Introduction

The staffing of the American news media has never fully reflected the diversity of the nation. For most of the country’s history, Latino and non-white journalists were not welcomed in white-run newsrooms and, through their own news outlets, produced content which shed light on issues the white press was ignoring. In the 1890s, journalist Ida B. Wells covered lynchings the mainstream news outlets would not. In the 1950s and 1960s, newspapers and television networks struggled to cover the Civil Rights era with only a rare few black journalists in their newsrooms. The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, popularly known as the Kerner Commission, was convened by President Lyndon B. Johnson against the backdrop of cities burning in what were then called “race riots.” Among the 1968 report’s broader findings, key sections criticized news coverage of race and politics, pointing out the lack of diversity in America’s newsrooms.

Half a century later, in a year filled with prominent Civil Rights era commemorations including the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., questions persist about newsroom staffing. The American Society of News Editors’ stated goal in 1978 to steadily bring newsroom diversity numbers to parity with national averages has not materialized,[1] despite the large demographic shift in America’s racial and ethnic makeup.[2] The ASNE’s annual newsroom diversity survey shows that Latino and non-whites made up 12 percent of newspaper editorial staff in 2000,[3] and by 2016, that had edged up to only 17 percent.[4] The United States population is currently 38 percent Latino or non-white, more than double the percentage of newsroom representation.[5] In 2016, women were 51 percent of the U.S. population, but made up only 38 percent of newspaper editorial staff. The Women’s Media Center found that, “at 20 of the nation’s top news outlets [in 2017], men produced 62.3 percent of news reports analyzed while women produced 37.7 percent of news reports.”[6]

Teri Hayt, ASNE’s executive director (and the first woman to hold the position in the organization’s 90-plus year history) said the numbers “have not moved that much” in recent years. As for why publishers and editors should care about diversity, she stated simply, “You should care because you’re losing audience share [if you don’t].” Melissa Harris-Perry, the Maya Angelou Presidential Chair at Wake Forest University, who is also the founder of the Anna Julia Cooper Center and the former host of the Melissa Harris Perry show on MSNBC, sees the issue as one of equity and balance. “The very idea of having to answer the question, ‘Why does it matter for them [i.e., journalists of color] to be there?’ means all the space should be owned by white men. People who live in bodies that are marginalized don’t have to bring anything other than their excellence or mediocrity to the table, because that’s what white people do.”[7]

This paper begins with a focus on the Kerner and Civil Rights era; progresses into research on the diversity of 2016 political news teams; and ends by exploring what might be done to create more diverse newsrooms. How have newsrooms changed, or failed to change? How prepared, willing and able are newsrooms to learn from their own behavior in a politically turbulent time? And what does this all mean for media equity, now and in the future?

The Kerner Commission: Lessons and Legacy

This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.

Discrimination and segregation have long permeated much of American life; they now threaten the future of every American.

This deepening racial division is not inevitable. The movement apart can be reversed. Choice is still possible. Our principal task is to define that choice and to press for a national resolution.[8]

Those are the words of the Kerner Commission, which was chaired by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. and tasked with exploring why black urban neighborhoods were imploding in 1967, most prominently in Newark and Detroit. The document outlined the role of the federal government in creating and maintaining the economic segregation of predominantly black urban areas (described in the Kerner report as “the ghetto”). And it noted the failures of the American media to provide the newsroom diversity and type of coverage that might be part of a constructive response.

Newsroom diversity can contribute to the thoroughness of coverage, just as a lack of diversity can create massive blind spots.

The Kerner Commission report pointed out failures in equitable and thorough news coverage, not just in newsroom staffing. “Our second and fundamental criticism,” it reads, “is that the news media have failed to analyze and report adequately on racial problems in the United States, and, as a related matter, to meet the Negro’s legitimate expectations in journalism.”[9] Of particular note was the idea that all citizens have a right to “legitimate expectations” that communities (including but not limited to racial groups and geographic regions) will be covered thoroughly and fairly.

Newsroom diversity can contribute to the thoroughness of coverage, just as a lack of diversity can create massive blind spots. In 2009, journalist Kai Wright penned a piece for the American Prospect detailing how his parents lost their home after failing to find a way to refinance their sub-prime loan to avoid balloon payments.[10] As he points out:

In 2006, African American borrowers at all income levels were three times as likely to be sold sub-prime loans than were their white counterparts, even those with comparable credit scores. The Pew Hispanic Center reports that 17.5 percent of whites took out sub-prime loans but that 44.9 percent of Hispanics and 52.5 percent of African Americans took out sub-prime loans. Blacks like my mom, who could qualify for conventional loans, were targeted for sub-prime ones, which generated higher fees for the lender and higher costs and risks for the borrower.

Wright subsequently described how the sub-prime mortgage crisis hit black and brown homeowners first, and how, if newsrooms had been expansive in their coverage of mortgage lending in communities of color, they might have more quickly spotted the looming, nationwide sub-prime crisis. Did Wright cover the sub-prime crisis because of his parents, or because he is black and aware of the banks’ impact on black communities, or because he is an enterprising reporter? Although it’s impossible to say for sure, Wright’s reporting illustrates the potential power of diversity in improving news coverage and reporting. As we look back at the “legitimate expectations” for equitable news coverage in the Kerner Commission report, it’s hard to imagine meeting those expectations without the greater presence of women and people of color in newsrooms.

In “Not an Anomaly,” British data journalist Asama Day writes:

Homogeneity is a huge issue in an industry which aims to inform an increasingly diverse society…Diversity is more than skin colour or religion and should emulate society by incorporating gender, age, social background, sexual orientation and disability. Newsrooms should aim to reflect the world they report about and the audiences they serve—while still retaining the values of hiring the best person for the job.

At the same time, Day notes that it’s important that reporters of all backgrounds develop competencies in covering a multi-ethnic world: “While issues relating to race and discrimination are important and must be reported on, data journalists of all races, ethnicities, religions and backgrounds should be able to report on them and shed a light on them.”[11]

Richard Prince, a longtime journalist who writes a media and diversity column titled “Journal-isms,” echoed the notion that every reporter can contribute to equitable news coverage. “I’m seeing more people who are not people of color writing about racial issues,” he said.[12] He cites the 2017 Pulitzer Prize-winning story by reporter Sarah Ryley,[13] who is white, about police evictions of New Yorkers in minority neighborhoods who haven’t committed crimes. “What the Kerner Commission was saying was that the general population was not finding out what was going on in the black community,” Prince added, which not only was, “frustrating to black people,” but also harmful to civil society generally.

Following the publication of the Kerner Commission report, journalists of color seized upon the findings and founded new organizations including the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) to help expand newsroom opportunities. In an article for the Columbia Journalism Review, NABJ co-founder Paul Delaney stated that, following the Kerner era:

A group of us formed the National Association of Black Journalists in 1976, with the aim of prodding our profession to thoroughly integrate its newsrooms as soon as possible. At the time, our enthusiasm was extremely high, we felt that we were onto something big and good, that we were on the right side of history…We were so naively optimistic back then.

Their optimism was misplaced. Delaney noted that, “Several veteran reporters, when requested, refused to assist us and act as teachers and mentors to young minority hires and trainees.” Nevertheless, he said, “My career at The New York Times switched from reporting and editing to helping the company to become less white and more inclusive. And it worked. For a while.” His conclusion, though, was pessimistic. “To say that I’m disappointed today by the entire situation, not only at The New York Times, but in my chosen profession, is an understatement. However, truth be told, I’m not surprised at all. It’s still a racial and racist thing the nation cannot seem to take hold of nor shake, after all these centuries.”[14]

New Threats

At the on-the-record Unity Journalists for Diversity gathering in April 2017, attendees included representatives of major news outlets including The New York Times, those from organizations including ASNE and the National Association of Black Journalists, and academics working on diversity in journalism. Much of what emerged in conversation considered the heightened risks in covering politics during an era of internet trolls and harassment. There is pain being inflicted outside the newsroom, from harassment by interview subjects and hostile news consumers; conflict and sometimes harassment in newsrooms; and a recognition that covering race in and of itself can be traumatic. Jesse Holland, who covers race and ethnicity for the Associated Press, spoke about how covering racially-motivated killings time and again takes an emotional toll. There’s also the question of what different people, again, both inside and outside of the newsroom, expect from reporters of color. Holland and Simon Moya-Smith, an independent Native American journalist, addressed the special burden borne by journalists of color. They are sometimes seen as double agents, working both for their ethnic communities and for journalism broadly—sometimes pleasing neither.

Discussions at the conference questioned whether the comfort and safety of white reporters was placed above that of reporters of color. Nicki Mayo of the National Association of Black Journalists spent the 2008 election based in Appalachia. While completing a mix of political and general-interest reporting, she found herself forcibly dragged into a men’s bathroom during NASCAR races in Bristol, Tenn. She also spoke of interning for an outlet in her hometown of Baltimore and being asked to accompany a young white reporter into a black neighborhood. She pointed out that no one had given her an escort when she covered white working-class communities in Appalachia. It should be noted that during the conversation, several female reporters, including a Muslim woman wearing a headscarf, stated emphatically they did not want to be barred from taking high-risk assignments by their editors.

The risks of reporters being targeted for their identities rose during the 2016 election cycle. Carolyn Ryan supervised the New York Times’ political coverage during the election and in February of that year was promoted to assistant editor in charge of journalist recruitment.[15] “Anyone believed to be Jewish was attacked on Twitter,” she said, citing the harassment of reporter Jonathan Weisman. Twitter “blew us off,” she said of the Times’ initial attempts to incite the platform to intervene. Another Times reporter was doxed after writing a piece about Senator Marco Rubio’s finances. He was harassed for being gay, and information about his husband and his apartment were made public. Elsewhere, after an Indian-immigrant engineer in Kansas was killed by a gunman who yelled, “Get out of my country,”[16] Rhonda LeValdo, a Kansas City broadcast host and producer, decided to heed an anonymous threat she received by mail. “We’re living in a different time and I should not let this go,”[17] she explained at the Unity gathering.

Mizell Stewart is the head of news talent and partnerships at Gannett and USA Today Network, is the former president of American Society of News Editors, and is now the president of the ASNE Foundation. In the current environment, Stewart said, journalists need to turn to each other. “We have an administration that is playing asymmetrical warfare against the press, and it’s incumbent among us as journalists to band together to a degree we are not usually comfortable with. How do we as journalists—dare I say, as patriots—work more collaboratively to push back against this idea that we have somehow become the enemy of the American people?” For the reporters who covered and continue to cover politics, the hostility toward the press and the targeting of personal identity is taking its toll.

Related to this is the question of whether the news media’s incessant replay of Trump’s xenophobic attacks incited racial and ethnic bias in white voters. A Gallup study found that racial resentment, which had dropped during the latter years of the Obama presidency, rose during and after the 2016 election.[18] The belief that Latinos and non-whites are given special privileges in everything from employment to social service systems like Medicare was a major predictor of Trump support during the GOP primaries.[19] Political scientist Thomas Wood of Ohio State University analyzed data from the 2016 American National Election Study and found, that since 1988 there hasn’t been such a clear correspondence between vote choice and racial perceptions.[20]

In the aftermath of the election, some reporters have written or spoken publicly about the issue of race/gender/and otherness on the campaign trail. The Washington Post’s Robert Samuels, a national political reporter who is black, described a time he was mistaken for a protester at a Trump rally:[21] “As the police pushed me out of that rally, people started calling me ‘monkey,’ a person tried to trip me, they shouted, ‘all lives matter,’ at me. It was one of the most frightening experiences that I’ve ever had as a reporter,” he said. Candace Smith of ABC wrote about being “the only black reporter who covered Trump in the field (except for the last week of the election),” a beat she was assigned after Jeb Bush dropped out of the race in February 2016.[22] She and fellow journalists—especially those perceived to be Jewish, she noted—were targeted by protesters at rallies. She was harassed on the basis of both race and gender, adding, “On Twitter, I’ve been called a ‘n—–,’ a ‘c—‘ and, at times, a combination of the two.” Her family feared for her safety. “Confederate flags seemed omnipresent. I saw them in Pittsburgh, in North Carolina, in San Diego and in Florida,” she continued. “When I noted the flags, people on Twitter would ask why I was so obsessed with race. But race—as a black woman in America—is something so many of us are acutely aware of. It is the lens through which everything is filtered.”[23] In newsrooms across the country, Latino and non-white reporters brought the increasingly hostile racial environment on the campaign trail to the attention of their editors, but based on both published reports and interviews offered on background for this paper, their warnings were largely ignored.

Press Diversity and the 2016 Election

The 2016 election season demanded much of journalists, including a deep knowledge of this nation’s diverse communities and constituents—by race, gender, class, region and religion, among other factors. Most major news outlets and news teams failed to anticipate the unusual nature of the election, which does not at its base invalidate their work. However, post-election assessments have not included systematic analyses of who was chosen to cover the campaign.

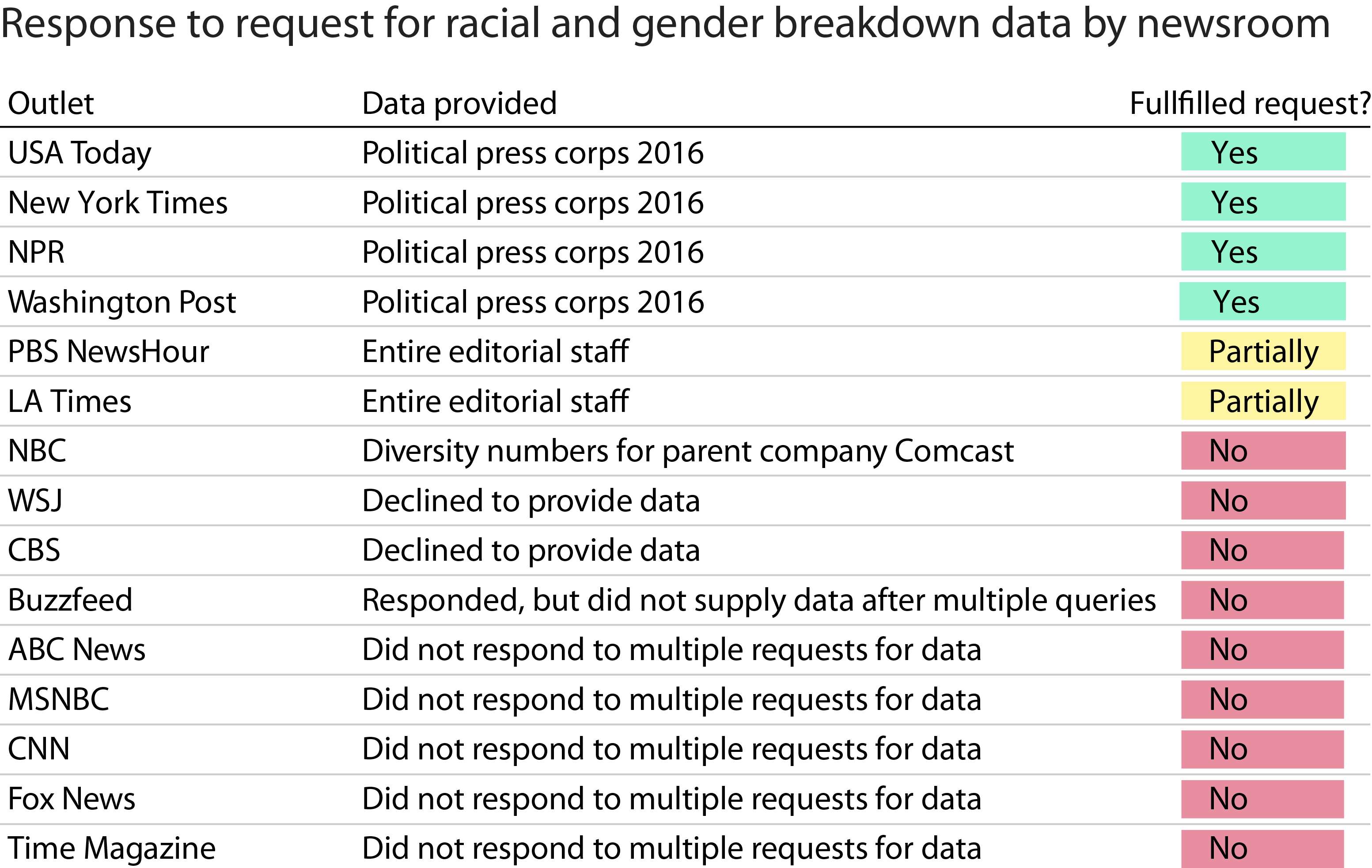

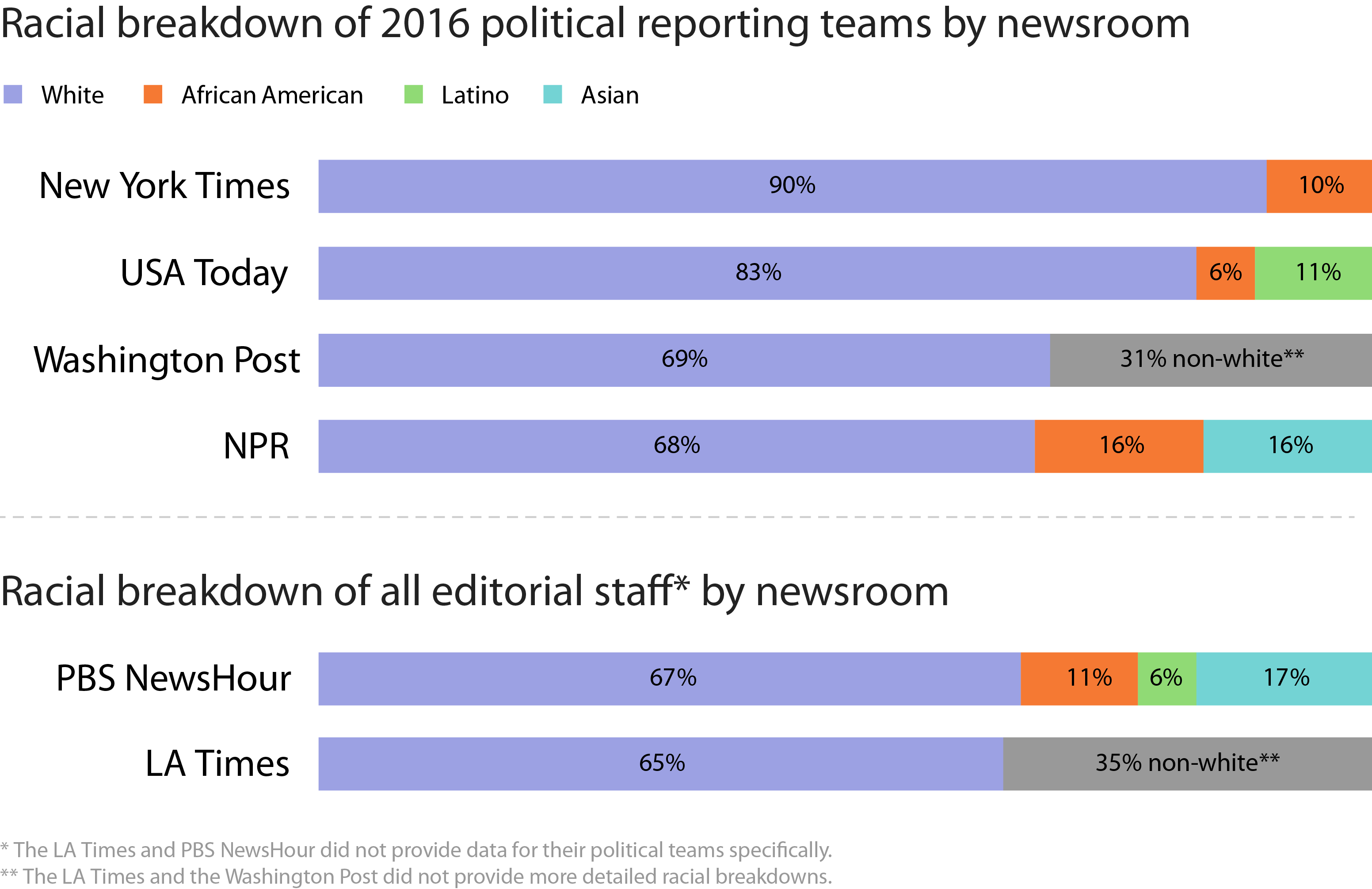

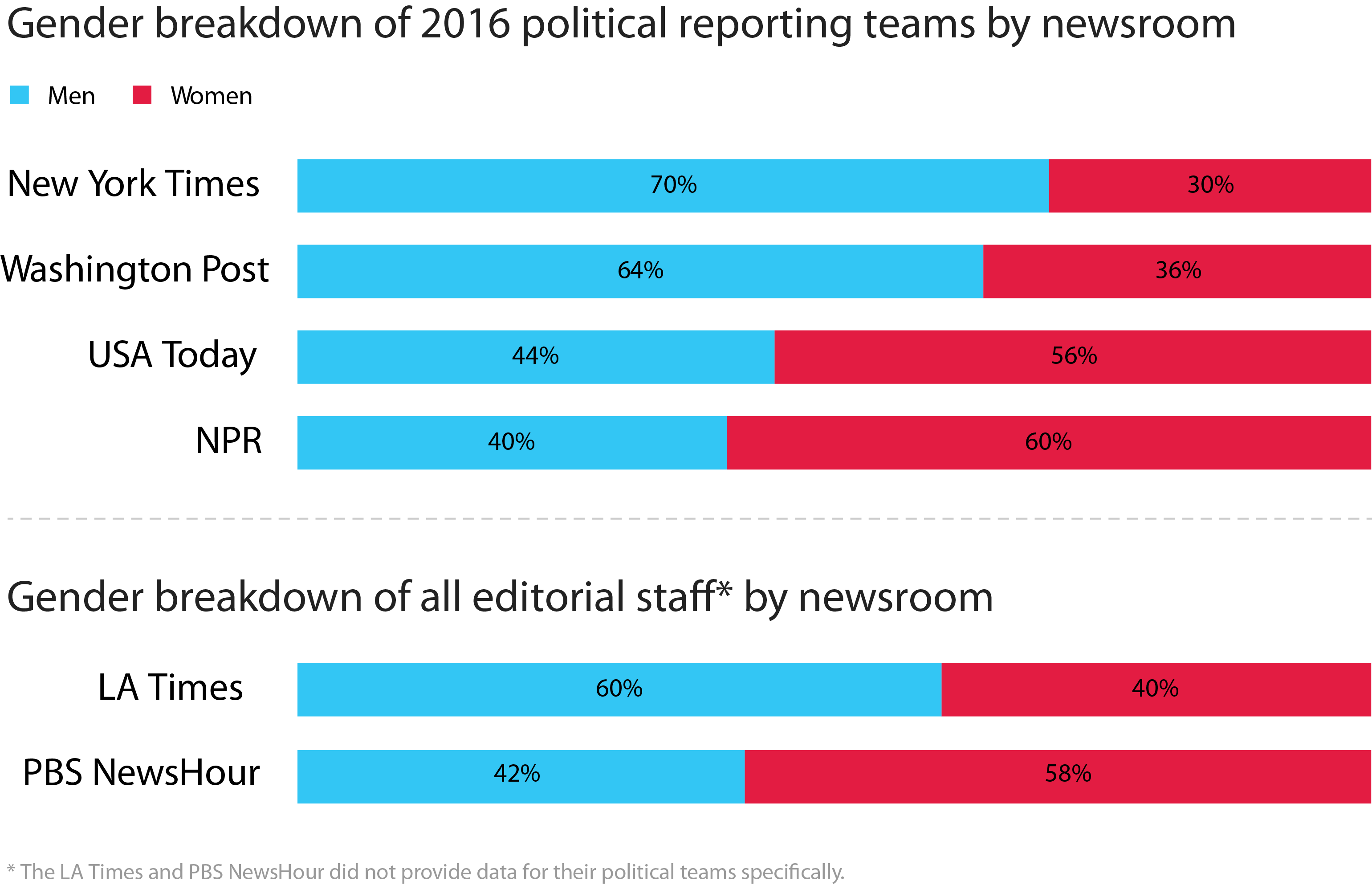

I contacted 15 major news outlets for information about their political press corps, expecting they would readily provide it. That was not the case. Despite repeated inquires, fewer than half—only USA Today, The New York Times, NPR and The Washington Post—provided the requested data. PBS NewsHour and the Los Angeles Times provided numbers for their entire editorial staff, but not political reporters. NBC provided numbers for parent company Comcast, without a breakdown of newsroom staff. Other outlets declined to provide data—or even respond.

It was even difficult to get reporters and editors to talk about the issue. Often, they would do so only if they were on background or off the record, which is curious given journalists champion transparency when it comes to other institutions. That raises the question of whether journalists are afraid of retaliation if they speak on the record about the race and gender dynamics of their reporting teams. The #MeToo era has certainly shown that what goes on inside the newsroom is not always apparent from the outside.

That said, a few newsrooms were quick to respond to my query, and also to comment in depth. Within half an hour of my request, USA Today Washington Bureau Chief Susan Page responded with their data. USA Today’s 2016 campaign coverage staff had 10 women and eight men, and, among those, two Latino and one African-American reporter. Page offered an interview with Lee Horwich, the managing editor for government and politics, to discuss their approach to both staff diversity and regional representation.[24] Said Horwich, “Since we’re all over the country we have communities we need to serve that are very different from each other: the Detroit Free Press, the Des Moines Register, the Arizona Republic.” He stated that this regional diversity gives the network eyes and ears on the ground and “allows us to present a level of understanding that can reflect the issues that are important now and in 2020.”

Horwich added that USA Today’s staffers experienced the same harassment during the 2016 election that other reporters did, and they addressed questions like how to keep reporters safe without constraining assignments on the basis of gender or race. “We had reporters out with candidates, in particular the Trump campaign, who were harassed for being reporters, for being women, for any number of reasons,” he said. “It was a very difficult and almost unprecedented situation.”

“I think that 2020 is going to pose a huge challenge for political journalists,” Horwich said. “I think that it is vital that we have an understanding of the diversity of staff that we need to approach these problems. But not just that, regardless of race/gender/ethnicity of journalists, we need to be reflective of the diversity of the electorate and of the country as a whole, and explain and understand what those people are saying and demanding.” USA Today began assessing its 2020 staffing and editorial needs right after the election. “Four years seems like a long time. It isn’t.”

Looking for Solutions

Newsrooms often operate under the assumption that major civic organizations—government, nonprofits, business—should be transparent. Yet journalism does not always hold itself to the same standard.

Both news industry staff diversity and media equity require more study, but particularly, more action. Dedicated individuals both within and outside of the news industry have pursued a variety of mechanisms to align newsrooms with the needs of a demographically changing America. But newsroom management, as illustrated by NABJ co-founder Paul Delaney’s example, has not always welcomed change…or a significant influx of reporters of color.

Greater transparency would help. This is particularly true of newsrooms, who could offer metrics about their own staffing patterns and the decisions behind them. Newsrooms often operate under the assumption that major civic organizations—government, nonprofits, business—should be transparent. Yet journalism does not always hold itself to the same standard. Foundation funding only directly affects a limited number of newsrooms, though some foundations fund for-profit institutions as well as nonprofit ones. When philanthropic organizations become involved, they have the power to demand transparency. Transparency, however, doesn’t mean simply offering metrics to funders, but also revealing them publicly to researchers and general audiences online, in print and in annual reports.

There are steps that could be taken to improve transparency. For instance, the Pulitzer, duPont and other major news prizes could require public disclosure of diversity metrics as a qualification for acceptance of the prize. This would broadly affect both the for-profit and the non-profit media outlets that compete for these awards.

Journalists themselves can also work to change the industry. In 2016, award-winning New York Times investigative reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting. Its mission is to increase the hiring and retention of investigative reporters and editors of color, and to educate news organizations about the ways diversity can increase the efficacy and impact of investigative reporting. Hannah-Jones and the other co-founders found the investigative reporting conferences they attended to be lacking in diversity. In an email interview, she stated:

Investigative reporting is the most important work that journalists do in a democracy, yet these premier and critical jobs are still almost uniformly filled by white journalists. That’s because newsrooms reflect the same racial hierarchies as the rest of society. The more prestigious a job is, the more skills it requires, the less likely people of color are to get the mentoring, training and opportunities to take on those jobs. Why does this glaring whiteness in investigative reporting matter? Because it means that stories of abuse, neglect and wrongdoing that impact millions of Americans are simply not getting covered. Diversity matters not for some politically correct, feel-good reason, but because diverse newsrooms unearth more stories and have access to more communities.[25]

Hannah-Jones noted that in the first month of the Ida B. Wells Society’s work, more than 600 journalists signed up to be members. “We intend to provide the type of high-quality mentoring and training that will make it impossible for newsrooms to say they cannot find qualified applicants. Within a few years, we hope to have a cohort of journalists that will allow us to call out these excuses because we will know there are qualified applicants—because we will have trained them ourselves,” she said.

Further, journalists might also follow the money. Newsroom discrimination settlements requiring nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) are an opportunity for investigative reporters to examine the fiscal and ethical practices of newsrooms. The work of New York Times reporter Emily Steel helped end the Fox News career of Bill O’Reilly,[26] and reshaped Fox News after revealing it had paid tens of millions of dollars in settlements to women in his case and that of network chief Roger Ailes.[27] Still, there has not yet been a major journalistic examination of payments by news outlets to settle cases involving race, ethnicity, age and sexual orientation. An effort by ProPublica to crowdsource NDAs may provide further information.[28]

Conclusion

In retrospect, the Kerner Commission report seems almost hopeful. Although it outlines a grim problem, it presents its issues clearly and with the expectation that the rallying cry will produce action. Today, the lack of urgency, resolve or both to address issues of journalistic diversity and equity means newsrooms must be prodded into action. The words of the Kerner Commission remind us why action is necessary. To re-frame their sentiments for our industry and our times: Our newsrooms are moving towards two different ethical and functional frameworks: one which views the lack of racial and gender equity as inconsequential, and one which realizes the American news industry is not a functional meritocracy. Work remains to be done. This deepening division is not inevitable. The movement apart can be reversed. Choice is still possible. Our principal task as journalists is to define that choice and press for accountability, remedy and resolution in our newsrooms and industry.

Acknowledgments

I would like to give my deepest thanks to the Shorenstein Center and its staff, particularly Director Nicco Mele, Professor Thomas Patterson, Nancy Palmer and Nilagia McCoy. In addition, great thanks go to researcher Emily Moore, editor Kelsey Kudak, and Ella Koeze, who designed the graphics.

Endnotes

[1] “Diversity,” American Society of News Editors, accessed May 7, 2017. http://asne.org/diversity.

[2] “QuickFacts: United States,” United States Census Bureau, accessed May 6, 2017. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/

[3] “2000 Census,” American Society of News Editors, accessed May 6, 2017. http://asne.org/content.asp?contentid=172

[4] “2016 Survey,” American Society of News Editors, accessed May 6, 2017. http://asne.org/content.asp?contentid=447

[5] “QuickFacts: United States. Population Estimates, July 1, 2016,” United States Census Bureau, accessed May 8, 2018. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045216

[6] “The Status of Women in the U.S. Media 2017,” Women’s Media Center, accessed May 6, 2017. http://wmc.3cdn.net/dcdb0bcb4b0283f501_mlbres23x.pdf

[7] Harris-Perry, Melissa. Interview by Farai Chideya. Telephone interview, March 6, 2017. http://melissaharrisperry.com/#professor

[8] Glass, Andrew. “Kerner Commission report released, Feb. 29, 1968.” Politico, February 29, 2016, accessed May 9. 2017. https://www.politico.com/story/2016/02/kerner-commission-report-released-feb-29-1968-219797

[9] United States. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, February 29, 1968, accessed May 6, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=d2t2AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA201&lpg=PA201&dq=%22National+Advisory+Commission+on+Civil+Disorders%22+%22cHAPTER+15%22&source=bl&ots=dKw_MAUwxe&sig=CzpDNF4qxwGQoVAaowegbbgRDvQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjTwKSskdnSAhUB8CYKHaHUBJU4ChDoAQgZMAA#v=onepage&q=%22National%20Advisory%20Commission%20on%20Civil%20Disorders%22%20%22cHAPTER%2015%22&f=false)

[10] Wright, Kai. “The Assault On The Black Middle Class,” The American Prospect, June 26, 2009, accessed May 6, 2017. http://prospect.org/article/assault-black-middle-class

[11] Day, Aasma. “Not an Anomaly: On Diversifying Data Journalistm,” The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, November 6, 2017, accessed May 8, 2018. https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/blog/2017-11-06/my-experience-is-not-an-anomaly-we-need-to-diversify-data-journalism-and-all-newsrooms.

[12] Richard Prince. Interview by Farai Chideya. Telephone interview, April 21, 2017. http://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/richard-prince

[13] Ryley, Sarah. “The NYPD Is Kicking People Out of Their Homes, Even If They Haven’t Committed a Crime,” ProPublica, February 4, 2016, accessed July 6, 2017. https://www.propublica.org/article/propublica-new-york-daily-news-pulitzer-public-service-nuisance-abatement.

[14] Delaney, Paul. “Everyone Genuinely Seems to Care. Collectively, Not Much Changes,” Columbia Journalism Review, February 27, 2017, accessed May 8, 2018. https://www.cjr.org/first_person/diversity-new-york-times-paul-delaney.php

[15] Ember, Sydney. “New York Times Names Editor To Oversee Recruitment,” The New York Times, February 16, 2017, accessed May 6, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/16/business/media/new-york-times-editor-recruitment-carolyn-ryan.html

[16] Berman, Mark and Samantha Schmidt, “He Yelled ‘Get Out of My Country,’ Witnesses Say, and then Shot 2 Men from India, Killing One,” The Washington Post, February 24, 2017, accessed May 6, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/02/24/get-out-of-my-country-kansan-reportedly-yelled-before-shooting-2-men-from-india-killing-one/?utm_term=.8d7957f899be

[17] “Rhonda LeValdo,” LinkedIn, accessed May 6, 2017. https://www.linkedin.com/in/rhonda-levaldo-36556713/

[18] Bird, Robert and Frank Newport. “White Racial Resentment, Before, After Obama Years,” Gallup, May 19, 2017, accessed May 8, 2018. http://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/210914/white-racial-resentment-before-during-obama-years.aspx

[19] Tesler, Michael and John Sides, “How Political Science Helps Explain The Rise of Trump: The Role of White Identity And Grievances,” The Washington Post, March 3, 2016, accessed May 6, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/03/03/how-political-science-helps-explain-the-rise-of-trump-the-role-of-white-identity-and-grievances/?utm_term=.0a0fc040f0d8

[20] Wood, Thomas. “Racism Motivated Trump Voters More than Authoritarianism,” The Washington Post, April 17, 2017, accessed May 8, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/04/17/racism-motivated-trump-voters-more-than-authoritarianism-or-income-inequality/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.b820071abf49.

[21] Cohen, Alex and Austin Cross, “People called me ‘monkey’: Journalists covering the campaign face insults, threats,” SCPR.org, October 25, 2016, accessed May 6, 2017. http://www.scpr.org/programs/take-two/2016/10/25/52832/people-called-me-monkey-journalists-covering-the-c/.

[22] Stokols, Eli, “Jeb Bush drops out of White House race,” Politico, February 20, 2016, accessed May 10, 2018. https://www.politico.com/story/2016/02/breaking-news-jeb-bush-is-suspending-his-presidential-campaign-219564

[23] Smith, Candace. “Reporter’s Notebook: What it Was Like as the Black Journalist Who Covered Donald Trump,” ABC News, November 9, 2016, accessed May8, 2018. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/reporters-notebook-black-journalist-covered-donald-trump/story?id=43425854

[24] Horwich, Lee. Interview by Farai Chideya. Telephone interview, April 14, 2017.

[25] Hannah-Jones, Nikole. Interview by Farai Chideya. Email interview, April 14, 2017.

[26] Menza, Kaitlin. “Meet the Woman Who Took Bill O’Reilly Down.” Marie Claire, April 27, 2017, accessed May 6, 2017. http://www.marieclaire.com/culture/a26757/emily-steel-bill-oreilly/

[27] Farhi, Paul. “$20 Million Settlement and a Host’s Abrupt Exit Add to Fox’s Summer of Discontent,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2016, accessed May 7, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/former-fox-host-gretchen-carlson-settles-sexual-harassment-lawsuit-against-roger-ailes-for-20-million/2016/09/06/f1718310-7434-11e6-be4f-3f42f2e5a49e_story.html?utm_term=.fa7f50b7b7ef

[28] Tobin, Ariana. “Did Your Employer Ask You to Sign Away Your Right to Talk? We Want to Know About It,” ProPublica, May 4, 2018, accessed May 8, 2018. https://www.propublica.org/getinvolved/nondisclosure-agreements-employer-secrecy-nda