Executive Summary

The US-European relationship remains a cornerstone of American security and prosperity. It is never in America’s interest to remain a bystander when Europe’s cohesion is under threat. The refugee crisis in Europe is such a threat. This report outlines a strategy for American leadership to help Europe turn this crisis into an opportunity by providing American help in refugee resettlement, aid to the front line states in the Middle East, and co-operation with European allies to secure Europe’s maritime borders and save refugee lives.

This report, prepared by a team from the Harvard Kennedy School for the Richard Holbrooke Forum on Diplomacy at the American Academy in Berlin, builds on the conclusions of a joint meeting with the Brookings Institution on the European Refugee Crisis held in Washington, DC in February 2016. It also supplements an earlier report, by the same team, published by the Shorenstein Center at the Harvard Kennedy School in January 2016.

Background

In March 2016, the EU and Turkey signed a deal designed to improve the management of an increasingly unmanageable refugee flow, reduce lives lost during dangerous sea crossings, and provide support for the millions of refugees living in Turkey.

The deal has encountered criticism from human rights groups who are concerned about the potential for inhumane treatment. These concerns should be taken seriously. As it stands, for example, the deal fails to:

- Provide for refugees needing resettlement after traffic to Greece slows

- Support front line countries sharing the burden (Jordan and Lebanon)

- Address a potential increase in dangerous Libya-Mediterranean traffic

While the deal may have been intended as a policy of rescue, it is vital that it not be transformed over time into an illegal practice of forced return.

Nevertheless, in the context of Balkan countries closing their borders, Greece struggling to provide for refugees trapped in limbo, and an increasingly divided Germany left to shoulder the responsibility, the EU-Turkey deal – as flawed as it is – represents Europe’s best hope for regaining control of the situation.

As the cessation of hostilities unravels in Syria and peace talks in Geneva stall, citizens of Europe can expect no end to the flows of refugees and migrants. Without assistance from the outside, Europe and neighboring allies will continue to be destabilized. The deal should provide the US with both the impetus and the structure within which to honor its transatlantic commitments and provide support to a struggling region.

Key Recommendations

We believe the US should take a leadership role in addressing significant gaps in the deal by:

- Building a coalition for high volume voluntary resettlement to resettle refugees beyond the 1:1 cap in the current deal. A leadership role will only be effective if the US shoulders its share of the burden. The US should commit to screening 65,000 refugees currently in Turkish camps for US resettlement within the year.

- Providing resources for education, employment, and security assistance for refugees in Lebanon and Jordan. Increased financial and political support would acknowledge the burdens other front line countries bear and help ensure their continuing stability.

- Supporting search and rescue in the Mediterranean to prevent migrant drownings on the Africa-Italy route. Restrictions on migration to Greece will likely lead to increasing attempts to use the more dangerous Mediterranean route. The US should offer patrol, reconnaissance, and search and rescue assistance to deter deadly crossings.

Through leadership and assistance in these three areas, America can make the EU-Turkey deal stronger, more forward-thinking, and more humane.

The Context

Last year refugee flows into Europe caused a humanitarian crisis at Europe’s borders, strained the bonds of the European Union, and overwhelmed the capabilities of the states closest to Syria. Previous attempts to handle the situation have been either unsuccessful, as in the EU’s failed attempt to mandate burden-sharing, or unsustainable, as in Germany’s generous but unrepeatable decision to accept more than 1 million refugees last year.

At first, 2016 looked like it would be even worse. Military advances by the Syrian regime created new waves of tens of thousands of refugees. Overcrowded refugee camps in front-line states motivated refugees to push onward to Europe. In January 2016 alone, more refugees arrived by sea in Greece than in the first six months of 2015.

Driven by these worsening conditions, on March 18 EU leaders signed a deal with Turkey to gain control of migrant flows, bring fairness to the resettlement process, and reduce the tragic drownings that captured the world’s attention last year.

The EU-Turkey Deal

Under the terms of the deal, Turkey agrees to take back any migrants who travelled to Greece and were not offered asylum. For each migrant Turkey takes back from Greece, one would be resettled from Turkey into the EU. This 1:1 ratio would reduce the burden on Turkey, along with an additional grant of 3 billion Euros to be spent on refugees. This grant brings total EU spending on refugees to Turkey to 6 billion Euros, which will go towards access to food, shelter, education, and healthcare. Turkey will also benefit from visa liberalization and the renewal of negotiations for EU membership.

Priority for resettlement will be given to the Syrians who have not previously entered or tried to enter the EU irregularly. The EU will also take into account the UN Vulnerability Criteria during the selection process.

The deal was only implemented in full on April 4th, when the first migrants were returned from Greece to Turkey. Nonetheless, some early indicators suggest the deal is working. Migrant arrivals in Greece in the week ending on April 10th were 86% lower from the week before.

Humanitarian Criticism of the EU-Turkey Deal

The EU-Turkey deal has been criticized by humanitarian organizations and by groups advocating for migrant welfare. Specifically, UNHCR’s Europe regional director has argued that “the collective expulsion of foreigners is prohibited under the European Convention of Human Rights.”[1] But the deal as negotiated does not call for collective expulsion. Under the existing deal, the refugees arriving in Greece would be handled individually through an existing legal asylum process with multiple options for appeal.

Upon arrival in Greece, each refugee would be able to submit an asylum claim, which under existing Greek law would be considered “for each individual case and applicant separately.”[2] The Greek government would determine, for each applicant, whether they could be safely returned to Turkey. If this is determined to be true and the applicant’s asylum claim is denied, they can appeal within 15 days and remain in Greece until their appeal is adjudicated. If the applicant is denied their first appeal, they can appeal again to a court.

The real concern about the deal is that chaotic conditions and under-resourced Greek administrative capacity will lead to inconsistent or unfair treatment in practice. For example, UNHCR recently reported that 13 Afghan and Congolese asylum seekers in Greece did not have their claims processed before being returned to Turkey.[3] This appears to be a mistake by overworked staff rather than a malicious act, but shows the risk to the migrants and to the legitimacy of the deal if the EU does not further support Greek efforts to adjudicate asylum claims. As of May 1, the promised frontier and screening personnel, promised to Greece from EU member states, have not yet arrived.

Legal Criticism of the EU-Turkey Deal

There are also concerns about the legality of returning refugees to Turkey. This raises the specter of refoulement, referring to the forced return of refugees to their country of origin. Prohibitions against refoulement are at the core of international refugee law. But the proposed readmission to Turkey is not refoulement. EU legislation allows refugees to be returned to legally designated “safe countries” if doing so will not endanger the refugees.

Some have argued that Turkey is not a safe country for refugees, because of persecution and discrimination. It is true that more could be done for refugees in Turkey, especially in education and labor market access. But refugees experience persecution in many countries, even in Europe, and none of this rises to the level of threat they would experience in their home countries. The “safe country” exception to non-refoulement is a well-established legal norm that fulfills the essential purpose of allowing burden sharing among resettlement countries.

There are valid concerns about the physical safety of refugees in Turkey, because of terrorism and violence spilling over from Syria. The EU should offer assistance in safeguarding refugee populations. But we must not lose perspective. France and Belgium are still safe countries for refugees, despite the terrorist attacks in these countries. We must not allow the actions of a few terrorists to interfere with a policy that could benefit millions of people.

Of more concern are allegations that Turkey has returned Syrians and Afghans to their countries without due process and against their will. Amnesty International has reported hundreds of cases of Turkish authorities deporting refugees, mostly in the chaotic southeastern border region with Syria. Turkey has denied these allegations but they must be investigated by an independent authority. The EU must ensure that Turkish handling of refugees – both Syrians and non-Syrians – is consistent with EU and international law in order to continue readmission to Turkey.

The most important response to these well-meaning criticisms is that the status quo is a moral disaster, and this deal, however flawed, is a chance to improve upon it. Criticisms of Turkey’s refugee services are productive if they can motivate the international community to support them, but are unproductive if they are used to justify inaction in a worsening humanitarian crisis.

Future Risks and US Contributions

America can support the deal currently underway between Europe and Turkey and in doing so can address the concerns of human rights advocates. By building a global coalition of resettlement countries, broadening support to Jordan and Lebanon as well as Turkey, and supporting NATO rescue operations in the Mediterranean, America can make the deal stronger and more humane.

Recommendation One: Build a Coalition for High Volume Voluntary Resettlement

The 1:1 ratio that currently guides readmission and resettlement is unsustainable in the long-term. This ratio means that for every refugee that Turkey takes back from Greece, one will be resettled directly from Turkey to the EU. The goal of the 1:1 ratio was to quickly stop dangerous seaborne migration from Turkey to Greece by removing the incentive to make the risky crossing. Ideally, the 1:1 ratio would relieve the burden on Turkey of accepting refugees returning from Greece – there would be no net increase in Turkey’s population. However, as the EU-Turkey deal becomes successful and fewer migrants must be returned to Turkey, fewer will also be resettled into Europe.

In the long-run, the 1:1 ratio will actually constrict resettlement. This is why the EU-Turkey plan also called for a parallel Voluntary Humanitarian Admission Scheme once irregular immigration was substantially reduced. Still, even as arrivals in Greece are declining, this additional resettlement program is nowhere in sight. The EU has failed to organize a high-volume resettlement program, as it has for the last year.

Without this concurrent resettlement program, refugees in Turkey may perceive that direct EU resettlement prospects are dwindling and be re-energized to pursue dangerous irregular routes by land and sea. To keep migrant flows manageable, migrants have to be convinced that their best option is to remain in Turkey and participate in official programs of resettlement.

The US can contribute by taking a leadership role in organizing a coalition of countries willing to accept refugees – but first it must agree to resettle more refugees on US soil. Once the US has demonstrated its own commitment, it will be better positioned to extract commitments from other countries, especially ones who do not have a record of accepting refugees.

Specifically, the US should rapidly screen 65,000 refugees currently in Turkish camps for resettlement in the US in 2016 and 2017. The current immigration vetting process is mostly paper-based, costly, and slow. The U.S. government physically transfers paper files 6 times over thousands of miles to different processes centers within the U.S. and abroad to Embassies and Consulates. The process takes between 18 and 24 months. While this time frame has been touted as a strong security measure, it is the detail of security and medical checks and not the length of time that make the process secure. The time frame itself is reflective of inefficient administrative processes.

In our previous report—A Plan of Action—we outlined practical ways to allow the US to rapidly resettle 65,000 refugees:

- Streamline Security and Medical Processing. More processing should be done in parallel. For example, medical screening should begin at the same time as security screening so that lengthy medical tests have time to be completed without delaying the process. Medical screening should be contracted out to selected local clinics where the refugees can go directly. This will reduce the burden on U.S. government staff and the backlog of refugees waiting for medical clearance.

- Surge Screening Personnel to Turkey. By consolidating the screening process abroad, the US can avoid transferring documents and lengthy delays. When security, medical, and customs officials are co-located with the populations they are screening, multiple examinations and interviews can be completed on the same day. The Canadian government was able to resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees in four months by sending a few hundred screening personnel abroad.

- Introduce new digital tools to speed up the adjudication process. The US Customs and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of State are currently collaborating on a pilot program, the Modernized Immigrant Visa (MIV) Project, which digitizes the visa application and adjudication process. The MIV project is aimed at improving the visa applicant experience and increasing efficiencies in the adjudication process by digitizing as much of it as possible. A suite of applications, mainly belonging to USCIS and State, can efficiently process and manage electronic immigrant records. The U.S. Digital Service, a team within the federal government that seeks to improve and simplify digital services, can create a cross-agency digital service team to support the implementation of the overall MIV pilot

To build a coalition of resettlement countries, the US should target countries who traditionally have not taken many refugees, including countries in South America, the Gulf, and Muslim-majority countries in South Asia. Every refugee that can be resettled outside of Europe by this US-led coalition makes the deal more palatable both to Europe and Turkey. Most importantly, the deal is more credible to the refugees who would be persuaded to remain in Turkey and wait for resettlement rather than attempt a dangerous voyage to Europe.

Recommendation Two: Provide resources for education, employment, and security assistance for refugees in Lebanon and Jordan.

Weakened front line states could also threaten the EU-Turkey deal. Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan currently host over 1 million displaced Syrians. In Jordan, UNHCR calculates a funding gap of $448 million out of the $1.19 billion deemed necessary to support refugees in Jordan in the short-term. As of late 2015, 85% of Syrian families in Jordan are now food insecure or vulnerable to food insecurity, compared to 48% in 2014.[4] In Lebanon, the absence of camps has driven most refugees into makeshift conditions or abandoned buildings. 70% of Syrians in Lebanon now live below the Lebanese extreme poverty line.[5]

The EU-Turkey deal promises 6 billion Euros to Turkey, but does not provide similar funding for Lebanon and Jordan. Financial support matters immensely to the decisions of displaced Syrians and the fragile stability in front line states. In September 2015, the World Food Programme was forced to cut the value of the food vouchers distributed to those in need. An assessment of the effects of these cuts on vulnerable Syrians in Jordan has shown that 13% of families sent at least one family member to beg (up from 4% before the cuts), and 80% of families borrowed money to pay for basic food needs. Almost half of those interviewed said they would consider leaving Jordan – either for Europe (20%) or back to Syria (26%) – if they did not receive WFP food assistance in the future.[6] While increased donations have recently allowed the WFP to reinstate the full value of the food vouchers, these repercussions demonstrate the importance of ongoing financial support from the US and others. If conditions in the front line states worsen, many refugees would proceed towards Europe and the sudden pressure might fracture the fragile deal.

To prevent this, the US should assess financial shortfalls and where necessary increase its already substantial contributions. Financial support to Jordan and Lebanon should continue to be targeted at programs that aid integration, education, and labor market access. The US should also provide security assistance for border security and protection of vulnerable populations.

Jordan

The Government of Jordan, in partnership with the UN, donors, and NGOs, has recently produced a three-year refugee response plan (“Jordan Response Plan to the Syria Crisis 2016-2018”).[7] The JRP 2016-2018 lays out a comprehensive plan to move from a crisis response framework to a resilience-based approach. While the international community has supported this plan, total financial commitments to date total only a quarter of the $7.9 billion required to implement it.[8]

Future support for Jordan should take the form of:

- Increased financial and political support for the JRP in order to ensure the success of Jordan’s resilience-based approach. In particular, Jordan has indicated that they will be able to develop 200,000 job placements suited for Syrian refugees – but that this total could be increased if donor countries increase their financial support for five development zones Jordan plans to invest in across the country.

- Pressure to carry out the proposal to relax EU trade rules governing exports from Jordan to the EU, which would make it easier for Jordanian producers to qualify for free access to EU markets. The EU has promised to consider this approach, and David Cameron has further advocated for the change. The US already has a similar provision, allowing development of around $1 billion of Jordanian exports. This shift would increase Jordan’s competitiveness in trade and promote the type of economic development that will enable new job placements for both Jordanians and Syrians. Moreover, it will reinforce a mutual commitment of support between the EU and Jordan.

Lebanon

Lebanon hosts the highest number of Syrian refugees per capita. In contrast to Jordan, Lebanon’s political dysfunction and lack of institutional capacity make it ill-prepared to provide suitable support for refugees. Furthermore, public and political attitudes towards refugees make a focus on long-term planning and resilience challenging. Any long-term planning and development the government might do on behalf of refugee populations rather than needy Lebanese is seen as politically toxic. No amount of external pressure will change this political reality.

Lebanon’s policy of discouraging refugee documentation compromises aid and service delivery to these populations. In May 2015, at Lebanon’s request, UNHCR stopped registering new refugees. High fees (approximately €180 per adult) for the renewal of legal refugee residence status encourage refugees already in-country to become undocumented.[9] As a result, many refugees are undocumented and lack access to humanitarian support. In 2015, 89% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon reported lack of food, or money to buy it, in the previous 30 days.[10]

Successful support for Syrian refugees in Lebanon will by necessity need to work around, not through, government channels. This support can be implemented in two major ways:

- Direct grant-making to trusted local NGOs. Direct grant-making to legitimate NGOs on the ground avoids political complications and channels the money directly to organizations equipped to implement programming. While legitimate local NGOs are not plentiful, organizations like Zeitooneh are well-respected and have the capacity to implement increased refugee support programming.

- Partnerships with the private sector. The Middle East Investment Initiative, a non-profit organization focused on sustainable economic growth, has developed a Middle East Recovery Plan focused on partnerships and favorable loan structures with local private sector companies. This approach is promising in that it connects available funding directly to companies who can employ those in need. Donor companies could set up grant programs that specify a certain quota of refugee employees.

Lebanon’s political situation makes aid delivery and refugee support difficult, but not impossible. Donor countries should work with local NGOs and private companies to support high-need areas such as food and water, education, and employment opportunities.

Recommendation Three: Support Search and Rescue in the Mediterranean to prevent migrant drownings on the Africa-Italy Route

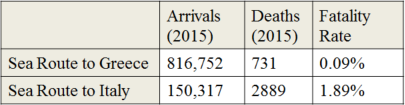

One of the unintended consequences of the EU-Turkey deal may be to increase the incentives for migrants to attempt the far more dangerous sea crossing from North Africa to Italy. This route was used by over 150,000 migrants in 2015, but the bulk of the flow switched to the Turkey-Greece route because it was much safer. 78% of migrant drownings in 2015 were from those trying to reach Italy, even though only 15% of migrants were using that route. The table below shows that the sea route to Italy is about 20 times as dangerous as the route to Greece.

All data from International Organization for Migration, 2015 [11]

If more migrants attempt the sea route to Italy, drownings in 2016 will dwarf the 3,692 reported in 2015 by the International Organization for Migration. There is some evidence that more people are already attempting the Italy sea route. In the week ending on April 14, 4,448 people arrived in Italy by sea, up from an average of about 2800 a week for the previous three weeks.[12]

Because daily weather patterns have significant effects on sea migration, it is too early to say if migrant flows on the sea route to Italy will significantly increase. Despite this, Italy and surrounding countries are already taking precautions. The Austrian defense minister, Hans Peter Doskozil, announced that his country would strengthen border controls at the Brenner Pass, including fences similar to what Austria has already built at the Slovenian border.[13] Besides the trade disruption, this could have the effect of bottling up migrants within Italy.

If this is the early stages of another refugee crisis this summer, it will be a different crisis. The issue of children will be more salient: nearly 2,700 of the 19,000 arrivals in Italy through the end of March were under 18 years old and travelling alone.[14] The ethnic and national make-up of these migrants is different, featuring more Africans and fewer Afghans, Syrians, and Iraqis. Finally, the issue of drowning will be more pressing because of the longer sea journey over stormier waters. The mid-April drowning of up to 500 migrants in a single incident off Libya’s coast illustrates the deadly risks of this route.

The United States cannot solve the root problems in Africa that are driving these refugees, but it can take action to reduce human suffering. The US should support the NATO mission in the Aegean and Mediterranean to interdict seaborne refugees heading to Greece and Italy. There is a small NATO force in the Mediterranean with vessels from Germany, Canada, Greece, Turkey, and the UK. Their mission is to interdict human smugglers and rescue refugee boats that are sinking. The US should support this effort in two ways:

- The US should use its aerial reconnaissance capabilities in the Mediterranean to provide early warning to NATO vessels of refugee movement. The US has a squadron of P-3 Orion aircraft in Sicily that could be tasked to watch out for vessels in distress or human smuggling operations. This would increase the efficiency of the NATO force without requiring more vessels.

- The US should use its ability under Title 10, Section 1033 of the US Code to distribute non-lethal aid to the Italian government to support its interdiction efforts. The specific aid package should reflect the Italian government’s needs but might include patrol boats, navigation equipment, communications, and search and rescue equipment.

The EU has been rightfully criticized for its slow response to the refugee crisis. The developing situation in Italy is a second chance to be proactive in addressing migrants before it becomes a humanitarian disaster. If the EU is willing to do this, they should find a willing partner in the United States to provide logistical and financial support.

Conclusion

In 1947, America came to the aid of a devastated Europe with the Marshall Plan. The current refugee flow threatens the unity of Europe with the same urgency. As walls go up on European borders, the Schengen agreement seems more tenuous every week. The EU-Turkey deal is the last, best effort to manage migrant flows in a humane yet sustainable way. The criticisms by humanitarian organizations of the deal as it is currently being implemented are valid, but US involvement can mitigate their concerns. American leadership can support the EU-Turkey deal and make it more humane and efficient. American involvement in this crisis will strengthen the Atlantic alliance, offer crucial political support to leaders, such as Angela Merkel, seeking to sustain domestic political support for refugee resettlement, and send a powerful message to those European leaders seeking to shut the doors on the desperate and destitute.

The US will also have a stronger geostrategic position if it supports the EU-Turkey deal. A strong and unified Europe is the principal check against an aggressive and expansionary Russia. The Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered justified concern in Eastern Europe that Putin might target them next. When the US supports its allies in Europe, the result strengthens both as they face the rising power of Russia.

This refugee crisis is not just a European problem, any more than it is simply a humanitarian challenge. For the United States, it presents a challenge and a strategic opportunity for leadership. The time to act is now. As the weather improves and migrant flows begin to surge again, the pressure on Europe is bound to increase. If America and Europe can act together in this crisis, they will provide hope for desperate people and demonstrate to a doubtful world that free nations can actually solve their most pressing problems.

About the Authors

Michael Ignatieff is Edward R. Murrow Professor of Practice at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. He is a Canadian writer, teacher and former politician.

Juliette Keeley is a Masters in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School. Before Harvard, she was a Peace Corps volunteer in Guinea and worked on education policy with the NYC Department of Education.

Betsy Ribble is a Masters in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School. Before Harvard, she worked in communications and policy at Change.org, the world’s largest petition platform.

Keith McCammon is a fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and a Masters in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is a former U.S. Army infantry officer and military analyst.

Endnotes

[1] Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. “UNHCR Expresses Concern over EU-Turkey Plan.” UNHCR. Accessed April 28, 2016. http://www.unhcr.org/56dee1546.html

[2] “Safe Third Countries”, Presidential Decree number 113, Part A, Chapter C, Article 20. http://www.refworld.org/docid/525e84ae4.html

[3] Kingsley, Patrick. “Greece May Have Deported Asylum Seekers by Mistake, Says UN.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 05 Apr. 2016. Web. 29 Apr. 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/05/greece-deport-migrants-turkey-united-nations-european-union

[4] World Food Programme. “Syria Crisis Response: Jordan Fact Sheet.” March 2016.

http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp264172.pdf

[5] United Nations News Service. “Conditions of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon Worsen Considerably, UN Reports.” UN News Service Section, December 23, 2015. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=52893#.VtXP8BgRdAb

[6] World Food Programme. “Syria Crisis Response: Jordan Fact Sheet.” March 2016.

http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp264172.pdf

[7] “Jordan Response Plan for the Syria Crisis: 2016-2018.” http://www.jrpsc.org/

[8] “Jordan Secures $1.7b Grants, Grant Equivalents at London Conference.” Jordan Times, February 4, 2016. http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-secures-17b-grants-grant-equivalents-london-conference

[9] European Commission. “Lebanon: Syria Crisis Echo Factsheet.” February 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/lebanon_syrian_crisis_en.pdf

[10] Joint report from the WFP, UNHCR, and UNICEF. “Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: 2015 Report.” http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=10006

[11] Migration Flows – Europe. Rep. International Organization for Migration, 14 Apr. 2016. Web. 29 Apr. 2016. http://migration.iom.int/europe/

[12] “Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean.”Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean. United Nations High Commisioner for Refugees, 20 Apr. 2016. Web. 29 Apr. 2016. http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

[13] Yardley, Jim. “After Europe and Turkey Strike a Deal, Fears Grow That Migrants Will Turn to Italy.” The New York Times, 14 Apr. 2016. Web. 29 Apr. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/15/world/europe/after-europe-and-turkey-strike-a-deal-fears-grow-that-migrants-will-turn-to-italy.html

[14] Ibid.