Videos

Digging into crime data to inform news coverage across beats

Reports & Papers

A new report from Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy analyzes news coverage of the 2016 presidential primary races and how it affected the candidates’ chances of winning the nomination, concluding that coverage of the primaries focused on the horse race over the issues – to the detriment of candidates and voters alike.

The report picks up where the Center’s previous report concluded, analyzing coverage of Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich, Hillary Clinton, and Bernie Sanders from January through June 2016.

Some of the questions Patterson investigates include:

The Shorenstein Center study is based on an analysis of news statements by CBS, Fox, the Los Angeles Times, NBC, The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. The study’s data were provided by Media Tenor, a firm that specializes in the content analysis of news coverage.

Read the other reports in this series:

News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions: Negative News, Lacking Context.

New: News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters.

Presidential primaries are unique in their form. Rather than allowing voters to directly choose a nominee, as is the case with House and Senate primaries, they are indirect—the voters choose delegates who in turn select the nominees. The serial nature of presidential primaries is also distinctive. Whereas House and Senate primaries are conclusive, a presidential primary is not. Nominations are decided by the results of fifty separate state contests spread out over several months. Finally, presidential primaries employ proportional representation—an electoral method rarely used in U.S. elections. A state’s “losers” get a proportional share of its delegates.

The complex nature of the presidential primary system does not sit easily with news values.

The complex nature of the presidential primary system does not sit easily with news values. The news, as Walter Lippmann noted nearly a century ago, is a story of obtruding events and not the social base from which they stem.[1] The news is also a hurried story. As New York Times columnist James Reston noted, journalism is “the exhilarating search after the Now.”[2] The result is that the press’s version of a presidential campaign is a refracted one, shaped as much by news values as by political factors. It’s a version that can help, or hurt, a presidential hopeful’s chances of winning the party’s nomination.

Few nominating campaigns illustrate that point more clearly than the 1976 race for the Democratic nomination. A poll before the first primary found that any of the four liberal Democrats in a one-on-one matchup would easily defeat the one centrist, Jimmy Carter.[3] But there was one of him, and four of them—plus one in the wings in the form of the undeclared Hubert Humphrey. In the Iowa caucuses, Carter got 26 percent of the vote, while 37 percent of the votes were cast for “undecided,” which voters were told was the way to cast a vote for Humphrey.

The press ignored the undecided ballots and declared Carter the victor. “He was the clear winner in this psychologically crucial test,” declared CBS News.[4] Buoyed with the media bonanza from his Iowa showing, Carter then narrowly won the New Hampshire primary, edging Morris Udall, who was competing with Birch Bayh, Fred Harris, and Sargent Shriver for the liberal vote. Although Carter won New Hampshire by fewer than five thousand votes and had received barely more than a fourth of the total vote, Newsweek declared Carter to be “the unqualified winner.”[5] In the period between New Hampshire and the ninth primary in Pennsylvania, Carter received as much news coverage as all of his Democratic rivals combined,[6] who at that point threw in the towel. Later, Jerry Brown and Frank Church entered the race as liberal alternatives to Carter. They faced off with him in eight states, winning all but two contests, usually by wide margins. By then, however, Carter had accumulated enough delegates to secure his nomination.

Although the 1976 Democratic race is a clear-cut case, the press has played a key role in every contested presidential nominating race since 1972—the first election in which states were required to choose their convention delegates through a caucus or primary election. Before the change, the political parties acted as the principal intermediary between aspiring candidates and voters. After the change, the media assumed that role. Voters’ response to the media’s portrayal of the candidates would, of course, be filtered through their political biases. But that filtering would take place in response to an earlier filter—that of journalistic bias.

How did the news media cover the 2016 presidential primaries and how did it affect the candidates’ chances? These questions will be examined through a look at the election reporting between January 1 and June 7 (the date of the final state contests) in eight major news outlets—CBS, Fox, the Los Angeles Times, NBC, The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post.

This study is the second in our series of reports on media coverage of the 2016 presidential election. The first examined news coverage during 2015—the so-called “invisible primary” stage of the campaign. The data for our studies are provided by Media Tenor, a firm that specializes in collecting and coding news content. Media Tenor’s coding of print and television news stories is conducted by trained full-time staff members who visually evaluate the content. Coding of individual actors (e.g., presidential candidates) is done on a comprehensive basis, capturing all statements of more than five lines (print) or five seconds (TV) of coverage for a given actor. Coders identify relevant themes (topics) for all actors in a given report and evaluate tone (positive or negative) on a six-point scale. These tonality ratings are then combined to classify each report for each actor as being negative, positive, or having no clear tone.

The presidential nominating process unfolds in stages, beginning with the four single-state contests in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina. Each stage has its own media dynamic, as this paper will show. Before discussing the separate stages, it’s useful here to briefly describe a few of the major tendencies in campaign coverage over the full course of the primaries and caucuses.

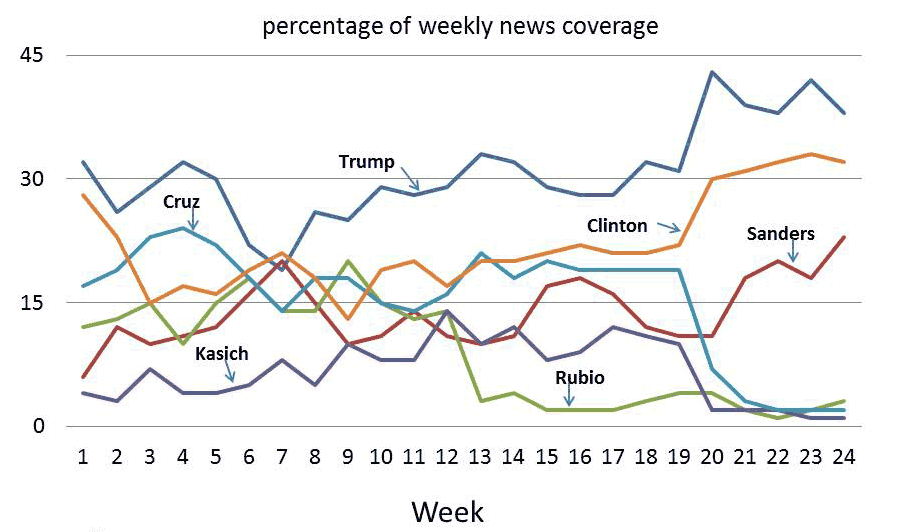

Coverage Levels. The news media’s fascination with Donald Trump’s candidacy, which began in 2015, carried into the primary election phase. Week after week, Trump got the most press attention (see Figure 1). There was not a single week when Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, or John Kasich topped Trump’s level of coverage. During the time that Rubio was an active candidate for the Republican nomination, he got only half as much press attention as Trump. During the time they were still in the race, Cruz received roughly two-thirds the coverage afforded Trump while Kasich got only a fourth.

Figure 1: Candidate’s News Coverage, Week by Week

After Cruz and Kasich quit the race in early May, clearing the way for Trump’s nomination, it might be thought that the press would shift its attention to the on-going Democratic race. Even then, however, Trump was the headliner, receiving more coverage than either Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders in each of the last five weeks of the primary campaign.

The media’s obsession with Trump during the primaries meant that the Republican race was afforded far more coverage than the Democratic race, even though it lasted five weeks longer. The Republican contest got 63 percent of the total coverage between January 1 and June 7, compared with the Democrats’ 37 percent—a margin of more than three to two.

Sanders in particular struggled to get the media’s attention. Over the course of the primary season, Sanders received only two-thirds of the coverage afforded Clinton. Sanders’ coverage trailed Clinton’s in every week of the primary season. Relative to Trump, Sanders was truly a poor cousin. He received less than half of the coverage afforded Trump. Sanders received even slightly less coverage than Cruz, despite the fact that Cruz quit the race and dropped off the media’s radar screen five weeks before the final contests. For her part, Clinton got slightly less than three-fourths of the press attention given to Trump. Nevertheless, she was, except for Trump, the most heavily covered candidate during the primary period.

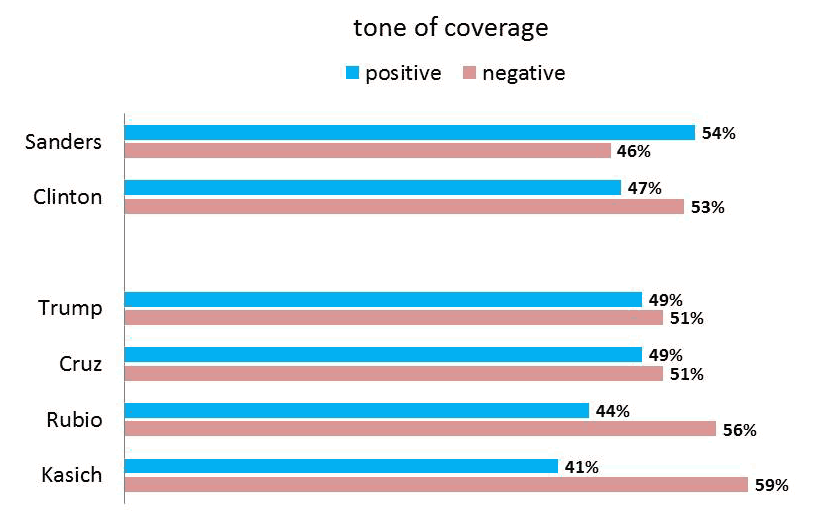

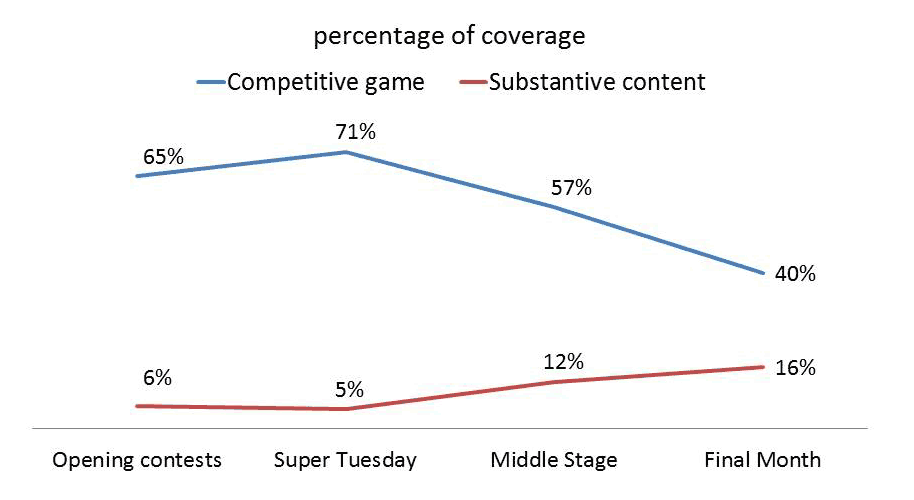

Coverage Tone. Our earlier study found that, in 2015, Sanders received the most positive coverage of any of the presidential contenders. That pattern carried into the primaries. During the period from January 1 to June 7, positive news statements about Sanders outpaced negative ones by 54 percent to 46 percent (see Figure 2). In fact, Sanders was the only candidate during the primary period to receive a positive balance of coverage. The other candidates’ coverage tilted negative, though in varying degrees. Clinton’s coverage was 53 percent negative to 47 percent positive, which, though unfavorable on balance, was markedly better than her 2015 coverage when she received by far the most negative coverage of any candidate. During that year-long period, two-thirds (69 percent to 31 percent) of what was reported about Clinton was negative in tone.

Figure 2: Tone of Candidates’ News Coverage

Trump’s coverage during the primary period was almost evenly balanced, with positive statements about his candidacy (49 percent) nearly equal to negative ones (51 percent). However, the tone of his coverage varied markedly over the course of the primary season. During the period when the Republican nomination was still being contested, Trump’s coverage was positive on balance. News statements about Trump during this period were 53 percent positive to 47 percent negative—nearly as positive as Sanders’. But after Cruz and Kasich dropped from the race in early May, Trump’s coverage nosedived. Over the final five weeks of the primary season, 61 percent of news statements about Trump were negative and only 39 percent were positive—a level of negativity exceeded only by Clinton’s coverage during 2015.

The press did not heavily cover the candidates’ policy positions, their personal and leadership characteristics, their private and public histories…Such topics accounted for roughly a tenth of the primary coverage.

During the period that Cruz was still an active candidate, his coverage was almost evenly balanced in tone—49 percent positive to 51 percent negative. He fared much better than either Rubio or Kasich, who had the least favorable coverage of any top contender. While Rubio was an active candidate, his coverage was 56 percent negative to 44 percent positive. During his active candidacy, Kasich’s coverage was 59 percent negative to 41 percent positive.

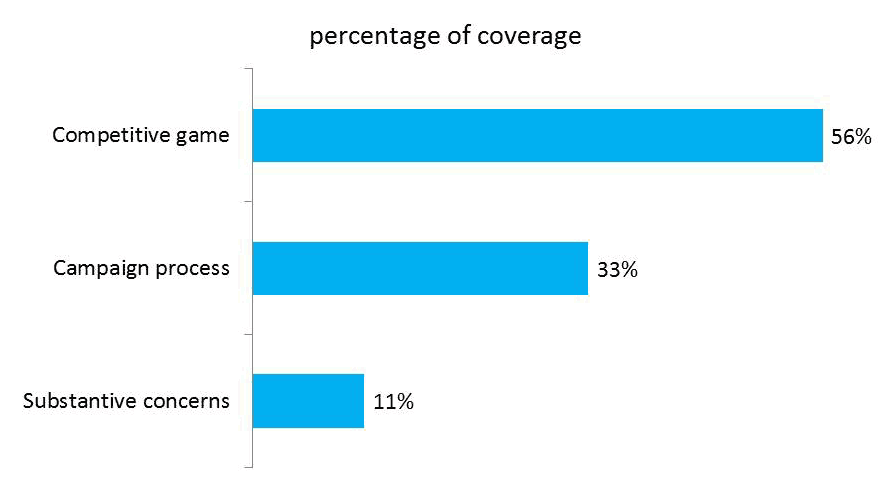

Coverage Topics. Election news during the primary period was dominated by the competitive game—the struggle of the candidates to come out on top. Overwhelmingly, election coverage was devoted to the question of winning and losing. Poll results, election returns, delegate counts, electoral projections, fundraising success, and the like, along with the candidates’ tactical and strategic maneuvering, accounted for more than half of the reporting (see Figure 3).[7]

Figure 3: Coverage Topics

Second in terms of amount of coverage was the election process itself. Much of the reporting focused on topics such as the election timetable, upcoming debates, the candidates’ appearance schedules, and the rules of the nominating process. Such topics accounted for roughly a third of the campaign coverage during the primary period.

Substantive concerns were last in terms of the coverage allocation. The press did not heavily cover the candidates’ policy positions, their personal and leadership characteristics, their private and public histories, background information on election issues, or group commitments for and by the candidates. Such topics accounted for roughly a tenth of the primary coverage.

There was no appreciable variation between the Republican and Democratic coverage. In each case, the competitive game was the primary focus and in nearly equal amounts, while substantive concerns got the least amount of attention, again in nearly equal amounts.

Questions. These coverage patterns are the basis for the questions that will be addressed in the sections that follow, namely:

Following a schedule adopted in 2008, the presidential nominating process starts with stand-alone contests in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina. Other states are prohibited by party rules from staging their primary or caucus until the last of these contests is held.

Four candidates—Trump, Cruz, Rubio, and Kasich—were thought to have a realistic chance of winning the Republican nomination as the Iowa caucuses approached. Cruz finished first in Iowa, garnering 28 percent of the caucus vote, compared with 24 percent for Trump, 23 percent for Rubio, and a mere 2 percent for Kasich. Trump then placed first in New Hampshire’s primary, with 35 percent of the vote to Kasich’s 16 percent, Cruz’s 12 percent, and Rubio’s 11 percent. Trump prevailed again in South Carolina’s primary, finishing first with 33 percent of the vote, while Rubio was second with 23 percent, Cruz with 22 percent, and Kasich with 8 percent. Trump’s largest victory margin came in the Nevada primary, where he received 46 percent of the vote, trailed by Rubio (24 percent), Cruz (21 percent), and, at a distant fourth, Kasich (4 percent). In terms of projected delegates, Trump emerged from the early contests with a wide lead. He accumulated 82 delegates, 50 of which came from his victory in South Carolina’s winner-take-all primary. Cruz garnered 17 delegates, while Rubio picked up 15, and Kasich obtained 6.

During the period spanned by the first four contests, Trump dominated the news coverage (see Figure 4). He garnered 37 percent of the Republican coverage, compared with Cruz’s 28 percent, Rubio’s 25 percent, and Kasich’s 10 percent. Trump’s coverage was also highly favorable. Positive news statements about his candidacy outnumbered negative ones by 57 percent to 43 percent. Cruz also had a positive balance, though by a smaller margin—55 percent positive to 45 percent negative. Rubio’s coverage tilted sharply toward the negative side. His negative press far outpaced his positive press—61 percent to 39 percent. Kasich’s figures were nearly as negative as Rubio’s.

Figure 4: Republican Candidate Coverage — Initial Contests

These figures reflect the news media’s tendency to treat early primaries and caucuses as decisive events, with clear winners and losers. With his three victories, Trump got most of the headlines, and the bulk of the coverage. Victory for Trump was also his path to positive coverage. During the primaries, journalists tend to build their narratives around the candidates’ positions in the race. This focus leads them into four storylines: a candidate is “leading,” “losing,” “gaining ground,” or “losing ground.” Of the four storylines, the most predictably positive one is that of the “gaining ground” candidate. It’s a story of growing momentum, rising poll numbers, ever larger crowds, and electoral success. The storyline invariably includes negative elements, typically around the tactics that the candidate is employing in the surge to the top. But the overall media portrayal of a “gaining ground” candidate is a positive one. That was the thrust of Trump’s coverage in the opening contests of the 2016 campaign. The first line in The Washington Post’s story out of South Carolina exclaimed, “Donald Trump commandingly won the South Carolina primary on Saturday night, solidifying his position as the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination. . . .”[8]

The extent to which the election game was driving the coverage is evident in the difference between Rubio’s coverage and Cruz’s….Unlike Cruz, Rubio failed to win an opening contest.

The extent to which the election game was driving the coverage is evident in the difference between Rubio’s coverage and Cruz’s. In the context of the nominating process as a whole, Rubio’s performance closely matched that of Cruz. The two candidates had acquired nearly the same number of delegates and the difference in their vote totals in each of the first four contests was 5 percentage points or less. Rubio had finished ahead of Cruz in two states, while Cruz had come out ahead in the other two. But their performances differed in one key respect, and it spelled the difference between good press and bad press. Unlike Cruz, Rubio failed to win an opening contest. Cruz’s victory in Iowa was the largest source of his positive press coverage during this stage of the campaign. He was in the headlines for much of the ensuing week, touted as conservative Republicans’ best hope. For his part, Rubio never had a single week where his positive press outpaced his negative press. He had been pegged as “the Republican establishment’s best chance” on the eve of the Iowa caucuses, but failed to come out on top there, or in any of the three states that followed. Rubio was a “losing ground” candidate, and there’s very little that’s positive in that narrative. The reason for the decline in the candidate’s fortune is the main ingredient of the “losing ground” story. In Rubio’s case, the press highlighted his stumbling performance in the New Hampshire primary debate as the cause. “In the wake of the debate debacle,” The New York Times reported, Rubio’s advisors “are now grappling with the weaknesses of a strategy constructed almost entirely around the political talents of its candidate. Even his longtime admirers seemed unnerved, and their faith in him shaken.”[9]

The media’s focus on the election game was so heavy in this period that the candidates’ character and policies were almost lost, ranging from a low of 4 percent of Rubio’s coverage to a high of 8 percent for Trump’s. The tone of this coverage was negative for all the Republican contenders, running from 4-to-1 negative for Trump to 3-to-2 negative for Rubio.

On the Democratic side, Clinton finished first in Iowa, though by a razor-thin margin. Eight days later, in New Hampshire’s primary, Sanders easily topped Clinton, 60 percent to 38 percent. Then, in the Nevada caucuses, Clinton narrowly prevailed, 53 percent to 47 percent, followed by a lopsided 76-24 percent victory in the South Carolina primary. The projected delegate counts from the four states divided 91 delegates for Clinton and 65 for Sanders.

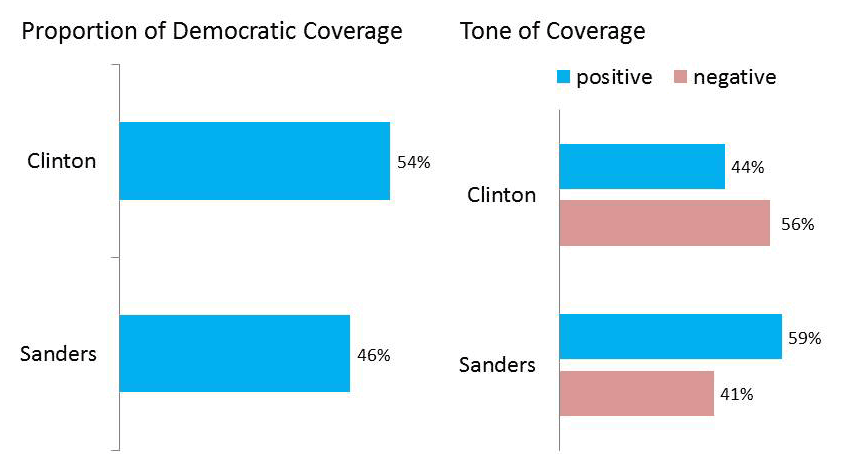

The media coverage in one respect mirrored the split decision. Press attention divided narrowly in Clinton’s favor. She got 54 percent of the Democratic coverage to Sanders’ 46 percent (see Figure 5). It was the first time in the campaign that Sanders received nearly as much press attention as Clinton. Nevertheless, the advantage he might have received from the heightened attention was diminished by the fact that the Democratic race was the undercard. During the four opening contests, the Republican race received 58 percent of the coverage while the Democratic contest got only 42 percent.

Figure 5: Democratic Candidate Coverage — Initial Contests

Nevertheless, Sanders’ coverage during the opening stage of the primaries was the most positive of any candidate. His good press outweighed his bad press by 59 percent to 41 percent—the largest favorable margin of any of the contenders at any point in the primary season. In contrast, Clinton’s coverage tilted negative. Negative statements about her candidacy outnumbered positive ones by a margin of 56 percent to 44 percent.

Why, despite prevailing in three of the four contests, was Clinton portrayed negatively? Why was she not afforded the positive coverage typically granted to a first-place finisher? The answer lies in an observation made by journalist Jules Witcover shortly after the nominating process was changed to a system of primaries and caucuses in the early 1970s. “The fact is,” he wrote, “that the reality of the early going of a presidential campaign is . . . the psychological impact of the results—the perception by press, public, and contending politicians of what has happened.”[10]

The perception that Clinton had a lock on the Democratic nomination diminished journalists’ interest in the Democratic race generally and in Sanders’ candidacy particularly.

The “psychological impact” in Trump’s case was that he was doing “better than expected,” which is a positive narrative. In Clinton’s case, the “psychological impact” was a belief that she was doing “worse than expected,” which is a negative story. Although her three victories brought her positive press on balance, it came at a discount. Her victory in Iowa was portrayed as underwhelming and her win in Nevada was degraded as “narrow”—it was a state she was “once expected to win by double digits.”[11] A persistent theme of Clinton’s coverage was that voters couldn’t relate to her—she was pictured as too remote to reach them emotionally. “Her inevitability,” said one news report, “has dissolved because of her campaign’s inability to connect with voters.”[12] References to Clinton’s issues and character, though only a small part of her coverage during this stage of the campaign, also contributed to her negative coverage. Such references were 8 to 1 negative to positive, by far the most negative of any candidate during this period.

“Psychological impact” also played into Sanders’ press coverage. Sanders was said to be doing “surprisingly well,” a positive narrative. Sanders’ character and policies were also sources of good press—in fact, he was the only candidate portrayed positively by the media on these dimensions. On the other hand, at this stage in the campaign, Sanders—unlike Clinton, Trump, Cruz, or Rubio—was not perceived as a candidate who could actually win the party’s nomination. Although his resounding New Hampshire victory dampened the claim, it returned in force after his losses in Nevada and South Carolina. In reporting his South Carolina defeat, for example, The Washington Post noted that “Sanders has already accomplished a huge amount in this race—including dragging Clinton to the ideological left . . . . But, exerting influence—even considerable influence—over the nominee’s priorities is not the same thing as having a real chance to be the nominee in your own right.”[13] The perception that Clinton had a lock on the Democratic nomination diminished journalists’ interest in the Democratic race generally and in Sanders’ candidacy particularly. Sanders’ press attention in the early going trailed not only that of Clinton and Trump but also that of Cruz and Rubio.

On the first Tuesday following the last of the four opening contests, in what was called Super Tuesday, twelve states held a primary or caucus. On the ensuing weekend, an additional five states held contests. The next Tuesday, in what was labeled “Mini Tuesday,” four more states held elections. Some states held a contest in only one party—eighteen Republican elections and sixteen Democratic elections were held. No other period of the campaign had a comparable number of contests in such a short span of time.

The eighteen states holding Republican contests on or near Super Tuesday split in Trump’s favor. He finished first in eleven of them, with Cruz prevailing in six states and Rubio in one. The delegate distribution was closer, with Trump picking up 367 delegates to Cruz’s 326. Rubio got 109 and Kasich acquired 49. Soon thereafter, Rubio dropped from the race.

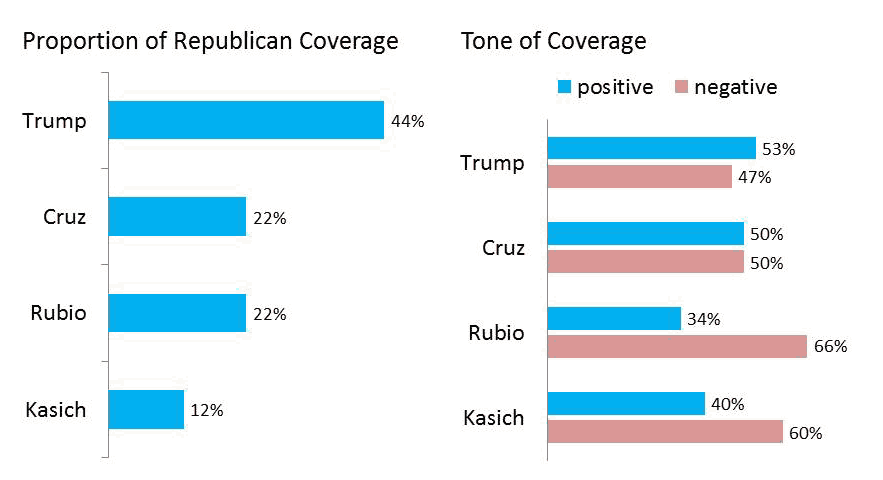

During the two weeks of the Super Tuesday stage, Trump had the limelight. He got 44 percent of the coverage afforded the top four Republican candidates, which was twice that of Cruz or Rubio and nearly four times that of Kasich (see Figure 6). Trump was also the only Republican contender to have a favorable balance of coverage during this period, with positive statements outpacing negative ones by 53 percent to 47 percent. In contrast, Rubio was mired in bad press. Negative statements about his candidacy outnumbered positive ones by two to one.

Figure 6: Republican Candidate Coverage—Super Tuesday Period

At no point in the campaign did vote projections, tabulations, and assessments so thoroughly dominate coverage as during the Super Tuesday period. Coverage of the candidates’ character and policies averaged but 5 percent of the total, ranging from a high of 9 percent in Clinton’s case to a low of 2 percent in Rubio’s.

Although the Iowa and New Hampshire contests were more eagerly awaited by the press, Super Tuesday had the greatest concentration of contests, giving journalists a range of choices. State-by-state vote results rather than the delegate counts drove the media’s narrative. As the candidate with the most wins, Trump got by far the most coverage. His coverage was also favorable on balance, although less so than during the opening contests. Trump had transitioned from a “gaining ground” candidate to a “leading” candidate, which is a less certain source of good news. Any sign of weakness—which in Trump’s case was supplied with Cruz’s victories—is a source of “bad news.” Under the headline “Cruz Crushes Trump in Kansas,” one news story said that “Texas Sen. Ted Cruz won the Kansas Republican caucuses by an overwhelming margin on Saturday, more than doubling Donald Trump’s share of the vote. Kansas represents an upset victory for Cruz, as polls showed him trailing Trump heading into Saturday’s vote.”[14] Trump’s character and policies were also a source of negative coverage. Although they received only a small amount of press attention, the references divided more than 10-to-1 negative over positive.

Cruz finished first in six states during the Super Tuesday period but was eclipsed by the media shadow cast by Trump, getting only half as much press attention. Cruz’s victories were a source of positive press, which was offset by the bad press accompanying his nine losses to Trump. He was doing well but not well enough, which thrust him in the role of a “losing ground” candidate. In a Super Tuesday report, the Los Angeles Times nearly dismissed Cruz’s wins in Oklahoma and Texas, saying, “But even as Cruz called for others to quit the race, he faces a steep road ahead as the contest shifts away from the South and Cruz’s advantage among its religiously oriented, deeply conservative voters.”[15]

As for Rubio, he was in the unenviable position of a “loser,” a predictable source of bad press. Rubio’s lone bright spot was a first-place finish in the Minnesota caucuses. Otherwise, he had a lousy news image. “Rubio’s fortunes are in free fall,” intoned one reporter. [16]

Clinton and Sanders split almost evenly the sixteen state Democratic contests on or near Super Tuesday. She prevailed in nine states, all of which held primaries. He finished first in seven states, four of which held caucuses. The delegate count wasn’t nearly as close, as Clinton prevailed in the highly populated states. She acquired 670 delegates in this period to Sanders’ 469.

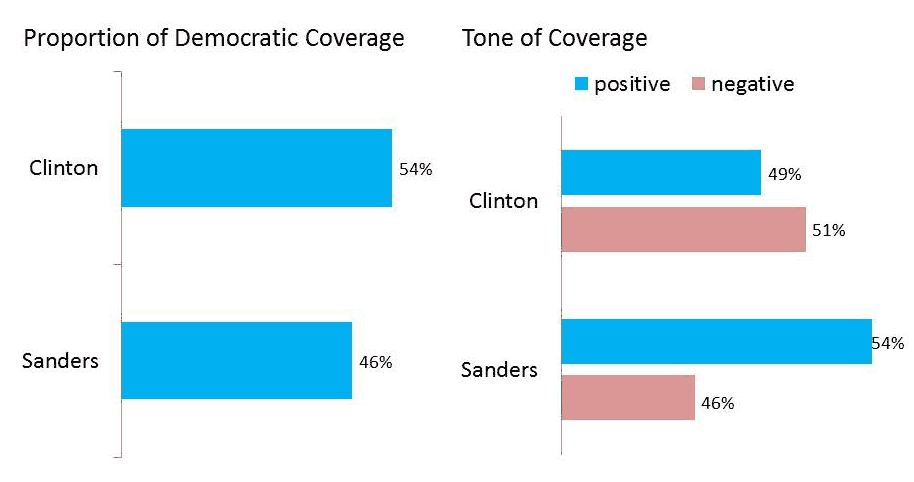

The media coverage on one level mirrored the ratio of wins and losses rather than the ratio of delegates. Sanders received nearly as much press attention as did Clinton, getting 46 percent of the Democratic coverage to her 54 percent (see Figure 7). However, as was true of earlier stages of the campaign, the Democratic race took a back seat to the Republican race. Two-thirds of the election coverage went to the Republican race. Sanders was not a forgotten man, but his coverage trailed even that of Rubio, who was pulled toward center stage by Trump. Whatever else Rubio derived from “little Marco,” it thrust him into the headlines.

Figure 7: Democratic Candidate Coverage—Super Tuesday Period

Sanders’ coverage during the Super Tuesday period, as was true of earlier stages, was the most favorable of any candidate. Positive statements about Sanders outpaced negative ones by 54 percent to 46 percent. His electoral successes were a source of good news, as were his character and policy positions.

For her part, Clinton received marginally more negative press than positive press, continuing a string of fourteen straight months in which her press coverage was unfavorable in tone. As in previous stages of the campaign, her character and policies were a source of bad press. Nevertheless, the large number and close proximity of contests in the Super Tuesday period provided Clinton with her most favorable coverage to this point in the campaign. With vote projections, outcomes, and assessments nearly the whole story during these two weeks, Clinton’s victories provided enough good news to nearly tip the balance of her coverage into positive territory. Nevertheless, as in the opening stage, her victories came with a discount, as they continued to be judged in the context of her “expected” performance—the support she would have had if she was running a better campaign. “Some Clinton voters approached the polls with resignation, viewing the former secretary of state and first lady as merely the best of bad options,” said The Washington Post in reporting on her victory in Virginia’s primary.[17]

From the Super Tuesday period, after which Rubio soon dropped from the race, through Indiana’s primary on May 3, when Cruz and Kasich withdrew, twenty-one states held elections, which included twenty contests on the Democratic side and fourteen on the Republican side.

Trump placed first in eleven of the fourteen Republican contests, with Cruz winning two and Kasich winning his first and only contest—his home-state primary in Ohio. Trump easily won the delegate race during this period, accumulating 540 delegates to Cruz’s 159 and Kasich’s 95.

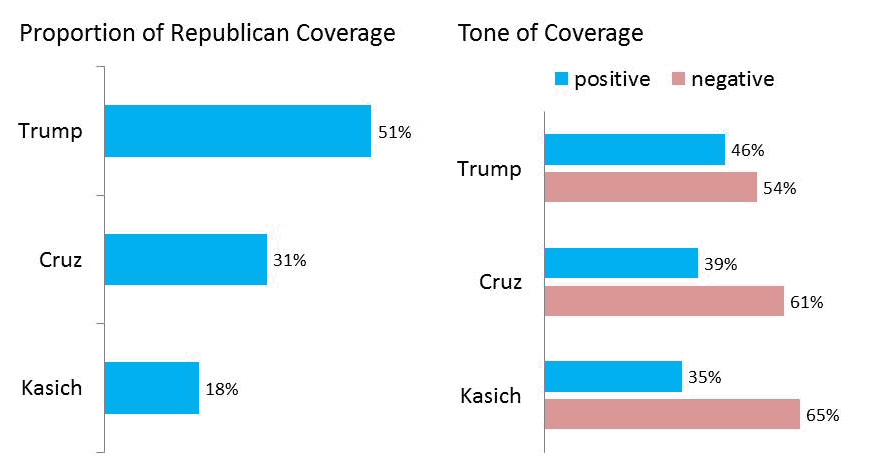

Trump thoroughly dominated press attention during the period, getting half the coverage afforded the Republican race, with Cruz getting a third and Kasich a sixth (see Figure 8). However, for the first time in the campaign, Trump’s coverage was unfavorable on balance—negative statements about him in the news outnumbered positive ones by 54 percent to 46 percent. Nevertheless, Trump’s press coverage was far more favorable than that of either Cruz or Kasich. They got hammered. Cruz’s coverage was 61 percent negative to 39 percent positive, while Kasich’s coverage split 65 percent negative to 35 percent positive.

Figure 8: Republican Candidate Coverage—Middle Stage

The degree to which the horse race drives the tone of candidate coverage is exemplified by Kasich’s and Cruz’s coverage during this period. The only week where the tone of Kasich’s coverage trended upward was the week of his only victory, the Ohio primary. In every other week, his coverage trended downward. Similarly, Cruz got a positive news bounce out of his victories in Utah and Wisconsin, but trended downward in other weeks.

Trump got positive press out of his electoral success. On the other hand, his issue stands and character were sources of negative press. By this point in the campaign, reporters had settled on their meta-narratives—the characterizations they were using in reporting on each of the candidates. In Trump’s case, that narrative included the claim that he was strong and decisive. Those positive elements rested alongside more negative ones—that he was bigoted, insulting, unprepared, and narcissistic. As his victories piled up and it was clear that Trump had his opponents on the run, the horse race got less press attention, reducing the positive press stemming from his electoral success. News references to his policies and character, though still the smaller share of his coverage, were increasing in number and were largely negative in tone. Such claims were typically expressed, not by journalists directly, but through the words of political opponents and voters. Said a Wall Street Journal article: “Mr. Trump’s cocky style has turned off some supporters, including Ralph Rife, a disabled coal miner in Slate Creek who voted for him but now says he can’t stomach him. ‘He’s like a loose cannon,’ Mr. Rife says.”[18]

Clinton finished ahead of Sanders in eleven of the twenty Democratic contests, all of which came in primary states. Sanders finished first in three primaries and in all six caucus states. The delegate count was close. Of the roughly 1,600 delegates at stake in these contests, Clinton had about a 50-delegate edge.

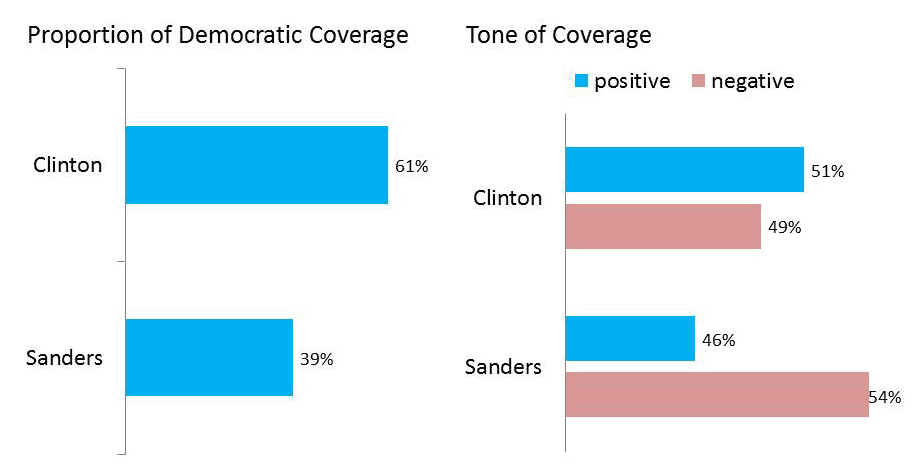

In terms of the volume of media coverage, the Democratic race was one sided, with Clinton getting 61 percent of the coverage to Sanders’ 39 percent (see Figure 9). And for the first time at any stage of the campaign, Clinton’s press was favorable on balance, though narrowly. Of the news statements with a clear tone, 51 percent were positive and 49 percent were negative. It was also the first time in the campaign that Sanders’ press tilted toward the negative. Positive statements about his candidacy were outweighed by the negative ones—46 percent to 54 percent.

Figure 9: Democratic Candidate Coverage—Middle Stage

The Democratic race continued to get second billing. During the middle stage, the Republican contest got 64 percent of the election coverage, compared with 36 percent for the Democratic race. The tilt was such that Clinton got barely more coverage than Cruz.

Sanders’ coverage was particularly sparse. He received only two-thirds as much coverage as Clinton, a reflection of the influence of “electability” on reporting. Sanders was unable during the primary season to convince journalists of his electability, which undercut his coverage. Cruz and Rubio, who were seen as viable contenders at one point or another of the primaries, got more press attention during their active candidacies than Sanders did, even though he placed higher in a much larger number of states than either of them. “Electability” also affected the tone of Sanders’ coverage, which tilted negative during this stage of the campaign. Near the top of its story of Sanders’ victory in the Indiana primary, for example, the Los Angeles Times said: “[B]ecause the Democrats distribute delegates proportionately according to each candidate’s vote totals, the primary results will have little impact on the actual race. The two candidates will split Indiana’s 83 pledged delegates roughly in half. That result benefits Clinton, who is closing in on a delegate majority.”[19]

The middle stage of the primaries was the first time in the campaign where a candidate other than Sanders got the most favorable coverage. That candidate was Clinton, who broke her months-long string of negative press, though by the narrowest of margins. Coverage of her character and issue positions remained deep in negative territory. On the other hand, her delegate count was increasingly a source of good press. “Bernie Sanders picked up a win Tuesday in Wisconsin’s primary,” NBC News reported, “while doing little to slow [Clinton’s] path to the eventual nomination. . . . Sanders had won 46 delegates to Clinton’s 36 in Wisconsin on Tuesday. In addition, Clinton had already secured seven super-delegates there — making the state’s overall count much closer.”[20]

During the campaign’s final month, eleven states held contests, though some of them took place in one party only. Contests in Nebraska and Washington were held only on the Republican side, while those in Kentucky and North Dakota took place only on the Democratic side.

Without active opposition, Trump swept the last nine Republican contests, picking up 427 delegates, enough to assure his nomination. His worst showing was a 61 percent victory in Nebraska’s primary, which was the first contest after Cruz and Kasich dropped from the race.

Although Trump no longer had active opposition, he received more news coverage in the last month than did either Clinton or Sanders, a development that has no possible explanation other than journalistic bias.

Although Trump no longer had active opposition, he received more news coverage in the last month than did either Clinton or Sanders, a development that has no possible explanation other than journalistic bias. Reporters are attracted to the new, the unusual, the sensational, the outrageous—the type of story material that can catch and hold an audience’s attention. Trump fit that interest as has no other candidate in recent memory. Even as his Republican rivals quit the race, journalists were unable to forego the story possibilities presented by Trump’s candidacy.

On the other hand, the tone of Trump’s press coverage during the last month of the primaries was negative. The mostly favorable coverage he had received earlier in the primary season had turned sharply downward (see Figure 10). Negative statements about his candidacy outnumbered positive statements by 61 percent to 39 percent. His coverage was more negative than that of any other victorious candidate of either party at any stage of the primaries.

Figure 10: Trend in Tone of Trump’s News Coverage

The unfavorable tone of Trump’s coverage owed to a shift in its content. The primary victories that moved him ever closer to a delegate majority were a source of positive news. But victories in the absence of competitors are less newsworthy, opening up news time and space for other subjects. In the campaign’s final month, journalists increasingly probed Trump’s character and policy positions, framing them through the lens of Trump as a possible president rather than Trump as a striving candidate. News references to Trump’s character and policies, which in earlier stages had never accounted for even as much as 10 percent of his coverage, jumped to 19 percent of it. The tone was cutting. Negative statements outpaced positive ones by 10 to 1. Adhering to the unwritten rules of American journalism, reporters typically refrained from criticizing Trump directly, relying instead on the voices of others. No event provided a bigger opening than an early June speech in which Clinton portrayed Trump as unfit for the presidency. Virtually every major media outlet headlined the event, lacing their story with quotes from Clinton’s speech, as in this case: “Donald Trump’s ideas aren’t just different. They are dangerously incoherent. They’re not even really ideas — just a series of bizarre rants, personal feuds and outright lies.”[21]

Sanders’ victory in Indiana’s May 3 primary, which caught some pundits by surprise, gave force to his claim that he would surge in the remaining contests. And he did pick up four more states during the last month—West Virginia, Oregon, Montana, and North Dakota. But Clinton won five of the remaining contests, including those in the two largest states, New Jersey and California. Her victories secured the delegates needed to assure her nomination. Over the course of the primaries and caucuses, she had won a majority of states, a majority of votes, and a majority of both pledged and unpledged delegates.

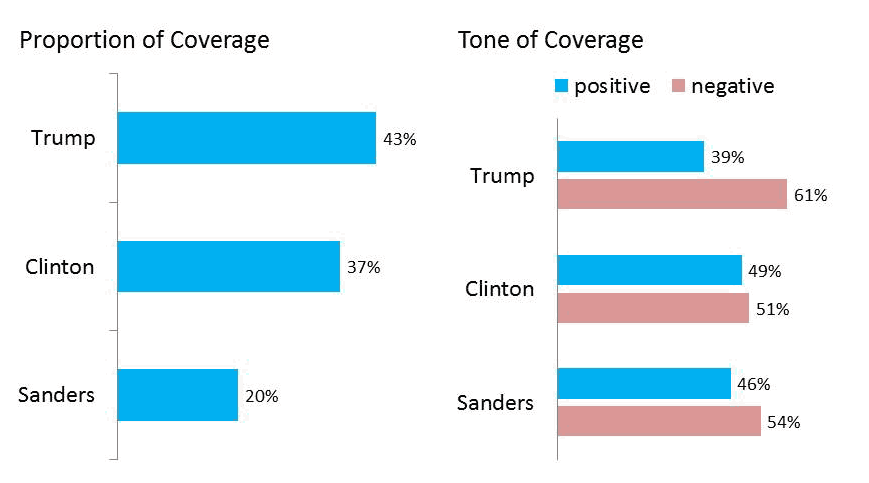

Clinton’s electoral success did not, however, result in strongly favorable coverage (see Figure 11). Positive statements about her candidacy (49 percent) were slightly outmatched by negative ones (51 percent). Sanders fared marginally worse. Negative statements about his candidacy outweighed positive ones by 54 percent to 46 percent. In terms of the volume of coverage, Sanders fared even worse, getting only about half as much news exposure as Clinton. Part of the reason for Clinton’s edge over Sanders was that Trump increasingly targeted her, which drew her into his spotlight. “Crooked Hillary” had replaced “lying Ted” in Trump’s lexicon.

Figure 11: Candidate Coverage—Final Month

Trump’s attacks on Clinton, duly reported, were part of the reason why negative statements about Clinton were as frequent as positive ones. And she continued to get mostly bad press around her character and policy positions. In the closing month, such references to her candidacy ran 10 to 1 negative over positive.

Journalists’ meta-narrative of Clinton did not change much during the primaries, nor did it differ all that much from their characterization of her candidacy in the year preceding the primaries. Clinton was portrayed as the candidate best prepared to take on the presidency—ready to lead from “day one.” That positive assessment was enmeshed in a set of less positive ones—that she represented the politics of the past and was tied too closely to big money, that she was distant and robotic, that she was less than trustworthy. Throughout the whole of the primary period, news statements about Clinton’s character were largely negative in tone—a reason that, despite her electoral success, Clinton never once had a period of favorable press comparable to what Trump, Sanders, and even Cruz enjoyed at their peak.

Part of the reason for Clinton’s edge over Sanders was that Trump increasingly targeted her, which drew her into his spotlight. “Crooked Hillary” had replaced “lying Ted” in Trump’s lexicon.

Sanders’ negative press in the final month was dominated by references to his electoral defeats and his vanishing shot at the Democratic nomination. He continued to get positive press around his character and issue positions—the only candidate to do so throughout the primary period. Sanders’ coverage during the primaries was the antithesis of Trump’s. Trump got a lot of press attention. Sanders didn’t get a lot. Trump’s positive coverage was rooted in his electoral success while his negative coverage flowed from his policies and character. Sanders’ positive coverage stemmed from his policies and character while his electoral defeats and unlikely prospect of nomination accounted for the bulk of his negative coverage.

After every presidential nominating campaign, pundits and scholars, along with more than a few journalists, say that the campaign would be better if only the press would report it differently. The assumption underlying this claim is that the press is positioned to act differently.

It’s a questionable assumption. The press is less effective as a link between candidates and voters than is sometimes believed. The problem is that the press is not a political institution. Its business is news and the values of news are not those of politics. Election news carries scenes of action, not assessments of the values reflected in those scenes. Election news emphasizes what is controversial or different about events of the past day rather than what is stable and enduring. Election news is framed in the context of winning and losing rather than what’s at stake in the choice of a president.

Journalists cannot be faulted for the system they are required to cover. They didn’t invent America’s marathon nominating process. But the structure of the nominating process is at odds with journalists’ norms and values.

This is not to say that election news is unimportant. It can enlist the voters’ interest in the campaign, keep them abreast of new developments, and make them aware of facts that would otherwise stay hidden. And a dose of election theater is a healthy thing. It can lighten the moment and get voters talking about the campaign. But insofar as voters depend on the media to formulate their mental images of the candidates, they get a picture shaped largely around the values of journalism.

Journalists cannot be faulted for the system they are required to cover. They didn’t invent America’s marathon nominating process. But the structure of the nominating process is at odds with journalists’ norms and values. This observation is not the usual complaint that the press is obsessed with the horse race. For more than a century the press has reported on who is winning and losing. What is different is that, after the nominating process was changed in the early 1970s to require states to hold a primary or caucus, the horse race was elevated to unprecedented heights. Tasked with covering fifty contests crammed into the space of several months, journalists are unable to take their eyes or minds off the horse race or to resist the temptation to build their narratives around the candidates’ position in the race.

The plot-like nature of the competitive game makes it doubly attractive. Whereas policy issues lack the day-to-day novelty that journalists seek, the game is always moving as candidates adjust to the dynamics of the race and their position in it. Since it can be assumed that candidates are driven by a desire to win, their actions can be interpreted as an effort to acquire votes. The game is a perpetually reliable source of fresh material.

Many journalists, no doubt, would argue that the issues received a lot of attention during the primary period. Most of this coverage, however, was not about the issues as such, but how they were affecting the election. Issues were reported, less as substantive policy questions, than as tokens in the strategic game, as in this case: “Donald Trump’s hard-line position on immigration is the main reason he is favored to win the Arizona Republican primary Tuesday—and lose the Utah caucuses.”[22] Much of the “issue coverage” was also in the form of what political scientist V.O. Key once called “transient squabbling”—momentary controversies that come and go, as in the case of Rubio’s remark about the size of Trump’s hands.[23]

Game-centered reporting has consequences. The media’s tendency to allocate coverage based on winning and losing affects voters’ decisions. The press’s attention to early winners, and its tendency to afford them more positive coverage than their competitors, is not designed to boost their chances, but that’s a predictable effect. As two leading scholars of mass communication once noted, “If you really matter, you will be at the focus of mass attention, and if you are at the focus of mass attention, then you must really matter.”[24] Trump’s largest jumps in national polls during the primary period came in the aftermath of his victory in New Hampshire and his showing in the Super Tuesday period, which coincided with peaks in both the volume and positive tone of his coverage. Trump’s candidacy was propelled by press coverage throughout 2015 and into the first three stages of the primary period. He might have won the Republican nomination in any case, given the confluence of factors working in his favor. But one of his assets, certainly, was his press advantage.

The tendency of journalists to construct their candidate narratives around the status of the horse race also affects the candidates’ images. Every candidate has strengths and weaknesses but the ones that come to the forefront in news coverage are the ones that fit reporters’ race-driven storylines. A candidate who is doing well can normally be expected to be wrapped in a favorable image—his or her positive attributes will be thrust into public view. A candidate who is doing less well has his or her weakest features put before the public. It is as if the runners in a 100-meter dash were stopped after 20 meters, with those in the lead placed at the 25 meter mark while those in the back placed at the 15 meter mark before the restart. That type of handicapping would be even more severe if the runners had been placed at different distances from the initial starting line, which is the case in the presidential nominating system. Iowa is better suited to some candidates than to others, as is New Hampshire. That defect, perhaps unavoidable in that the nominating race has to start somewhere, is magnified by the media’s tendency to allocate their coverage and base their evaluations on the order of finish in the opening contests.

Scholars have not closely studied the effect on voters of journalists’ “electability” claims and such claims may not directly affect a candidate’s chances. But the secondary effect of journalists’ electability judgments—the parceling out of press attention unevenly between those deemed electable and those deemed not—influences voters’ decisions. Would Sanders have benefited enough from heavier coverage in the early primaries to have had a real shot at the Democratic nomination? Probably not, but his inability to achieve a high level of press attention hurt his chances.

Game-centered reporting has consequences. The media’s tendency to allocate coverage based on winning and losing affects voters’ decisions.

In some elections, the campaign is also distorted by the media’s fascination with the story possibilities presented by one of the candidates. That was true, for example, of Barack Obama’s 2008 candidacy, John McCain’s 2000 candidacy, Gary Hart’s 1984 candidacy, and Jimmy Carter’s 1976 candidacy. Donald Trump can now be added to the list. Any such candidate gets outsized coverage. It’s not that journalists sit back and decide to put their finger on the scale in a way deliberately intended to help a candidate who captures their fancy. They are in it for the story, though the political impact is real enough.

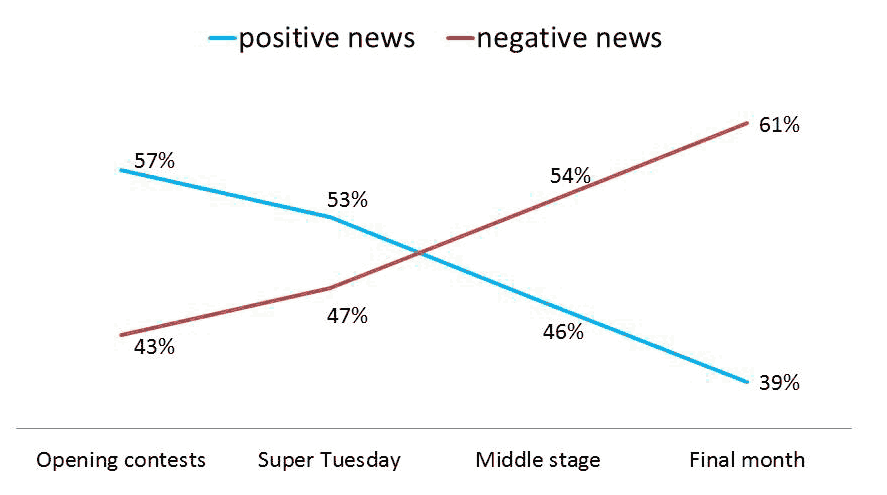

To a degree, the combination of journalistic imperatives and the campaign’s structure leads reporters into a pattern of primary election coverage that’s the inverse of what would work best for voters. Most voters don’t truly engage the campaign until the primary election stage. As a result, they enter the campaign nearly at the point of decision, unarmed with anything approaching a clear understanding of their choices. They are greeted by news coverage that’s long on the horse race and short on substance (see Figure 12).[25] It’s not until later in the process, when the race is nearly settled, that substance comes more fully into the mix. As political scientist Henry Brady noted, the “primaries force people to choose before they are ready to do so.” They learn, but most of them learn “too late.”[26]

Figure 12: Trend in Election News Topics

To a degree, the pre-primary and primary televised debates helped jump start the normally slow process by which voters come to understand their choices. The 2016 debate audiences set records for their size, and by a wide margin. That was true of both parties’ debates, but especially those on the Republican side. Trump was a drawing card the likes of which had never before been seen. Although studies of the debates’ impact on voters’ understanding of the candidates are yet to come, there is no reason to think their impact was small. But a number of debates offered more heat than light, and the heat was what made it into the headlines. And the main question that underpinned the debate analysis was not what it revealed about the candidates’ fitness for office but how it might affect their chances of winning. The “who won” narrative that drove the primary coverage also drove the debate coverage.[27]

The problems associated with press coverage of the 2016 nominating campaign are rooted in the mismatch of journalism values and the structure of the nominating process. There is little question that the nature of the 2016 campaign—Trump’s presence, particularly—brought the mismatch into sharp relief. But the broad tendencies in press coverage of the 2016 coverage are ones that exhibit themselves every four years.

[1] Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (New York: Free Press, 1965). Originally published in 1922.

[2] Quoted in Paul Taylor, See How They Run, (New York: Knopf, 1990), p. 25.

[3] Thomas E. Patterson, Out of Order (New York: Knopf, 1993), p. 127.

[4] Quoted in Thomas E. Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980), p. 44.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, p. 45.

[7] Of the figures in this report, those in this section are the most subject to interpretation. Media Tenor’s coding categories do not overlap neatly with the analytical categories in Figure 3. In developing the estimates, I first estimated the “substantive concerns” percentage, erring on the side of inclusion. I then calculated the remaining percentages by treating news references that were positive or negative in tone as game related and those that were neutral in tone as process related. Other methods of calculation would have changed the numbers somewhat but not significantly and certainly nowhere near enough to change the rank order of the three categories.

[8] Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, “Trump wins South Carolina; Bush drops out of GOP race,” The Washington Post, February 21, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-wins-south-carolina-bush-drops-out-of-gop-race/2016/02/20/16f80c9a-d655-11e5-be55-2cc3c1e4b76b_story.html

[9] Jeremy W. Peters and Michael Barbaro, “How a Debate Misstep Sent Marco Rubio Tumbling in New Hampshire,” The New York Times, February 10, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/11/us/politics/marco-rubio.html

[10] Quoted in Christopher Arterton, “Campaign Organizations Confront the Media-Political Environment,” in James David Barber, ed., Race for the Presidency (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1978), p. 11.

[11] Reuters, “Hillary Clinton Scores Narrow Win Over Bernie Sanders In Nevada Caucuses,” February 21, 2016.

[12] Jimmy Lasalvia, “This is why Hillary’s losing: The failing strategy that could cost her everything — and the Bernie Sanders ad that exploits it perfectly,” Slate, February 12, 2016. http://www.salon.com/2016/02/12/this_is_why_hillarys_losing_the_failing_strategy_that_could_cost_her_everything_and_the_bernie_sanders_ad_that_exploits_it_perfectly/

[13] Chris Cillizza, “Bernie Sanders can run for as long as he wants. But his chances of winning are disappearing,” The Washington Post, February 29, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/02/29/bernie-sanders-is-going-to-stay-in-the-2016-race-but-its-hard-to-see-how-he-wins/

[14] Manuela Tobias, “Cruz crushes Trump in Kansas,” Politico, March 5, 2016. http://www.politico.com/story/2016/03/ted-cruz-wins-kansas-220298

[15] Mark Barabak, “With a big Super Tuesday, Trump has the Republican nomination in his sights,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 2016. http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-gop-super-tuesday-20160301-story.html

[16] Alex Leary, “The rise and stall of Marco Rubio,” Miami Herald, March 11, 2016. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/election/marco-rubio/article65479847.html

[17] Rachel Weiner, “Even as Clinton wins, many Va. voters stay focused on Trump,” Washington Post, March 1, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/super-tuesday-in-virginia-clinton-trump-expected-to-win/2016/02/29/a63c1254-df22-11e5-8d98-4b3d9215ade1_story.html

[18] Bob Davis and Rebecca Ballhaus, “The Place That Wants Donald Trump Most,” The Wall Street Journal, April 17, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-place-that-loves-donald-trump-most-1460917663

[19] Evan Halper and Kate Linthicum, “Sanders Wins Indiana, Keeping His Movement Alive,” Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2016. http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-indiana-democratic-primary-20160503-snap-story.html

[20] Alex Seitz-Wald, “Sanders Gets Momentum But Gains Little From Wisconsin Win,” NBC News, April 6, 2016. http://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/sanders-gets-momentum-gains-little-wisconsin-win-n551476

[21] Meghan Keneally and Liz Kreutz, “Hillary Clinton Calls Donald Trump ‘Temperamentally Unfit’ to Be President,” ABC News, June 2, 2016. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/hillary-clinton-calls-donald-trump-temperamentally-unfit-president/story?id=39555600

[22] James Hohmann, “Trump’s Immigration Stand Expected to Help in Arizona, but Hurt in Utah,” The Washington Post, March 22, 2016, p. A15.

[23] V.O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics (New York: Knopf, 1949), p. 302.

[24] Paul Lazarsfeld and Robert Merton, quoted in William C. Adams, “Media Coverage of Campaign ’84,” Public Opinion 7 (1984): p. 13.

[25] As with the earlier figures on election news topics, those in this chart are the most subject to interpretation because Media Tenor’s coding categories do not overlap neatly with the analytical categories in the chart. In developing the estimates, I first estimated the “substantive concerns” percentage, erring on the side of inclusion. I then calculated the competitive game figures by looking at the level of coverage in each phase of the campaign given to three of Media Tenor’s categories: election campaigns, primaries, and public opinion polls. For each resulting percentage, I calculated the percentage of the coverage that had a positive or negative tone, treating this proportion as “competitive game” coverage. The results were then normed to the overall percentage of game coverage (56 percent) to derive the percentage for each stage. Other methods of calculation would have changed the numbers somewhat but would not have changed the rank order of the four stages in terms of the amount of coverage afforded the competitive game.

[26] Henry Brady, “Media and Momentum,” unpublished paper, undated. See also Henry E. Brady and Richard Johnston, “What’s the Primary Message,” in Gary Orren and Nelson Polsby, eds., Media and Momentum: The New Hampshire Primary and Nomination Politics (Chatham, NJ: Chatham House, 1987), p. 184.

[27] Based on Media Tenor’s data on debate coverage in the period January 1-June 7, 2016.

Videos

Commentary

Videos