The views expressed in Shorenstein Center Discussion Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University.

Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important issues and challenges in media, politics and public policy. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Use is governed by the Harvard Kennedy School and Shorenstein Center Open Access Policies.

Download a PDF version of this paper here.

Introduction: Trump, and More Trump

During every stage of the 2020 presidential campaign, Donald Trump was the center of attention on the nightly newscasts of CBS and Fox News. The pattern had started much earlier. Our study of the 2016 presidential campaign found that Trump was the most heavily covered candidate in the national press during every month – and nearly every week – of the 2016 presidential campaign.11Thomas E. Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race: Trump’s Rise, Sanders’ Emergence, Clinton’s Struggle,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, June 13, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/pre-primary-news-coverage-2016-trump-clinton-sanders/;

Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries: Horse Race Reporting Has Consequences,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, July 11, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-presidential-primaries/;

Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions: Negative News, Lacking Context,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, September 21, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-national-conventions/;

Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, December 7, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-general-election/

The media’s obsession with Trump is no mystery. No politician of recent times has so steadily supplied the controversy and novelty that journalists seek in their news stories and that audiences relish. Trump quipped that, within seconds of touching the send button on his Twitter feed, news outlets interrupted what they were doing to announce that there was “breaking news.”

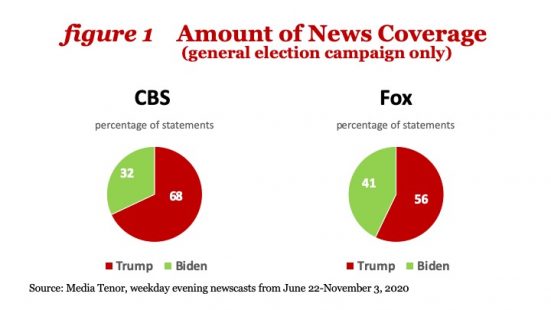

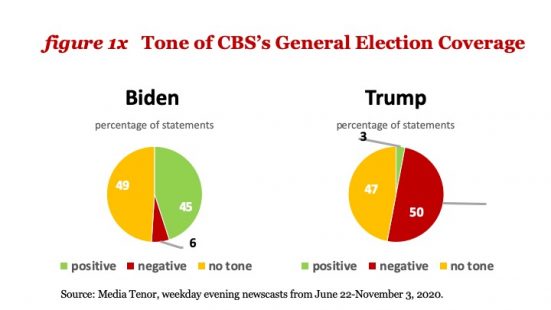

During the 2020 general election (defined as the period from the end of the primary election season to Election Day), Trump’s coverage on Fox outpaced Joe Biden’s by three-to-two (see figure 1). On CBS, the ratio was two-to-one. And those were Biden’s best numbers. Biden was nearly invisible in the news for long periods during the campaign’s earlier stages. Over the course of the full 2020 campaign, Trump received four times as much coverage as Biden on CBS and three times as much on Fox.

CBS and Fox’s Trump focus was nearly the only thing that the two networks shared in 2020. Their coverage is the tale of two elections. The “reality” of the 2020 election as seen on CBS was a stark contrast from how it was presented on Fox. Although it is often said that the United States today has a mainstream news system and a conservative news system, these labels don’t fully capture how CBS and Fox covered the 2020 campaign, as this report will show.

Methodology

The data for our study were provided by Media Tenor, a firm that specializes in collecting and coding news content. Media Tenor’s coding of news stories is conducted by trained full-time employees who visually evaluate the content. Coding of individual actors (e.g., presidential candidates) is done on a comprehensive basis, capturing all reports of more than five lines (print) or five seconds (TV) of coverage for a given actor. For each report, coders identify relevant actors and themes (topics) and evaluate the tone (positive, negative, or having no clear tone). Coding quality is maintained through comprehensive spot checks and inter-coder cross checks to maintain a minimum 85 percent inter-coder reliability rate, which is the standard for evaluating such estimates.

Tone is assessed from the perspective of the candidate. The question is whether that candidate would welcome a news report (positive) or prefer that it not have been reported (negative). Whether a claim is true doesn’t affect tone. In this study, bad news for a candidate is bad news, whether the claim is true, false, or speculative.

Tone is assessed from the perspective of the candidate. The question is whether that candidate would welcome a news report (positive) or prefer that it not have been reported (negative).

This report is confined to the election coverage on CBS Evening News (Monday through Saturday) and Fox’s Special Report (Monday through Friday) – which are the two networks’ major nightly newscasts. Their newscasts differ in length. At 60 minutes in length, Fox’s newscast is twice the length of CBS’s. (The two networks’ talk shows are not included in the analysis.)

Fox News is widely seen as the leading conservative news outlet, which justifies its use as a stand-in for such outlets. Mainstream media, of which CBS is one, don’t have a comparable outlet. Is CBS representative enough of the others for it to be a benchmark? Available evidence suggests that it is. In 2016, we conducted an exhaustive study of presidential election coverage, bridging an 18-month period that ended on Election Day. CBS was part of that study, as were the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USA Today, ABC, CNN, and NBC. CBS’s coverage was like that of other mainstream outlets. Fox, which was also part of that study, was an outlier. Its coverage in 2016 was decidedly more favorable to Trump and less favorable to Clinton than that of the mainstream outlets in the study.2Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race”; Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries”; Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions”; Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” Limited data from 2020 also indicate that CBS is an appropriate stand-in for mainstream media. The 2020 data are from news coverage of the two Trump-Biden presidential debates and include thirteen news outlets, eleven of which were in the mainstream category and two (Fox and Washington Times) in the partisan category. The tone (positive or negative) of CBS’s coverage of Trump and Biden was near the average for the mainstream outlets in the study.3Media Tenor data, first and second presidential general election debates in 2020.

The Good, the Bad, and the Unusual

Judging from past studies, the presidential nominees’ coverage in 2020 should have been negative in tone. Except for Barack Obama in 2008, no presidential nominee since 1984 had received news coverage that was substantially more positive than negative.4Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” Trump and Hillary Clinton in 2016 fared more poorly than most nominees but didn’t top the list. The most negative coverage occurred in the 2000 campaign when reporters questioned whether Al Gore was trustworthy enough and George W. Bush was smart enough to be president.5 “The Last Lap,” Pew Research Center, October 30, 2000. The Pew study found that Gore’s coverage was negative by a balance of 56-13 percent while Bush’s coverage was 49-24 percent negative over positive. When weighted by the amount of campaign coverage devoted to each candidate (29 percent for Gore and 24 percent), the combined average for the two candidates was 75 percent negative to 25 percent positive.

The old journalistic adage that “bad news is good news” has defined recent election reporting. “With malice toward all” is how one study portrayed it.6Patricia Moy and Michael Pfau, With Malice Toward All? (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000). In the six presidential campaigns leading up to the 2020 election, negative coverage of the presidential nominees was 19 percentage points higher than the average for the preceding six elections.7Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” Journalist Joe Klein said, “The biggest change I have seen in our business over the last 40 years has been that journalism has slid from skepticism, which should be our natural state, . . . toward cynicism. It’s gotten to the point where the toughest story for a . . . reporter to write about a politician is a positive story.”8Joe Klein, quoted in Peter Hamby, “Did Twitter Kill the Boys on the Bus?” Shorenstein Center on the Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA., September 2013, p. 93. https://shorensteincenter.org/d80-hamby/

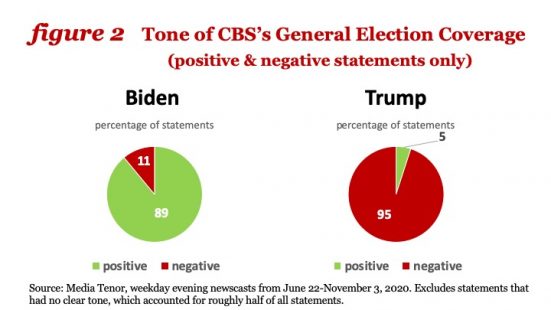

News coverage of the 2020 general election didn’t fully fit the expected pattern. Biden’s coverage on CBS was the most positive ever recorded for a television-age presidential nominee (see figure 2).9Based on a review of past content analysis studies including the one that I conducted (Out of Order, 1993) that included the period from 1960-1992. For later elections, the studies of the Center for Media & Public Affairs, the Pew Research Center, and Media Tenor are the basis for the claim. Of the CBS reports on Biden with a clear tone, 89 percent were positive and only 11 percent were negative. CBS’s coverage of Trump was the reverse. Negative reports outpaced positive ones by 95 percent to 5 percent, easily the most negative coverage a recent nominee has received.10Ibid.

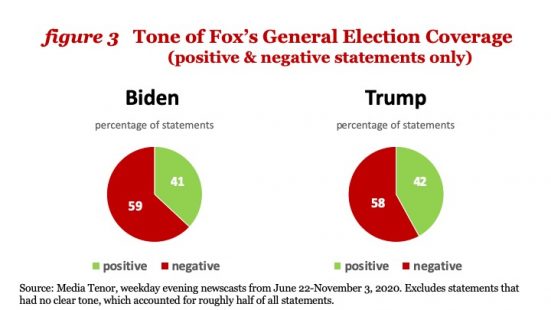

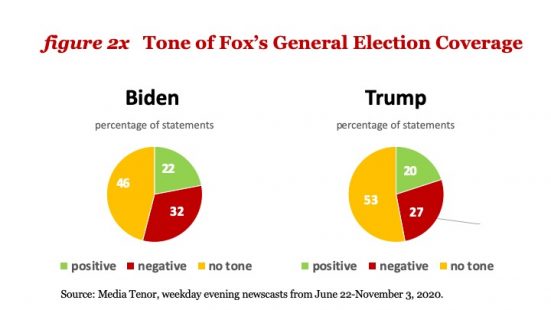

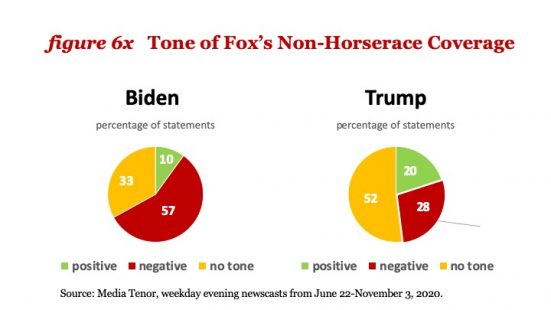

On the other hand, Fox’s coverage was closer to the norm for coverage of recent presidential nominees (see figure 3). In fact, judging from the total general election coverage, Fox appeared to have been even-handed in its reporting. Biden’s reports divided 59 percent negative to 41 percent positive, whereas Trump’s reports split 58 percent negative to 42 percent.

Fox’s profile is deceiving, however. As will be seen, Fox’s reporting of the 2020 general election aligned with expectations for a conservative news outlet. CBS is a different case. Its coverage was a clear departure from that expected of a mainstream news outlet, fitting instead the pattern expected of a partisan outlet.

The Horserace

The “horserace” has been part of election reporting for as long as campaigns have been around. Reports on winning and losing, strategy and tactics, rallies and hoopla are campaign perennials. The plot-like nature of the horserace makes it a natural target of reporters. Whereas policy issues lack the day-to-day novelty that journalists seek, the game is always moving as candidates adjust to the dynamics of the race and their position in it. The game is a reliable source of fresh stories.11Thomas E. Patterson, Out of Order (New York: Knopf, 1993). Nevertheless, the horserace assumed a larger role in the news after the 1960s as election polls multiplied in number. Well over a hundred polls are now conducted during the general election alone, many of which are commissioned by news outlets, and they invariably work their way into and shape the coverage.12Thomas E. Patterson, “Of Polls, Mountains: U.S. Journalists and Their Use of Election Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 69 (2005): 716–724.

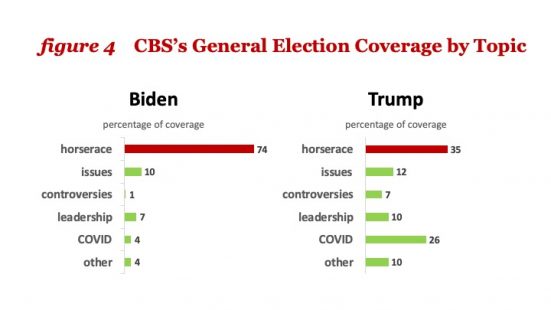

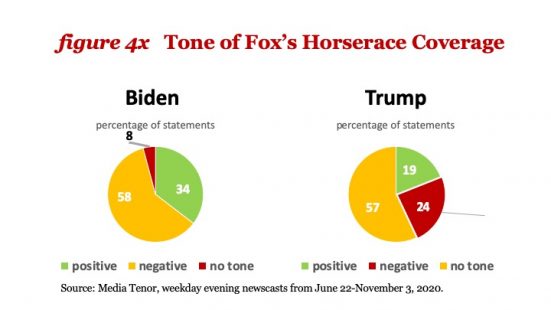

CBS’s reporting on Biden was dominated by horserace stories. They accounted for three of every four reports on Biden. Trump’s coverage on CBS was more diverse, but the horserace was the main topic, accounting for slightly more than a third of news reports.

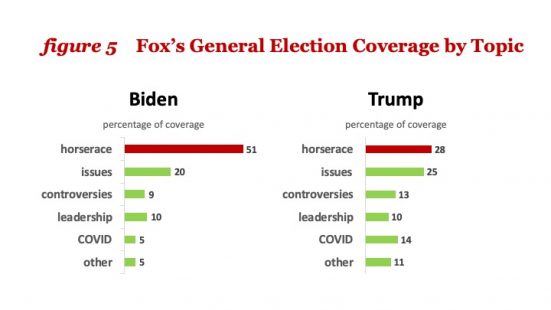

During the 2020 campaign, horserace reports easily outnumbered reports on other topics, including the candidates’ policy positions and their leadership ability. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of CBS’s coverage. Its reporting on Biden was dominated by horserace stories. They accounted for three of every four reports on Biden. Trump’s coverage on CBS was more diverse, but the horserace was the main topic, accounting for slightly more than a third of news reports. Fox’s coverage was less consumed by the horserace (see figure 5). Nonetheless, the horserace was the leading topic in Fox’s coverage. It accounted for half of Biden’s reports and more than a fourth of Trump’s.

When covering the horserace, journalists tend to build their reports around the candidates’ positions in the race, a perspective that affects the tone of these reports. They tend to be a source of positive news for the candidate who’s ahead in the race, except when that candidate is slipping in the polls. Speculation about the reasons for the decline then drive the story, and there’s nothing positive about that narrative.13Ibid.

[Horserace stories] tend to be a source of positive news for the candidate who’s ahead in the race, except when that candidate is slipping in the polls…For the candidate who’s behind in the polls, horserace reports are typically negative in tone.

For the candidate who’s behind in the polls, horserace reports are typically negative in tone. That’s particularly true when the candidate is trailing by a substantial margin and shows no sign of closing the gap. The narrative invariably includes criticism of the candidate’s strategy, positioning, and personal skill. The narrative shifts, however, if the candidate starts to narrow the lead. The story then becomes that of a candidate who’s gaining ground. It’s a story of growing momentum, rising poll numbers, and the smell of victory.14Ibid.

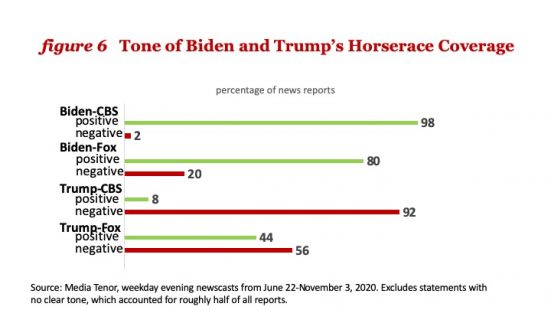

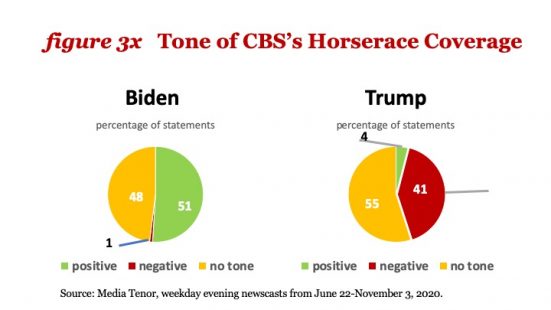

These tendencies played out in CBS and Fox’s horserace coverage. From the time of the last major primaries through Election Day, Biden had the lead in nearly every poll, usually by a comfortable margin. It led to positive horserace coverage, as figure 6 shows.

On CBS, 98 percent of Biden’s horserace reports were positive in tone. Only one in every fifty was negative in tone. Biden’s horserace coverage on Fox was less one-sided but nonetheless highly favorable. Positive horserace reports for Biden outnumbered negative ones by four-to-one.

Trump was in the unenviable position of a likely loser and it showed in his horserace coverage. On CBS, Trump’s horserace reports with a clear tone were 92 percent negative and a mere 8 percent positive. Fox had a more optimistic take on Trump’s chances, although negative horserace reports outpaced positive ones by a 56-44 percent margin. Some of Fox’s favorable coverage was in the context of 2016 polls that wrongly predicted a Trump loss, raising the possibility that he would once again outperform the polls.

Fox’s horserace coverage of Biden provides a clue as to why the tone of his overall coverage on Fox was a near match for that of Trump. Reporters are constrained in interpreting the horserace. They can downplay poll numbers or find occasional reason to question them, but it takes a whole lot of explaining to regularly portray the leading candidate as the likely loser. Biden had the lead, and his horserace coverage on Fox was far more positive than was Trump’s. There was a 36-percentage-point spread in Biden’s favor.

Other aspects of the campaign give journalists more leeway in their claims, and it’s here that journalists’ biases, whether partisan or journalistic, come more clearly into play. It is to these aspects of the 2020 campaign that we now turn.

Biden and Trump’s Fitness for Office

Journalist Walter Lippmann noted a century ago that, unless an object of coverage can be precisely “measured,” journalists’ opinions will affect choices they make.15Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (New York: Free Press, 1965). Originally published in 1922. What are the leadership traits required of a president? There is no definitive list for reporters to consult, nor is there a precise standard for judging whether a candidate possesses a particular trait. What constitutes “trustworthiness”? Consistency of opinion? Fulfillment of promises? Loyalty? Likemindedness? On all such matters, journalists have leeway in their judgments.

Fox’s Biden Coverage

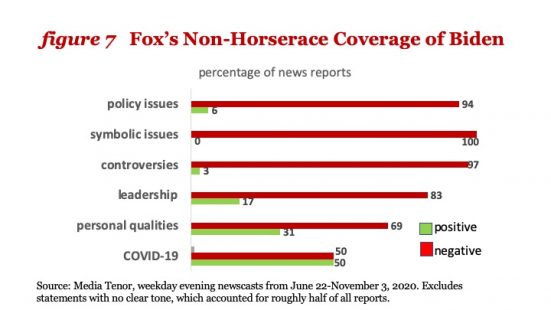

Fox’s partisanship surfaced in its coverage of the more subjective aspects of Biden’s candidacy (see figure 7). In fact, Fox had almost nothing good to say about Biden outside of the horserace.

Biden’s policy stands accounted for 15 percent of his Fox coverage and were uniformly criticized. His economic, tax, and energy positions, for example, were played up, and put down. Overall, 94 percent of reports on his policy positions that had tone were negative in tone.

Biden’s policy stands accounted for 15 percent of his Fox coverage and were uniformly criticized.

Biden’s pronouncements on symbolic issues – such as racial justice, border security, and world peace – accounted for only 5 percent of his Fox coverage but got uniformly negative treatment. All such reports that had a clear tone were unfavorable in tone.

“Controversies” that ensnare a candidate have long been part of election coverage, and no modern-day presidential nominee has avoided them. Biden contended, for example, with allegations of profiteering directly and through his son Hunter on deals in China and the Ukraine. Such allegations accounted for 9 percent of his Fox reports, and they were one-sidedly unfavorable – 97 percent negative to 3 percent positive.

Aside from COVID-related reports, which accounted for 5 percent of Biden’s coverage and broke 50-50 positive to negative, Biden’s personal qualities, such as his demeanor and personality, were the basis for his most favorable coverage on Fox. But the coverage was favorable only in relationship to other aspects of his coverage. Such reports divided 69 percent negative to 31 percent positive. Biden’s leadership ability was also unfavorably reported on Fox. Accounting for 3 percent of his Fox coverage, such reports divided 83 percent negative to 17 percent positive.

Fox’s Trump Coverage

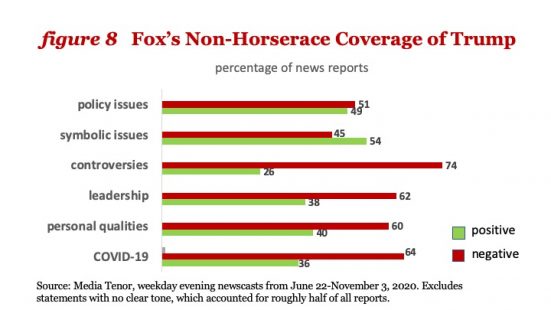

Fox’s coverage of Trump was negative but much less so than Biden’s (see Figure 8). Like most journalists, those at Fox tend to see “bad news as good news,” and it directs their attention to the candidates’ failings and problems. Nevertheless, that tendency on Fox was conditioned by partisanship.

There was only a single category – COVID-19 – in which Fox gave Trump less favorable coverage than it did Biden. Whereas COVID-19 reports involving Biden divided 50-50, Trump’s divided 69-31 percent negative to positive.

Trump’s most favorable coverage on Fox came through its issue reporting. Trump’s policy stands, which accounted for 13 percent of his Fox reports, divided nearly 50-50, while his statements on symbolic issues (12 percent of his total coverage) edged into positive territory by a 54-46 percent margin. Trump’s coverage on each of these topics was more than 40-percentage points more positive than was Biden’s.

When it came to reports touching on Trump as a person, Fox’s reporting on balance was unfavorable – roughly three-to-two negative for both his personal qualities and his leadership. But here again, Trump’s coverage on Fox was substantially more positive than was Biden’s.

Controversies accounted for Trump’s worst coverage on Fox.

Controversies accounted for Trump’s worst coverage on Fox. Trump’s tax filings, racial remarks, and other flare-ups constituted 13 percent of his Fox reports and divided 74-26 percent negative over positive. Nevertheless, Biden fared worse in that area – his coverage on Fox was 97 percent negative to 3 percent positive.

Fox’s partisan slant was also evident in what it highlighted and downplayed. On both CBS and Fox, news reports about Trump and COVID-19 were negative on balance. However, whereas COVID-19 accounted for 26 percent of CBS’s Trump coverage, it accounted for only 14 percent of Fox’s Trump coverage.

CBS’s Trump Coverage

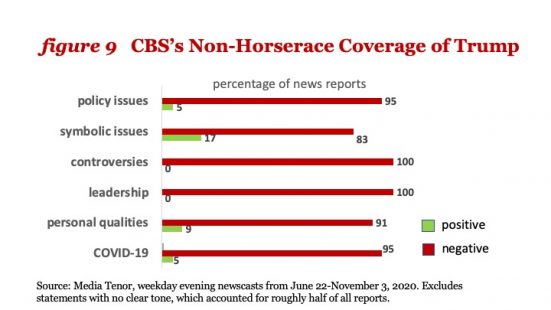

Trump’s coverage on CBS can be summarized in a single sentence: it was the most negative coverage ever recorded for a television-age presidential nominee.16Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” When all the non-horserace categories of Trump’s CBS coverage are combined, the coverage was 95 percent negative to 5 percent positive.

Trump’s coverage on CBS can be summarized in a single sentence: it was the most negative coverage ever recorded for a television-age presidential nominee.

No aspect of Trump’s CBS coverage was even marginally favorable (see figure 9). When it came to reports on his leadership traits, which accounted for 4 percent of his CBS coverage, none were positive. Reports on his personal qualities were nearly at the same level – negative reports outpaced positive ones by ten-to-one. As for the controversies surrounding Trump, CBS reported nothing of a positive nature. All such reports were negative.

Whereas Fox had found positive things to say about Trump’s policy stands and symbolic issue statements, CBS found few. Reports on his policy positions were 95 percent negative; those on symbolic issues were 83 percent negative.

COVID-19 accounted for a significant share – 26 percent – of CBS’s coverage of Trump’s candidacy. It, too, contributed to his overwhelmingly unfavorable coverage on CBS. Negative reports outnumbered positive ones by nineteen-to-one.

CBS’s Biden Coverage

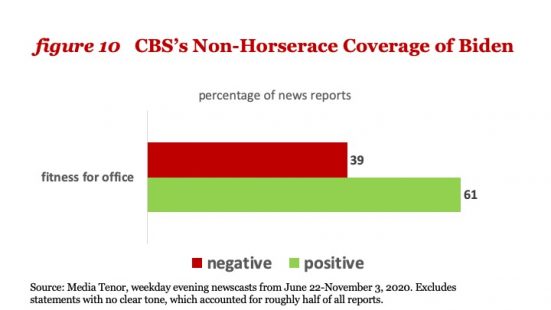

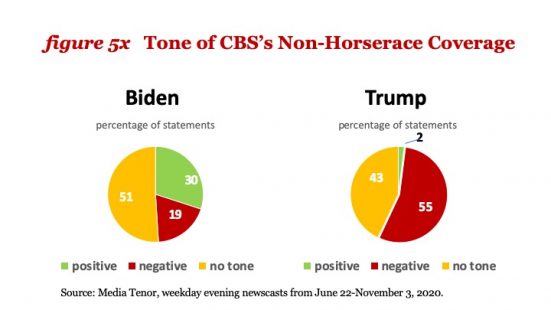

CBS’s coverage of Biden was a sharp contrast with its Trump coverage. Focused heavily on the horserace, it included relatively few reports that spoke to his fitness for office, so few in fact that the topics have been combined into a single category (“fitness for office”) in order to obtain a reliable estimate (see Figure 10).

CBS’s coverage of Biden…focused heavily on the horserace [and] included relatively few reports that spoke to his fitness for office

Biden’s non-horserace reports on CBS were strongly favorable, given that presidential nominees typically receive more negative than positive coverage. On reports that spoke to Biden’s policy positions, symbolic issue statements, controversites, personal qualities, leadership, and COVID, the coverage divided three-to-two positive over negative. By comparison, when Trump’s reports on these same dimensions are combined, the coverage divided nineteen-to-one negative over positive. The difference is far and away the widest divide between the Republican and Democrat nominees ever recorded in a content analysis of presidential election coverage.17Ibid.

The General Pattern and a Conclusion

As noted earlier in this report, previous studies of election news coverage would have predicted, first, that the horserace would be the dominant theme of the 2020 coverage; second, that a mainstream news outlet would play up the negative aspects of both nominees; and third, that a partisan outlet would favor one nominee over the other.

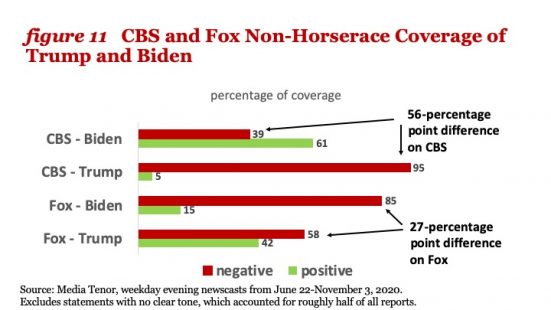

Fox’s coverage aligned with expectations for a partisan outlet. Its coverage of Trump’s fitness for office, although slanted toward the negative, was markedly more favorable than was its coverage of Biden’s fitness for office. When all “fitness” categories are combined (see Figure 11), Trump’s reports on Fox were 58-42 percent negative to positive whereas Biden’s reports were 85-15 percent negative to positive – a 27-percentage-point spread.

CBS’s coverage aligned with what would be expected of a partisan outlet rather than a mainstream news outlet. In fact, the 56 percentage point spread between Trump and Biden on all “fitness” categories combined was twice that of Fox’s spread. CBS aligned itself more fully with Biden’s candidacy than Fox did with Trump’s candidacy. However, its slim coverage of Biden’s fitness for office and its robust coverage of Trump’s fitness for office suggests that CBS’s coverage was less a case of being “all in” on Biden’s candidacy than of being “all out” in its opposition to Trump.

Its slim coverage of Biden’s fitness for office and its robust coverage of Trump’s fitness for office suggests that CBS’s coverage was less a case of being “all in” on Biden’s candidacy than of being “all out” in its opposition to Trump.

The horserace was, as predicted, the major category of coverage on both CBS and Fox, but CBS gave it far more play than Fox. In this respect, CBS’s reporting aligned with how mainstream outlets have covered past campaigns. “No time for issues” is how an earlier study described journalists’ fascination with the horserace.18Thomas E. Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980). That description didn’t fit as tightly in Fox’s case. A horserace story is often the lead election story in a newscast, and the greater length of Fox’s newscasts (60 minutes versus CBS’s 30 minutes) might account for why other types of stories were a larger part of its lineup. A second possibility is that non-horserace stories are a higher priority for a partisan outlet. Policy and leadership differences address partisan differences more directly than do horserace stories. It’s also possible that Fox had less interest in highlighting the horserace in 2020 because its preferred candidate was losing.

Mainstream Media and the Rise and Fall of Donald Trump

In 2016, the mainstream media contributed to Donald Trump’s election to the presidency. Without their help, Trump’s presidency might have been stillborn.

The boost started the day that Trump announced his candidacy. He lacked the attributes that in earlier elections would have marked him as a plausible contender and thereby a candidate deserving of close attention. He was far down in the polls and had raised almost no money. He had no political base and no claim to being prepared to handle the demands of the presidency. What he had going for him was his TV celebrity status and his skill at provoking controversy. Ratings shot up when he appeared on the air. CBS news president Les Moonves remarked, “Donald Trump may not be good for America but he’s damn good for CBS.”19Alex Weprin, “CBS CEO Les Moonves clarifies Donald Trump ‘good for CBS’ comment,” Politico, October 19, 2016. https://www.politico.com/blogs/on-media/2016/10/cbs-ceo-les-moonves-clarifies-donald-trump-good-for-cbs-comment-229996 “If we break away from the Trump story,” CNN president Jeff Zucker said, “the audience goes away.”20John Bowden, “CNN boss: If we break away from Trump coverage ‘the audience goes away,’” The Hill, November 1, 2018. https://thehill.com/homenews/media/414390-cnn-boss-if-we-break-from-trump-coverage-the-audience-goes-away

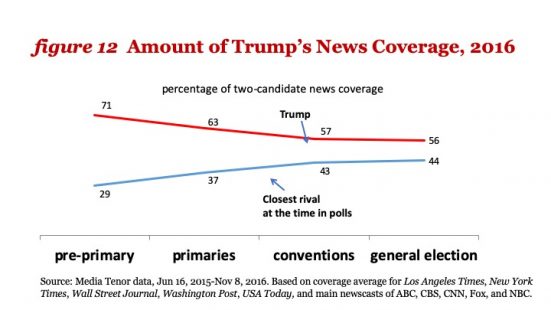

Trump’s domination of the coverage continued throughout the 2016 campaign (see figure 12). There was not a single period when Trump’s chief rival at any point in the campaign got more news coverage than he did.

In the early phase of a presidential nominating race, nothing is more valuable than being the center of media attention. Media attention provides a boost in the polls, while reducing the need to raise televised ad money. A study calculated Trump’s early news coverage as having a value exceeding $100 million.21Thomas E. Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race.” “The Great Mentioner” is how the New York Times’ Russell Baker in the 1960s described the press’s ability to transform a presidential hopeful into a bona fide contender.22Richard Cohen, “One View,” Washington Post, November 17, 1981. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1981/11/17/one-view/546e14e8-5942-4cf7-9b23-3560785eb988/

When Trump first entered the 2016 race, his news coverage was positive on balance, a reflection of the media’s focus on the horserace and his rising poll numbers.

When Trump first entered the 2016 race, his news coverage was positive on balance, a reflection of the media’s focus on the horserace and his rising poll numbers, followed by his victories in GOP primaries.23Thomas E. Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980). After he had piled up enough delegate votes to get a lock on the nomination, news outlets scrutinized his issue positions and personal background more closely and his coverage turned negative.24Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries.” News outlets by then had also settled on their characertization of Trump. They portrayed him as forceful, but that positive portrayal was rested alongside a negative one – that he was bigoted, insulting, unprepared, and narcissistic.25Ibid.

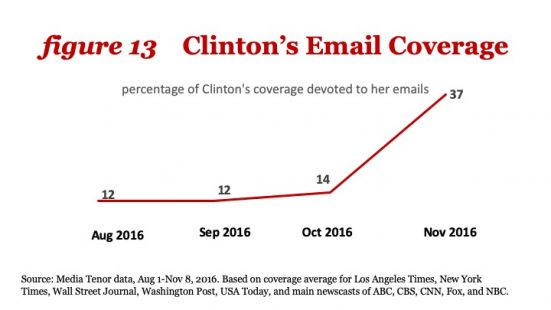

Trump’s domination of the news allowed him to define his opponents. He typecast his Republican primary rivals with labels like “Lying Ted” and “Little Marco,”‘26Ibid. a tactic he then used to undermine Hillary Clinton.27Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” On CNN alone during the 2016 campaign, “Crooked Hillary” and “Lock Her Up” were aired nearly 3,000 times.28Compiled by author from UCLA’s television archive database, February 2017. Trump’s attacks combined with journalists’ focus on Clinton’s emails to drive down her favorability rating and foster the perception that she couldn’t be trusted.29“Poll: Email Investigation Damaged Hillary Clinton’s Image,” CBS News, July 15, 2016. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/poll-email-investigation-damaged-hillary-clintons-image/

Journalists’ obsession with Clinton’s emails was no surprise. Controversies have been a staple of election coverage since at least 1976 when Democratic nominee Jimmy Carter said in a Playboy interview that he had “looked at a lot of women with lust.” Some of these controversies have had a bearing on the type of president a candidate might make, but most, as with Clinton’s emails, have had dubious connection. They make news not because of their inherent value but for their news value. Gaffes, blunders, and indiscretions have the makings of a great story that has the possibility of shaking up a race.30The best analysis of this tendency is still, years later, Maura Clancy and Michael Robinson, “General Election Coverage, Part I,” in The Mass Media in Campaign ’84, ed. Michael Robinson and Austin Ranney (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1985), 29.

In Clinton’s case, the emails likely cost her the election. The breaking point was FBI director James Comey’s relaunch of the email investigation less than two weeks before Election Day. Her lead in the polls from that point to Election Day shrank by 5 percentage points. News coverage fueled the drop. Although her emails had been a top story throughout the general election, they jumped to more than a third of the coverage in mainstream news outlets (see figure 13). More than 90 percent of that coverage was negative in tone. During the 2016 general election, Clinton’s emails received than fifteen times more coverage than did her most heavily covered policy position.31Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.” To this day, reporters have not made the case for why Clinton’s emails were such a huge story.

On national television during his first 100 days in office, Trump was the topic of 41 percent of all news stories—three times the usual amount for a newly inaugurated president.

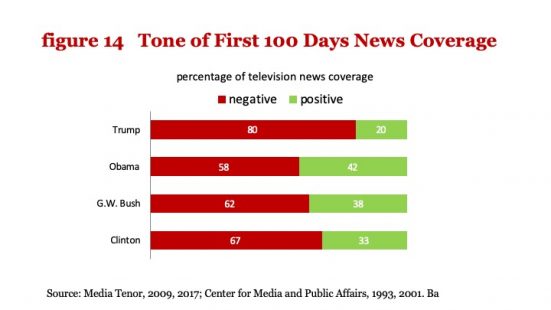

Upon becoming president, Trump became an even larger presence in the news than he had been during the 2016 campaign. On national television during his first 100 days in office, Trump was the topic of 41 percent of all news stories—three times the usual amount for a newly inaugurated president.32Trump’s percentage based on content analysis of Media Tenor from January 20-April 29, 2017 on newscasts of CBS, CNN, Fox, and NBC. Estimate for earlier presidents based on data in Jeffrey E. Cohen, The Presidency in the Era of 24-Hour News (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 33. But it was no honeymoon, even by the standards of recent presidents (see figure 14). His coverage was four-to-one negative, easily topping the two-to-one negative coverage that Clinton received and the three-to-two negative coverage bestowed on Obama and George W. Bush during their first weeks in office. At that, Trump’s coverage during his first 100 days was about as good as it would get. His subsequent coverage logged in at more than 90 percent negative over positive for extended periods.33See, Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Galen Stocking, Katerina Eva Matsa, and Elizabeth Grieco, “Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment,” Pew Research Center, October 2, 2017. https://www.journalism.org/2017/10/02/covering-president-trump-in-a-polarized-media-environment/; “Media Trump Hatred Shows In 92% Negative Coverage Of His Presidency: Study,” Investors Business Daily, October 10, 2018. https://www.investors.com/politics/editorials/media-trump-hatred-coverage/.

Trump asked for trouble the day that he turned on the press with his claims of “fake news” and “lying media.” Other recent presidents had largely refrained from striking back at news outlets for what they believed was unfair criticism. Not Trump. He began his attacks on the media the minute that his 2016 campaign coverage turned sour. Trump tweeted that the “election is being rigged by the media, in a coordinated effort with the Clinton campaign.”34Trump tweet, October 16, 2016.

Journalists have traditionally refrained from attacking political leaders on their policies but have not hesitated to call them out for damaging the norms on which democracy depends.

Trump crossed another line with the press by trampling on democratic norms. Journalists have traditionally refrained from attacking political leaders on their policies but have not hesitated to call them out for damaging the norms on which democracy depends. No president in recent memory, perhaps ever, has so wantonly diminished the dignity of his office – attacking the justice system, belittling Congress, snubbing traditional allies, pardoning cronies, claiming elections are rigged, and on and on. And for certain, no president has lied with as much abandon as Trump. The Washington Post’s ongoing tally of his false and misleading statements exceeded the 20,000 mark.35Glenn Kessler, Salvador Rizzo, and Meg Kelly, “President Trump has made more than 20,000 false or misleading claims,” Washington Post, July 13, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/07/13/president-trump-has-made-more-than-20000-false-or-misleading-claims/ Healthcare alone was occasion for thousands of inaccurate and deceptive claims.36William Hatcher, “President Trump and health care: a content analysis of misleading statements,” Journal of Public Health 42 (2020): e482–e486. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz176.

It’s difficult to separate the bad press that Trump deserved from the bad press resulting from journalists’ dislike of his person and his policies. In a 2019 ranking by scholars, Trump rated as the third-worst president in the nation’s history, placing ahead of only James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson.37William Cummings, “Survey of scholars places Trump as third worst president of all time,” USA Today, February 13, 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2019/02/13/siena-presidential-ranking-survey/2857075002/ A historically bad presidency warrants historically bad coverage.

Yet, the coverage of his policies indicates that the mainstream press was reacting to more than a callous president. Traditional journalism calls for reporters to avoid taking sides in disputes between the parties.38See, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism, revised edition (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007). That norm went out the window with Trump. To be sure, there were instances, many in fact, where reporters were responding primarily to the way that Trump was pursuing his goals. No president, Republican or Democratic, would have escaped withering criticism from the wholesale separation of children from their parents at the border.

On nearly every policy issue – everything from climate change to border security to welfare assistance – the mainstream press pushed back against what Trump was proposing.

Nevertheless, Trump’s populist ideology was at odds with the dominant ideology of the mainstream media.39Bart Bonikowski, “Trump’s Populism,” in Kurt Weyland and Raúl Madrid, eds., When Democracy Trumps Populism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 110-131. The nationalism and anti-elitism underlying Trump’s actions, and that fueled his popular support, was not their view of what America is, or should be, and it affected their coverage.40“Media Trump Hatred Shows.” Establishment critics of Trump’s agenda, many of whom had served in the George W. Bush or Obama administration, featured prominently in the news throughout his presidency.41See, for example, David Ignatius, “Former CIA director John Brennan takes on Trump, and doesn’t hold back,” Washington Post, October 9, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/former-cia-director-john-brennan-takes-on-trump-and-doesnt-hold-back/2020/10/08/6754f6f4-0962-11eb-859b-f9c27abe638d_story.html On nearly every policy issue – everything from climate change to border security to welfare assistance – the mainstream press pushed back against what Trump was proposing.42“Media Trump Hatred Shows.” The 2017 Tax Relief and Jobs Act was attacked on its content43See, for example, Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Tax Cuts Benefit the Ultra Rich, Not the Merely Rich,” New York Times, December 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/business/dealbook/tax-bill-wealthy.html. – an example of “taking sides.” Other examples are the media’s reporting on the stripping of the individual mandate from the 2010 Affordable Care Act,44See, for example, Robert Pear, “Without the Individual Mandate, Health Care’s Future May Be in Doubt,” New York Times, December 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/us/politics/tax-cut-obamacare-individual-mandate-repeal.html. their coverage of Trump’s trade war with China,45See, for example, Heather Long, “Was Trump’s China trade war worth it?” Washington Post, January 15, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/01/15/was-trumps-china-trade-war-worth-it/. and their reporting on the status of Dreamers – the undocumented immigrants brought to America as children.46See, for example, Francesco Rodella and María Peña, “’Very alarmed’: Dreamers slam Trump’s new limits on DACA program,” NBC News, July 29, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/very-alarmed-dreamers-slam-trump-s-new-limits-daca-program-n1235184.

Many in the mainstream press would reject this interpretation of their reporting on grounds that Trump’s policies harmed America, both here and abroad, and that it was their responsibility to expose the harms. That’s a defensible position but it departs from the press’s traditional role as a neutral player in partisan politics. Trump, as the stubborn loyalty of his base indicates, was the carrier of beliefs held by a great many Americans and that largely define today’s Republican Party.47Thomas E. Patterson, Is the Republican Party Destroying Itself? (Seattle, WA: KDP Publishing, 2020). Trump’s policy agenda received solid support from congressional Republicans48“Tracking Congress In The Age Of Trump,” FiveThirtyEight, December 11, 2020. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/congress-trump-score/. and states controlled by Republican officeholders.49See, for example, Zach Montellaro and Josh Gerstein, “GOP-led states back Trump’s legal drive to challenge election,” Politico, November 9, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/11/09/gop-states-back-trump-election-challenge-435437 Right-wing populism defined Republican politics before Trump came on the scene50E.J. Dionne, Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism–From Goldwater to the Tea Party and Beyond (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016). – in fact, it underpinned his nomination in 2016 as the Republican standard bearer51Exit polls of 2016 Republican presidential primaries found that a majority of Republican voters were angry at the “Republican Establishment” and that those who were voted overwhelmingly for Trump. – and will do so when he leaves office.52Patterson, Is the Republican Party Destroying Itself? The mainstream press can stand against that brand of politics but, in doing so, will be standing against what is now the Republican brand.

For decades, Republicans have complained that the national press has a strong liberal bias. Some studies found no evidence for it, whereas others concluded that there was a slight leftward tilt to the news. No reliable study found a pattern that supported what Republicans were claiming.53David D’Alessio and Mike Allen, “Media Bias in Presidential Elections: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Communication 50 (2000):133–56. That changed with Trump.

Now that he’s about to leave office, will the mainstream press find a way to walk back its advocacy role? Or, as happened after the Watergate scandal, will a new journalism model take hold, one that retains features of the older model but includes a greater degree of advocacy?

Economic considerations could push some national news outlets in the direction of advocacy journalism. America’s conservative media system – rooted in Fox, right-wing talk shows, and alt-right web outlets – now has an audience that exceeds 50 million Americans, the great majority of whom are Repubicans.54Nicole Hemmer, Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018). As Republicans have drifted away, mainstream outlets have been left with an audience that’s disproportionately Democratic. Responding to that audience will be tempting. Studies indicate that news consumers increasingly are attracted to outlets that play to their partisan interests.55Michael S. Pollard and Jennifer Kavanagh, Profiles of News Consumption: Platform Choices, Perceptions of Reliability, and Partisanship (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2019).

The mainstream media’s tendency to overplay what’s wrong with government and political leaders, while underplaying what’s they’re doing well, reinforces Republicans’ anti-government message.

Nevertheless, tradition is a powerful force, and mainstream outlets could revert to a version of their traditional reporting model. If they do so, they should be mindful of how some of their traditions contributed to the rise of Trump and unduly bolster the Republican side. The mainstream media’s tendency to overplay what’s wrong with government and political leaders, while underplaying what’s they’re doing well, reinforces Republicans’ anti-government message.56Thomas E. Patterson, How America Lost Its Mind (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2019). And the highlighting of controversies, such as the feeding frenzy surrounding Clinton’s emails, tilts the playing field in Republicans’ favor. When a Republican candidate gets tangled in controversy, right-wing media dampen the effect by seeking to deflate it. When a Democratic candidate gets caught up in one, right-wing media heighten the effect by doing their utmost to amplify it. Would Trump have been derailed in 2016 if he had been dogged throughout his campaign by allegations of the misuse of emails? It’s unlikely given that the Access Hollywood tapes failed to do it. As the mainstream media were portraying the tapes as an assault on women and giving them lots of ink, conservative media were playing them down and dismissing them as “locker room talk.”57Lindsay Bever, “Here comes the rape police: Rush Limbaugh reacts to Trumps “sex-talk scandal,’” Washington Post, October 13, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/10/13/here-come-the-rape-police-rush-limbaugh-reacts-to-trumps-sex-talk-scandal/

America is at a crossroads. Our major parties are offering starkly different visions of the nation’s future. The stakes have rarely been higher, and the voters will ultimately determine which vision will win out. The mainstream press should focus on clarifying rather than confounding that choice.

Appendix

Figures with “No tone” Reports Included

Endnotes

- Thomas E. Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race: Trump’s Rise, Sanders’ Emergence, Clinton’s Struggle,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, June 13, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/pre-primary-news-coverage-2016-trump-clinton-sanders/; Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries: Horse Race Reporting Has Consequences,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, July 11, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-presidential-primaries/; Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions: Negative News, Lacking Context,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, September 21, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-national-conventions/; Thomas E. Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election: How the Press Failed the Voters,” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, December 7, 2016. https://shorensteincenter.org/news-coverage-2016-general-election/.

- Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race”: Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries”; Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 National Conventions”; Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- Media Tenor data, first and second presidential general election debates in 2020.

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- “The Last Lap,” Pew Research Center, October 30, 2000. The Pew study found that Gore’s coverage was negative by a balance of 56-13 percent while Bush’s coverage was 49-24 percent negative over positive. When weighted by the amount of campaign coverage devoted to each candidate (29 percent for Gore and 24 percent), the combined average for the two candidates was 75 percent negative to 25 percent positive.

- Patricia Moy and Michael Pfau, With Malice Toward All? (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000).

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- Joe Klein, quoted in Peter Hamby, “Did Twitter Kill the Boys on the Bus?” Shorenstein Center on the Media, Politics and Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA., September 2013, p. 93. https://shorensteincenter.org/d80-hamby/

- Based on a review of past content analysis studies including the one that I conducted (Out of Order, 1993) that included the period from 1960-1992. For later elections, the studies of the Center for Media & Public Affairs, the Pew Research Center, and Media Tenor are the basis for the claim.

- Ibid.

- Thomas E. Patterson, Out of Order (New York: Knopf, 1993).

- Thomas E. Patterson, “Of Polls, Mountains: U.S. Journalists and Their Use of Election Surveys,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 69 (2005): 716–724.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (New York: Free Press, 1965). Originally published in 1922.

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- Ibid.

- Thomas E. Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980).

- Alex Weprin, “CBS CEO Les Moonves clarifies Donald Trump ‘good for CBS’ comment,” Politico, October 19, 2016. https://www.politico.com/blogs/on-media/2016/10/cbs-ceo-les-moonves-clarifies-donald-trump-good-for-cbs-comment-229996

- John Bowden, “CNN boss: If we break away from Trump coverage ‘the audience goes away,’” The Hill, November 1, 2018. https://thehill.com/homenews/media/414390-cnn-boss-if-we-break-from-trump-coverage-the-audience-goes-away

- Thomas E. Patterson, “Pre-Primary News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Race.”

- Richard Cohen, “One View,” Washington Post, November 17, 1981. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1981/11/17/one-view/546e14e8-5942-4cf7-9b23-3560785eb988/

- Thomas E. Patterson, The Mass Media Election (New York: Praeger, 1980).

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 Presidential Primaries.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- Compiled by author from UCLA’s television archive database, February 2017.

- “Poll: Email Investigation Damaged Hillary Clinton’s Image,” CBS News, July 15, 2016. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/poll-email-investigation-damaged-hillary-clintons-image/

- The best analysis of this tendency is still, years later, Maura Clancy and Michael Robinson, “General Election Coverage, Part I,” in The Mass Media in Campaign ’84, ed. Michael Robinson and Austin Ranney (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1985), 29.

- Patterson, “News Coverage of the 2016 General Election.”

- Trump’s percentage based on content analysis of Media Tenor from January 20-April 29, 2017 on newscasts of CBS, CNN, Fox, and NBC. Estimate for earlier presidents based on data in Jeffrey E. Cohen, The Presidency in the Era of 24-Hour News (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 33.

- See, Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Galen Stocking, Katerina Eva Matsa, and Elizabeth Grieco, “Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment,” Pew Research Center, October 2, 2017. https://www.journalism.org/2017/10/02/covering-president-trump-in-a-polarized-media-environment/; “Media Trump Hatred Shows In 92% Negative Coverage Of His Presidency: Study,” Investors Business Daily, October 10, 2018. https://www.investors.com/politics/editorials/media-trump-hatred-coverage/.

- Trump tweet, October 16, 2016.

- Glenn Kessler, Salvador Rizzo, and Meg Kelly, “President Trump has made more than 20,000 false or misleading claims,” Washington Post, July 13, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/07/13/president-trump-has-made-more-than-20000-false-or-misleading-claims/

- William Hatcher, “President Trump and health care: a content analysis of misleading statements,” Journal of Public Health 42 (2020): e482–e486. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz176.

- William Cummings, “Survey of scholars places Trump as third worst president of all time,” USA Today, February 13, 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2019/02/13/siena-presidential-ranking-survey/2857075002/

- See, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism, revised edition (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007).

- Bart Bonikowski, “Trump’s Populism,” in Kurt Weyland and Raúl Madrid, eds., When Democracy Trumps Populism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 110-131.

- “Media Trump Hatred Shows.”

- See, for example, David Ignatius, “Former CIA director John Brennan takes on Trump, and doesn’t hold back,” Washington Post, October 9, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/former-cia-director-john-brennan-takes-on-trump-and-doesnt-hold-back/2020/10/08/6754f6f4-0962-11eb-859b-f9c27abe638d_story.html

- “Media Trump Hatred Shows.”

- See, for example, Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Tax Cuts Benefit the Ultra Rich, Not the Merely Rich,” New York Times, December 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/business/dealbook/tax-bill-wealthy.html.

- See, for example, Robert Pear, “Without the Individual Mandate, Health Care’s Future May Be in Doubt,” New York Times, December 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/us/politics/tax-cut-obamacare-individual-mandate-repeal.html.

- See, for example, Heather Long, “Was Trump’s China trade war worth it?” Washington Post, January 15, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/01/15/was-trumps-china-trade-war-worth-it/.

- See, for example, Francesco Rodella and María Peña, “’Very alarmed’: Dreamers slam Trump’s new limits on DACA program,” NBC News, July 29, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/very-alarmed-dreamers-slam-trump-s-new-limits-daca-program-n1235184.

- Thomas E. Patterson, Is the Republican Party Destroying Itself? (Seattle, WA: KDP Publishing, 2020).

- “Tracking Congress In The Age Of Trump,” FiveThirtyEight, December 11, 2020. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/congress-trump-score/.

- See, for example, Zach Montellaro and Josh Gerstein, “GOP-led states back Trump’s legal drive to challenge election,” Politico, November 9, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/11/09/gop-states-back-trump-election-challenge-435437

- E.J. Dionne, Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism–From Goldwater to the Tea Party and Beyond (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016).

- Exit polls of 2016 Republican presidential primaries found that a majority of Republican voters were angry at the “Republican Establishment” and that those who were voted overwhelmingly for Trump.

- Patterson, Is the Republican Party Destroying Itself?

- David D’Alessio and Mike Allen, “Media Bias in Presidential Elections: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Communication 50 (2000):133–56.

- Nicole Hemmer, Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).

- Michael S. Pollard and Jennifer Kavanagh, Profiles of News Consumption: Platform Choices, Perceptions of Reliability, and Partisanship (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2019).

- Thomas E. Patterson, How America Lost Its Mind (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2019).

- Lindsay Bever, “Here comes the rape police: Rush Limbaugh reacts to Trumps “sex-talk scandal,’” Washington Post, October 13, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/10/13/here-come-the-rape-police-rush-limbaugh-reacts-to-trumps-sex-talk-scandal/