To get the weekly Information Disorder newsletter direct to your inbox, subscribe here.

Warren DNA Confusion

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s ancestry video was designed to extinguish the lingering allegations against her, but instead appears to have fanned the flames of mis- and disinformation. When the Massachusetts Democrat released her DNA results on Monday, the backlash on social media reflected a classic case of information disorder.

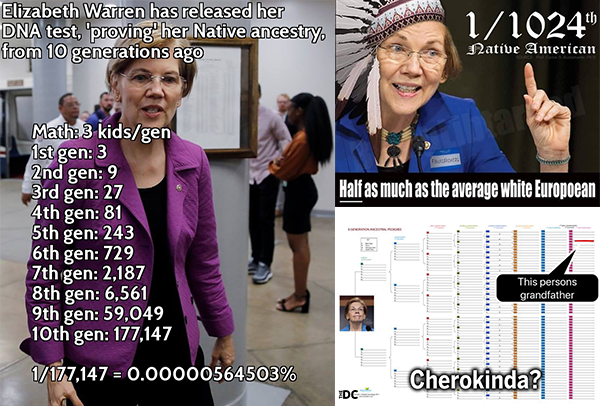

The central genetics finding, that Warren has DNA from a Native American ancestor six to ten generations back, bred significant confusion and amateur analysis. Online debates raged over the correct percentages required to be considered Native American in the U.S., confusion reigned about the nature of the DNA test itself and how to interpret the results and the numbers provided fodder for digital mockery of the senator.

Memes about the data demonstrate that not everyone can agree on the meaning of the statistics. Many cite “1/1,024th,” which excludes the higher likelihood of 1/64 found in the test results. Others interpret the lower probability as “1/512th.” When visuals portray these fractions graphically without the higher number, viewers do not have the critical information to interpret the significance. In one example the math inexplicably uses 3 people instead of 2 for each generation leading to the incredible probability of 1/177,147 instead of 1/1,024.

We have identified five distinct social media narratives that emerged following the release of the video and DNA test results. Two of these narratives — racial slurs and questions about the validity of her DNA test — drove the bulk of the immediate conversation about Warren on social media.

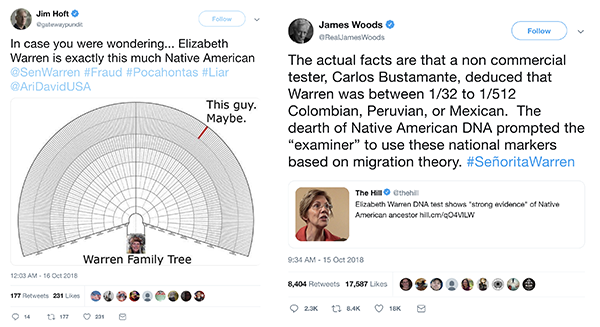

The racial-slur narrative uses popular hashtags like #SeñoritaWarren, #Pocahontas, #Fauxcahontas and #Liarwatha. These kinds of hashtags accounted for more than one-third of the conversation one day after the release. In effect, these terms perpetuate the kind of slur that Trump has used repeatedly.

An equally prominent narrative at roughly 35 percent, is the conversation about data validity. Debates focused on the significance of the probabilities, the reliability of these kinds of DNA tests and scientific conclusions based on the results.

The other three narratives, while less significant in social media volume, suggest ways in which discourse around Warren’s test results could evolve. The first of these three narratives refer to Warren as committing a “fraud” or conducting a “scam,” a second one rejects the attacks on her as simply another instance of “birtherism,” and a final, much less prevalent theme, portrays Warren’s claims of Native American heritage to be “cultural appropriation.”

Our preliminary takeaway is that although Warren took this step to try to clarify and resolve the issue ahead of a potential presidential run, this release may actually trigger more disinformation and manipulation rather than contain it.

#himtoo

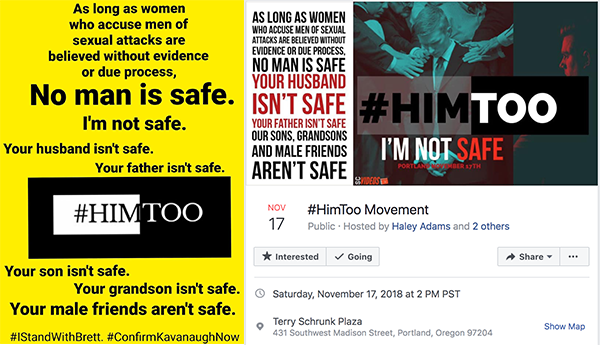

In the internet skirmishes that followed the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation process, a notable theme gained significant traction: the array of memes, statements, and discussion forums re-casting men as potential victims. #himtoo entered the mainstream discourse with the public disagreement between a Navy veteran and his mother. She tweeted that her son had stopped dating solo because of the current #metoo climate; he responded by gently refuting her comment, and in the same tweet he rejected the #himtoo movement itself. He pledged: “I respect and #BelieveWomen,” and a viral social media sensation ensued.

As a hashtag, #himtoo has been around almost as long as #metoo — perhaps longer, and with a variety of meanings:

- Arguing that Trump should also be held accountable for his own alleged past behavior

- Chiding or supporting public figures facing allegations

- Airing stories of men who have been victims of sexual assault / harassment

In the days leading up to Christine Blasey Ford’s Sept. 27 testimony, engagement surged for memes and posts employing slogans such as “#himtoo: my son, my brother, my husband” and variations on the theme that mothers should be “terrified” of false sexual assault accusations.

The meme we could identify with the most engagement had more than 250,000 shares on Facebook, with the headline “No man is safe.” Similar themes appeared across every social media platform using the visual style of Turning Point USA’s red, white and blue memes and Occupy Democrats black and yellow theme.

The #himtoo hashtag has since been employed by the nationalist Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer, which have called for a #himtoo rally in Oregon in November. Past rallies by these groups have led to violent conflicts with anti-fascist counter protesters.

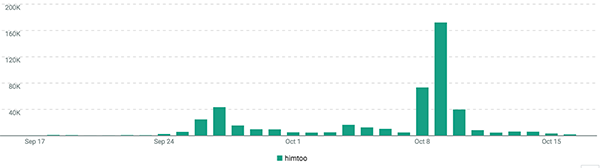

An early meme from Sept. 22 combined #himtoo and the vote on Kavanaugh directly. The meme spiraled in part by associating with the hashtag of the Republican Party’s #walkaway campaign, which encourages frustrated Democrats to walk away from their party (“In Kavanaugh’s eyes I saw my Father” #Himtoo #walkaway” – YouTube – 10/01/18 – 43,025 views). Trump further fired up social media on this issue with his comment on Oct. 2 that “this is a very scary time for young men in America” because of the threat of false accusations. Social media mentions of #himtoo also jumped on Oct. 4, the day the FBI concluded its investigation.

When #himtoo made the mainstream with the Navy veteran’s response to his mother, the online conversation flipped to criticism of the #himtoo hashtag — increasing attention to the concept just as it looked to be fading. Several spoofed memes riffing on the veteran’s mother’s post also circulated. Tweets with the #himtoo hashtag soared from 2,200 on Sept. 24 to 125,800 on Oct. 8. With all of these #himtoo spinoffs, the theme seems to have maintained substantial momentum after Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

Happy 4chan-o-ween

Some users on 4chan are promoting Halloween-themed campaigns that they would like to see publicly criticized as devilish. One meme is couched as an anti-Nazi appeal to parents — that its creators actually hope will generate more attention to Nazi issues to a point where no one can escape it.

If huge numbers of people share the meme, in the view of this 4chan argument, Nazi symbols will get far more oxygen, in effect generating publicity for these normally shunned symbols.

One participant writes: “That’s the idea … to create so many things supposed to be nazi symbols that it becomes impossible to target anything in a effective manner.”

It seems to be getting some traction: A Twitter search of “#NoNaziHalloween” reveals many posts with the same images and hashtag found in the 4chan thread.

And consider this 4chan Halloween approach:

A campaign organized online by 4chan users called “it’s okay to be white” kicked off on Halloween this past year. They put simple posters around schools and busy locations. Later in the year, another version of the campaign spread index cards with the “it’s okay to be white” slogan on one side and links to neo-Nazi, fascist and alt-right websites on the reverse in tissue boxes at Target stores across the nation.

Another phase is again planned for Halloween; supporters have been told to follow strict guidelines to keep the optics acceptable. The stated goal is to gain mainstream media attention. Many 4chan users delight in any mainstream media coverage, positive or negative.

What We’re Reading

- Facebook announced that it will take action against misinformation about voting detailed by Reuters.

- The Verge has a new project that tracks hateful users’ activity on Twitter.

- Craig Silverman proved no viral stone should be left unturned when he decided to relay the facts on a viral post about a barefoot runner.

- If you think disinformation is bad in the U.S., check out the New York Times’ assessment of the problem of fictional news in the Philippines and Facebook’s response.

- Wired’s Emma Gray Ellis had this early and detailed assessment of the #himtoo campaign’s evolution, including its support for Kavanaugh.

- Reporter Jane Lytvynenko’s case study, told in a few tweets, on the hoax saying Alan Greenspan had died. H/t Poynter

- The Guardian reports on a speech by the director general of the BBC, Tony Hall, making the case for avoiding the term “fake news” because it’s been misappropriated by repressive regimes.

- Politico is asking readers to crowdsource false or manipulated information, which will be shared in a publicly accessible database. The New York Times recently launched a similar project.