets, such as BBCs Russian Service, and from local bloggers and news portals in a number of Russian cities.

The role that all of these media played in defining Russia’s response to the pandemic deserves a systematic study over a longer period. What was clear from our work, which monitored COVID coverage in real time, was this: there were multiple outlets and many journalists in Russia presenting constant reality checks on the pandemic and its many repercussions.

While TV news in early April was offering reassuring images of Russian health care’s readiness, for example, Mediazona reporter Sasha Bogino was filing devastating daily updates from her hospital bed in St Petersburg’s War Veterans Hospital, where she was admitted with COVID-19 symptoms.

Bogino’s hospital diary described overworked and underprotected hospital staff, as well as major sanitary lapses (cockroaches were a recurring theme in her text and photos). Patient information was hard to come by; “pneumonia” was her official diagnosis, but Bogino was tested four times for COVID and never learned all of the results. Near the end of her stay she confided to a hospital therapist that she was scared and just wanted to go home. “I don’t know how I will physically and psychologically recover from the hospital,” she wrote. “The therapist tells me that she’ll recommend antidepressants when I’m discharged.” [lvi]

Readers who followed Bogino’s installments sent her messages saying she’d given them strong motivation to isolate at home, lest they catch the virus and endure similarly grim encounters with Russian health care.

By the time Sasha Bogino went to the hospital, a wave of pandemic information had begun flooding Russian social media, blogs, and independent news sites, much of it contradicting TV’s upbeat reports. An early example: a March data analysis by investigative site Proekt used government statistics and models developed by European researchers to forecast severe shortages of ventilators and intensive care unit beds if Russia took no quarantine measures. [lvii]

Anecdotal reports of shortages came from local bloggers and medical workers, who complained on social media that they lacked masks, gloves, and other protective equipment. Independent media amplified these local messages by casting a reporting net across the country.

Meduza, for example, “researched our own platforms, our own Facebook, our own VKontakte [a Russian social media platform] accounts” to identify and reach out to doctors across Russia, said editor Kolpakov. And on March 26, the day after Putin’s first national address on COVID-19, the site published an invitation to hospital workers to “tell us what is happening at your workplace.”

That crowdsource request yielded more than 500 responses, which Meduza summarized in a March 31 article showing widespread shortages of staff, COVID tests, and protective equipment. A typical response: a nurse in Yekaterinburg told Meduza that management had ordered staff at her hospital to sew their own face masks. The hospital couldn’t provide them because “ ‘We are not China. We have nothing,’ is what the bosses tell me,” the nurse reported. [lviii]

Medical workers became crucial sources for many stories pursued by independent media, including a new weekly podcast launched by Proekt, in which doctors talked in depth about Russia’s overtaxed health care system, misleading COVID-19 statistics, and their personal experiences in fighting the pandemic. Few Russian doctors seemed fazed when Kremlin press secretary Dmitry Peskov fumed that they should take their complaints to local health officials “and not to the media.”

But some health workers did face repercussions — workplace discipline or threats of prosecution — particularly when they posted their own videos or online messages about shortages or dangerous working conditions. The national law banning COVID “fake news,” passed early in the pandemic, also threatened journalists, including those doing groundbreaking reporting for local blogs or news portals in places far from Moscow.

In the oil-and-gas-rich region of Komi, northeast of Moscow, for example, the independent news portal 7X7 found itself under fire when it blew the whistle on a COVID outbreak. 7X7 reported that Komi became an early hot spot after a surgeon with virus symptoms kept working at his hospital. The local health minister ordered an investigation of how the news had leaked, and police called in 7X7’s director for questioning. The reporting had already had an impact, though; before any action proceeded against 7X7, the Kremlin forced both the health minister and the regional governor to resign. [lix]

The official response was very different to another hot spot report, this one by Novaya Gazeta, which described draconian quarantine enforcement in Chechnya. Headlined “Death from coronavirus is the lesser evil,” the story said residents of Chechnya were afraid to report COVID symptoms after the region’s strongman leader Ramzan Kadyrov had equated those who carried the virus with “terrorists” and suggested they could be dealt with violently. Chechen residents also told the paper that entrances to their homes were sealed by authorities to enforce the quarantine. Meanwhile, Kadyrov, his family, staff, and bodyguards traveled everywhere freely – and safely, said Kadyrov, because they were all tested for COVID twice a day. [lx]

“Do they have time in Chechnya to test anyone else except Kadyrov and his entourage?” asked reporter Elena Milashina.

The backlash against Novaya Gazeta was swift. Kadyrov, whose iron-hand rule in Chechnya has Kremlin support, accused the paper of bullying him and branded its journalists “foreign agents.” His message also contained a veiled threat to Milashina, who has reported extensively on Chechnya and human rights violations there. “If you want us to commit a crime and become criminals, just say it. One (of us) will take on this burden, this responsibility,” said Kadyrov.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov called Kadyrov’s statement “quite emotional,” but added, “on the other hand, the current situation is very emotional.” (Soon after, Kadyrov went to Moscow for COVID treatment, according to many Russian press reports; the Chechen leader denied he was sick.)

Many of the pandemic themes covered by Russian independent media would sound familiar to audiences in other countries. News sites warned readers about COVID-related scams, described obstacles in applying for unemployment benefits, and looked at the impact on communities largely ignored in state media, such as those living in orphanages, nursing homes, and prisons.

Independent sites also used their particular expertise to focus on specific issues. The Insider’s “Anti-Fake” fact-checking feature debunked COVID misinformation and conspiracy theories, using the “pants on fire” rating on its “Pravda meter” for some reports in state media. The Bell’s economic analyses put the Kremlin’s financial responses in context: the $42 billion allocated for COVID relief in Russia was about 2.6 percent of the country’s GDP, while the comparable figures were 14 percent in the U.S. and 10 percent, on average, in European countries. And OVD-Info, created to monitor political activism, kept would-be protestors around the country informed about pandemic restrictions on public assembly and offered tips on “ways to contribute to the fight against repression without leaving home.”

In a few cases, government officials were responsive to some of the pandemic reporting by independent sites, revising statistics or following up on problems highlighted in media stories. In other cases, newsrooms were punished, with fines or warnings from Roskomnadzor for allegedly writing “fake news.” But at least in the early weeks, independent newsrooms that exposed pandemic misinformation did not suffer the same level of reprisals imposed in previous crises, such as the 2014 takeover of Crimea. The Kremlin may have seen their COVID reporting as less of a challenge to sensitive policy, or perhaps even helpful in impressing upon people the severity of the public health crisis.

How many deaths?

Perhaps no pandemic issue was scrutinized more than Russia’s official mortality statistics. As world media chronicled COVID’s deadly spread through Europe and the U.S., some compared the numbers in western countries with Russia’s relatively low official death count and asked, “What’s going on?” (ABC News was more explicit about why so many raised the question. “Some say it’s a coverup,” said its headline.). [lxi]

Reporting by Russian independent media explored two explanations – one official, one not. The explanation offered by national health ministry officials noted that Russian procedures, which predated the COVID outbreak, took a very conservative approach to determining “cause of death.” While some countries counted nearly anyone who died and had tested positive for coronavirus as a COVID death, Russia’s guidelines called for autopsies and instructed morgue pathologists to determine whether the primary cause was COVID or another existing condition – such as cancer or kidney failure.

Thus, “if a person has a brain hemorrhage after earlier testing positive for the coronavirus, the cause of death will be classified as the hemorrhage, not Covid-19,” explained The Moscow Times. [lxii]

Russian health officials called this system “objective,” but critics said it badly underplayed COVID’s impact. And some demographers and doctors told journalists that the system was highly vulnerable to political manipulation. “If you have any Russian statistics on mortality from coronavirus, you need to multiply it by an average of three to four,” one demographer told Meduza. [lxiii]

The unofficial explanation, investigated by several outlets, was that in some cities and regions, local officials manipulated reports from the pathologists in order to please their political bosses in Moscow. The Kremlin was particularly eager to see death counts declining in the weeks leading up to its July 1 referendum on constitutional changes; lower rates would encourage higher voter turnout to give Putin the endorsement he needed to stay in office beyond constitutional limits. (When the referendum passed in July, it “zeroed-out” the many years Putin had already served, making him eligible for two more presidential terms that would run until 2036).

While a number of media outlets cited anonymous sources who described pressure to manipulate statistics, the most damning report came from the independent site Znak. It posted an audio recording in which the governor of Lipetsk, a region southeast of Moscow, was heard telling subordinates “Your numbers need to change, otherwise they’ll think badly about our region.” The governor confirmed to Znak that his voice was the one in the recording, but said he was just trying to bring the local statistics “in line with the facts.” [lxiv]

CHAPTER 5: LEGACIES

Chernobyl and glasnost

Russia is far from the only country charged with undercounting its COVID-19 deaths. But the frequent, skeptical coverage of that story in both Russian and international media is clear evidence that today’s Kremlin still bears a legacy of the long-ago Soviet coverup of Chernobyl. It’s a legacy unlikely to be shed without a political shakeup, and no one expects that as long as Putin remains in office – which now could be until 2036.

The pandemic exposed another legacy, though, this one more positive, and that is the endurance of the journalistic ideals first fostered by glasnost.

The journalists at the forefront of today’s independent Russian media are a small band. Many got their start at Novaya Gazeta, or Kommersant, or other newsrooms founded in more optimistic times for press freedom. Compared with the media where they worked in the past, their current staffs are tiny, ranging from a dozen to a few dozen employees. Though traffic to most of their sites grew during the pandemic, those numbers don’t clarify whether new audiences were coming to their reporting or the same people were simply visiting more often.

If there were newcomers, they almost certainly were from younger generations. Surveys by the Levada Center, a polling agency created in the glasnost era, show that 73 percent of Russians still got news from TV in 2020 (down from 94 percent in 2009). But among Russians 18-24 TV news watching has plummeted to just 28 percent, and only 38 percent of those aged 25-34 say they watch TV news. In both of those age categories, a third or more now say they get news from online news sites.

Those numbers confirm that news consumption patterns are changing, “but very slowly,” said Denis Volkov, the Levada Center’s deputy director. “It is a change for the future.” [lxv]

Whether any independent sites will still be around in the future is a big question. Independent media have often been on life support in Russia, particularly in the Putin years, and even before Putin’s victory in the July 2020 constitutional referendum journalists did not rule out stepped-up Kremlin action aimed at silencing their voices.

One action could be a Kremlin move to isolate Russia’s Internet from the rest of the world, a possibility under a “sovereign internet” law approved in 2019, though few think it’s likely to be used — at least not to cut off the entire country. “Of course, it is theoretically possible to turn Russia into North Korea,” Roman Dobrokhotov, founder of The Insider, told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. “But this is a difficult choice.” [lxvi]

Reinforcing that view, say some journalists, was the government’s announcement in the summer of 2020 that it had abandoned efforts to block the encrypted messaging service Telegram. The blocking efforts proved particularly difficult after some Kremlin officials became regular users of Telegram.

“Internet users are fairly quick to learn new techniques and adapt to the changing environment,” the Russian NGO RosKomSvoboda, which advocates for Internet freedom, noted in a 2019 report. That adaptability “in turn stretches to infinity the frontline with law enforcers and makes it increasingly difficult to counter the free flow of information.”

But another ominous possibility arose in the wake of Putin’s July 1 victory in the constitutional referendum. A week later, federal security agents arrested former investigative journalist Ivan Safronov for treason, and some predicted it was the first blow in a new wave of legal harassment. But any fears of a fresh crackdown did not stop independent journalists from swiftly launching public protests and issuing strong newsroom statements casting doubt on the charges.

“[U]ntil the authorities present convincing evidence of Ivan Safronov’s guilt for an open and impartial assessment, we will presume not just his innocence but that the entire case against him is fabricated,” said Meduza’s statement. “The purpose of this case (and many cases like it) is to pressure Russia’s fewer and fewer remaining independent journalists,” Meduza said, adding: “Journalism is not a crime.” [lxvii]

Appendix – Independent Russian News