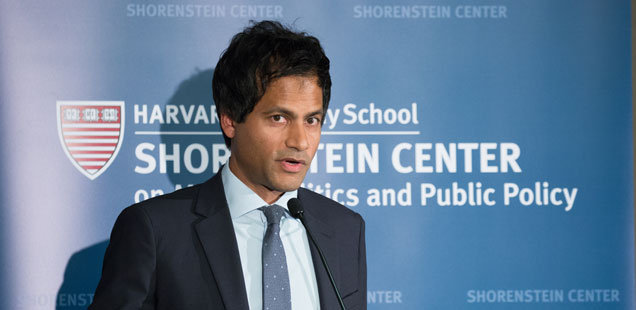

Jameel Jaffer, Executive Director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University and former Deputy Legal Director for the ACLU, delivered the tenth annual Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on October 17, 2017, entitled “Government Secrecy in the Age of Information Overload.” Watch the video and read the transcript below.

Nicco Mele: Welcome to the Salant Lecture. Did anybody watch 60 Minutes Sunday night? Anybody see that? There was this incredible piece of investigative news about the role of lobbyists in rolling back DEA regulations last year, that contributed substantially to the opioid epidemic. It was exceptional and a mind-boggling piece of investigative reporting, and as a result of this investigation by CBS and The Washington Post, Congressman Tom Marino, this morning, withdrew his nomination to be Trump’s drug czar. Why am I telling you this story? Richard Salant was the president of CBS News. And it was under his watch that 60 Minutes started—he didn’t create 60 Minutes, Bill Leonard and Don Hewitt did—but they came to him and asked him to fund it, to start it. And it’s actually almost impossible to imagine, in many ways, CBS News, under Dick Salant’s leadership, created television news. An almost unimaginable opportunity to innovate. And then at the end of his career, he was giving speeches—I was reading some of them last week—in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, where he was really upset about the trends in television news towards docudrama, which we might otherwise call reality television today.

At first, Dick Salant seemed like an unlikely choice to lead CBS News. He was a corporate lawyer. And his job was mostly explaining to journalists at CBS why they couldn’t do things like that. In fact, the leading journalists of CBS were so upset that a lawyer was their new boss, that Walter Cronkite took some of his colleagues, and they went up to see Frank Stanton, the president of CBS, to complain. The only reason you’d put a lawyer in charge is if you wanted to censor something and kill it. Cronkite later wrote, “I couldn’t see any other function that a lawyer would be serving in the newsroom. We were all so depressed.” Well, how wrong they turned out to be. Ten years later, CBS News, in 1971, aired an hour-long special, The Selling of the Pentagon. It is hard to imagine today, but it used to be that broadcast news would spend 60 minutes investigating something, the whole hour. Not 60 Minutes the show, but an hourlong special during primetime, which was an investigative report. This one by CBS, The Selling of the Pentagon, took a year for them to make, and it was about all the ways the Pentagon would try to sell the Vietnam War to the American people, including the revelation that the Pentagon had sent their own film crews to Vietnam, and staged a battle that they later had to admit was totally fabricated for the cameras. In the midst of the Vietnam War, the actions the Pentagon was taking with public relations and managing their brand, media management, were shocking to the American people.

Congress was outraged that CBS would do this kind of journalism. Congressman Harley Staggers, a Democrat of West Virginia, was chair of the investigations subcommittee of the House Commerce Committee, and he launched an investigation into CBS News and The Selling of the Pentagon. Why would he launch an investigation? On what grounds? Electronic media was not protected by the First Amendment, he argued—the only thing the First Amendment protected was printed newspaper. The airwaves, broadcast, belonged to the American people, not to the press, and it was the duty of Congress to police those airwaves. The committee subpoenaed CBS News’ notes and archival footage, and hauled all the senior executives in front of the big lights for Congressional testimony. And if Walter Cronkite had at first been terrified of having a lawyer running the newsroom, he now found Dick Salant an inspired choice. They were under intense pressure from Congress, but Dick Salant and his boss Frank Stanton refused to back down from the story, would not turn over any notes or outtakes, or any of the footage. Frank Stanton gave testimony to Congress where he refused to hand over the subpoenaed material, even though they were putting on this pressure, and saying they were going to hold him in contempt. And in fact, the House Commerce Committee voted to recommend that the House of Representatives hold Stanton in contempt. This was problematic, because in its entire history, the House of Representatives had never rejected a recommendation for contempt. It looked like the president of CBS would go to jail for protecting a group of investigative journalists.

Now I also spent some time last week reading the transcripts of the debate that followed on the floor of the House of Representatives. And I have to tell you, it was incredible. It was an actual debate. People hadn’t really made up their minds, and actually discussed this. It was incredible to read Republicans and Democrats having an honest to goodness intellectual conversation on the floor of the House of Representatives about the nature of electronic media, broadcast, and the First Amendment. And ultimately, all the charges against Frank Stanton and CBS were dropped. So score one for the First Amendment.

Years later, in his will, Frank Stanton—for those of you who didn’t know—Frank Stanton had a substantial role in really helping to build the modern Kennedy School as we know it. And he provided the funding, in his will, to endow this lecture in memory of his friend and colleague, Dick Salant, the lawyer who loved journalism and fought for the First Amendment at every turn. And so today, we have the honor of hearing Jameel Jaffer give the Richard S. Salant Lecture on the Freedom of the Press. Jameel Jaffer is director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, and he’s been on the front lines of open records battles for more than a decade, including as the deputy legal director of the ACLU, overseeing the organization’s work related to national security. We have for you, at every table, at every seat, the ACLU’s pocket copy of the Constitution, so that you too can ask, “Mr. Trump, have you even read the Constitution of the United States?” (Laughter) Jaffer led the ACLU’s legal battle to secure the release of classified government documents related to drone attacks, leading last year to the publication of The Drone Memos: Targeted Killing, Secrecy, and the Law. His talk tonight is titled, “Government Secrecy in the Age of Information Overload.” This is a paradox indeed: secrecy, and yet we swim in more information than ever before.

The great paradox is that as we put more and more power in the hands of individuals, we’ve seen institutional power become more and more concentrated.

If I were giving you this speech 40 years ago, and I asked you to describe a computer, you would have described something that would fill one of these tables. A Cray supercomputer from the mid-‘70s was a mammoth thing. Its base price was almost 10 million bucks. It was only available to the world’s largest institutions. And today, we walk around with these mobile phones on our person, these incredibly powerful devices. They are so much more powerful than the supercomputers of 40 years ago that it’s almost like comparing oranges to Mack trucks. You just can’t even begin to compare them. We’ve put unimaginable power in the hands of individuals with these devices. But the great paradox is that as we put more and more power in the hands of individuals, we’ve seen institutional power become more and more concentrated. Not only do we have a handful of digital platforms that control the shape and space of the public sphere online, but we’ve watched government power become increasingly centralized, especially as it relates to information. And part of the story of government’s increasingly centralized control over information is related to terrorism.

I think decades from now, historians are sure to see September 11, 2001, as a moment the basic calculus of our national security shifted. The destructive power available to the wealthiest nation states, nuclear weapons, missiles, submarines, vast quantities of conventional arms, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of soldiers, those used to be the symbol of the nation state’s power. But increasingly, power is shifting to technologically equipped terrorist groups, revolutionary movements, criminal enterprises, murky online collectives, and even just isolated individuals with an internet connection. As these kinds of threats to our national security and the power of the nation state become more diffuse, the state has responded by centralizing power, by growing the intelligence gathering and the surveillance of the government by leaps and bounds. I’m sure many of you know, in 2010, The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its “Top Secret America” series, led by Dana Priest and William Arkin, which mapped out the dramatic expansion of secret intelligence in the United States.

Secrets beget secrets. Secrets compound themselves. The freedom of the press and the First Amendment are first and foremost about holding power accountable. It is my great honor to turn the podium over to Jameel Jaffer who, for many years, has led the fight to hold power accountable, and to bring greater transparency to our government. Please join me in giving him your rapt and complete attention. Thank you. (Applause)

Jameel Jaffer: All right. Thank you. Thanks for inviting me to speak this evening. And thanks Nicco for the kind introduction. It’s great to be here, it was great to have some time this afternoon to catch up with some of your fellows, got to see Andy Rosenthal and Wael Ghonim, and Alberto Mora, who’s one of the people I most admire. So thanks again for inviting me.

When President Obama famously promised that his would be the most transparent administration in American history, the more cynical among us were disappointed that the president had set such a low bar for himself. (Laughter) Despite the low bar, though, few people today—and certainly very few transparency advocates—believe that President Obama kept his promise.

President Obama gets credit, as he should, for releasing White House visitor logs, for reversing Attorney General John Ashcroft’s presumption against disclosure, for reforming the Justice Department’s rules relating to media subpoenas, and for releasing the Justice Department memos authorizing torture.

President Obama’s transparency record was not what we had hoped it would be, but unexpectedly it now seems relevant that President Obama didn’t routinely question the value of the First Amendment, demonize the press, or deliberately undermine the public’s confidence in it.

But in the assessment of many transparency advocates, the Obama administration was more notable for the extraordinary lengths it went to to control disclosures and manage public opinion about its decisions and policies. It withheld key legal memos about national security programs, disclosing them only when required to do so by the courts. It monitored journalists’ phone records and served them with subpoenas to force them to reveal their sources. It labeled one reporter a criminal coconspirator in order to justify a search of his emails. And it prosecuted more whistleblowers and leakers than all previous administrations combined.

Margaret Sullivan wrote in The Washington Post that, quote, “After early promises to be the most transparent administration in history, the Obama administration turned out to be one of the most secretive.” And James Goodale, former general counsel to The New York Times, said that President Obama’s record on press freedom and national security rivaled that of Richard Nixon.

Of course, many of those who criticized President Obama are now feeling wistful. President Obama’s transparency record was not what we had hoped it would be, but unexpectedly it now seems relevant that President Obama didn’t routinely question the value of the First Amendment, demonize the press, or deliberately undermine the public’s confidence in it.

And yet, there’s an argument to be made that President Trump is now delivering the transparency that President Obama failed to. Politico’s editor in chief, John Harris, didn’t fully embrace the argument but he explained it in this way, quote: “Ordinarily, if you want to know what’s going on inside the West Wing, you wait a couple years for Bob Woodward to write a book. You wait 10 years for somebody to write their memoirs.” But now there’s no need to wait. We’re getting the inside dope about the White House in real time. Michael Kinsley, in a special New York Times section inexplicably titled, “Say Something Nice About Donald Trump,” wrote this: “Donald Trump is running what might be the most transparent administration in history.”

Is he? Are we now entering transparency’s golden era? Is President Trump delivering what President Obama couldn’t, or wouldn’t? In a word, no. But I’d like to give this argument its due, and then propose a few reasons why I think we should reject it.

Let’s begin by acknowledging that we’re awash in the kind of information that would have been almost impossible to get hold of only a few years ago. First, leaks. To say that the Trump administration leaks like a sieve would be very ungenerous to sieves. (Laughter) Since President Trump took office, the media has overflowed with stories that couldn’t have been written without the cooperation of insiders—insiders who felt free, and perhaps even obliged, to disclose information that the administration couldn’t possibly have wanted them to disclose.

In The Atlantic, Jack Goldsmith writes, “We have never seen anything like the daily barrage of leaks that have poured out of Trump’s executive branch.” A few months ago, Republican staff of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security issued a report contending that during the Trump administration’s first 126 days, the media had published 125 distinct stories based on leaks of national security-related information. Some of the leaks concerned what are ordinarily the government’s most closely held secrets: the contents of surveillance intercepts, the workings of the foreign intelligence surveillance court, the substance of FBI interviews and the direction and findings of FBI investigations. Several of the stories quoted directly from President Trump’s calls with foreign leaders. A more or less random selection of the headlines: From The Washington Post: “Jared Kushner now a focus in Russia investigation.” From The New York Times: “Top Russian Officials Discussed How to Influence Trump Aides Last Summer.” From CNN: “Comey now believes Trump was trying to influence him.” And again from the Post: “Internal Trump Administration Data Undercuts Travel Ban.”

To say that the Trump administration leaks like a sieve would be very ungenerous to sieves.

In themselves, of course, leaks of national security information are nothing new. Max Frankel, who was then the Washington Bureau Chief for The New York Times, famously observed in 1971 that if the media were to stop disclosing putative national-security secrets, quote, “There could be no adequate diplomatic, military, and political reporting of the kind our people take for granted, either abroad or in Washington.” And we all know that news stories based on leaks were a fixture during the Obama administration.

But there are leaks and then there are leaks. Many of the leaks during the Obama administration were of a different quality than the ones appearing in the press now. They were calculated revelations by administration loyalists, probably senior officials, meant to bolster the administration’s public messaging, or to correct what the administration believed to be public misconceptions about its policies. “The leak,” said Henry Cabot Lodge, the ambassador to South Vietnam in 1963, “is the prerogative of the ambassador. It is one of my weapons for doing this job.”

Many of the leaks that appeared in the media during the Obama administration were of that character and pedigree. They reflected deliberate, strategic efforts by senior officials to shape public opinion about their decisions and their policies. They were “plants” rather than “leaks,” or they were something in between, what Columbia Law School Professor David Pozen has called “pleaks.”

A few years ago, I litigated a series of FOIA cases about the Obama administration’s use of armed drones to carry out “targeted killings” overseas. The administration argued in court that any disclosure on this topic would compromise national security. Meanwhile, officials fed information to reporters under cover of anonymity. ProPublica collected hundreds of news stories in which statements about the purported effectiveness or lawfulness of the drone program were attributed to unnamed government sources. In that context, officials were disclosing classified information in a concerted effort to influence public opinion. They disclosed information that cast the drone program in a favorable light, and they withheld information that didn’t.

On the whole, the leaks we’re seeing in the media now are very different. They don’t reinforce the Trump administration’s messaging, they contradict it. They don’t reflect a disciplined effort on the part of the Trump administration to shape press coverage of its policies. To the contrary, they offer narratives that compete with the ones the administration is pushing in its official communications. The executive may be many things right now, but unitary is not one of them. There is no official line, singular, there is a proliferation of official lines, and of many quasi-official lines too, with the result that we know much more about the White House than we otherwise might.

But the claim that the Trump administration is especially transparent isn’t based solely on the proliferation of leaks. There’s also the President’s Twitter account.

I don’t need to tell you that the @realDonaldTrump account is something entirely unprecedented, a spigot of presidential disclosures, a stream of presidential consciousness, what sometimes seems like a direct tap into the president’s brain. The president has tweeted 2,100 times since November 9; 1,366 times since January 20—an average of about 7 times a day. Each tweet has shed light on official decisions or policies, or at least on the temperament, character, and motives of the person most responsible for them.

We may not always like what we see, but the fact that we see it is something truly amazing. We’re privy to the president’s thought process. We’re witnesses to the waxing and waning of his passions, negotiations with foreign leaders, the shivving of political opponents, the flattering of allies, the elevation and humiliation of aides and secretaries. We are CC’d on the kinds of communications that the executive branch usually safeguards most fiercely. Brian Stelter told the Columbia Journalism Review, “It’s a raw, shocking use of media by a president, like he’s hosting a late night talk show, picking fights, getting even with enemies.” Stelter is right about that, but the “talk show” analogy risks understating the import and the implications of some of the president’s 140 character proclamations: the president’s first takes, his quick takes, his hot takes, not just presidential communications, but presidential deliberations. And not just presidential deliberations, but deliberations about foreign policy and national security, the kinds of communications that, were somebody to request them under the Freedom of Information Act, would be withheld on the basis of more exemptions than you could count.

It was through @realDonaldTrump that we learned that John Kelly would become the president’s chief of staff, that the president hadn’t taped his phone calls with former FBI director Jim Comey. And more recently, that the president had concluded that, quote, “Only one thing would work” against North Korea. The @realDonaldTrump account gives all of us access that even the most favored White House reporters could never even have dreamed of. From Politico’s John Harris: “You don’t have to wait for Trump to tell you what’s on his mind. To tell you who he’s angry at. What his vendettas are. Who he wants to pay back. All you have to do is wait until 10 to 6:00 in the morning.” Others have analogized President Trump’s twitter account to President Roosevelt’s radio addresses, and the analogy is apt in some ways. Between spring of 1933 and the summer of 1944, President Roosevelt delivered 28 radio addresses on topics ranging from economic conditions in the United States to the rise of fascism in Europe. Like Trump’s use of Twitter, FDR’s radio addresses were an experiment with an emerging communications technology. They were an effort by the president to appeal directly to the electorate, without the mediation of newspapers controlled by political opponents. FDR used his radio addresses to speak to Americans personally, even intimately, eschewing some of the formalities of his office and addressing his listeners as “you” or “my friends.” This is why Harry Butcher, the CBS reporter, labeled them “fireside chats.”

But the analogy to FDR’s radio addresses goes only so far. FDR’s addresses involved the recitation of prepared remarks; they were calculated rather than spontaneous. And without putting too fine a point on it, the tone of those prepared remarks was very different than the tone of President Trump’s tweets. President Roosevelt’s radio addresses were in large part an effort to bolster public confidence in American institutions, and in the viability of the American project during the Great Depression. They were meant to calm fears, not stoke them. Their overall message was the same one that President Roosevelt had conveyed in his first inaugural address, that the challenges confronting the nation were profound, but that America would “revive and prosper,” and that the only thing Americans had to fear was fear itself.

Perhaps the better analogy isn’t to FDR’s radio addresses but to Nixon’s tapes. It was actually FDR who introduced the practice of taping conversations in the White House; Nixon was only following tradition. He came to regret having followed it. But I mention the tapes here not because of the role they came to play in the Watergate investigation, or in Nixon’s resignation from office, but because of their content, which featured Nixon’s free-association commentary on issues both trivial and momentous. The commentary is raw, intimate, coarse, vengeful, petty, impulsive, and very often self-incriminatory, all adjectives that many would apply to President Trump’s Twitter feed. President Nixon’s biographer, John Farrell, said recently that historians would pore over President Trump’s tweets for the same reason they pore over President Nixon’s tapes, because they expose the, quote, “unvarnished presidential id.”

The kind of commentary that President Nixon once recorded surreptitiously, President Trump now broadcasts contemporaneously. Trump’s tweets are the Nixon tapes, the unvarnished presidential id, but livestreamed.

Nixon made his tapes for his own purposes, and not for public disclosure. They were secrets, not 140 character broadcasts. Nixon fired the attorney general, and the deputy attorney general, and fought all the way to the Supreme Court in an unsuccessful effort to prevent their release. But that’s exactly why Trump’s Twitter account is so extraordinary. The kind of commentary that President Nixon once recorded surreptitiously, President Trump now broadcasts contemporaneously. Trump’s tweets are the Nixon tapes, the unvarnished presidential id, but livestreamed.

They’re more than that, too. Where FDR’s radio addresses were one-way broadcasts, Trump’s Twitter account is interactive. Twitter allows the president to broadcast his messages to the public, but it also allows members of the public to respond to the president and to engage with one another. The responses themselves supply a kind of transparency, because they’re indicators of public sentiment about the president and his policies.

Now, they’re imperfect indicators. For the past few months the Knight Institute has been litigating a First Amendment challenge to the president’s practice of blocking people from his Twitter account, because of their expressed viewpoints. The essence of our complaint is that the president is turning a public forum into an echo chamber. Still, despite the president’s blocking of some of the comments, the comment threads associated with the president’s tweets do tell us something useful about how the public reacts to the president’s statements.

So, if leaks are proliferating, and the president is tweeting, why resist the notion that we’re entering transparency’s golden age? Why resist the idea that the workings of government—or of the White House, at least—are more visible to us now than ever before?

Let me offer a few reasons, apologizing in advance for their obviousness.

First, disclosure is generally to be celebrated, but it matters what’s being disclosed. Some of the disclosures we read in the press are valuable, others aren’t. Some of the president’s tweets are valuable, but many are not. They’re noise, at best. Last week, Jack Shafer wrote in Politico that a great number of the president’s tweets are meant not to inform the public, but to reset the news agenda. That’s plainly right. These tweets are better conceived of as distractions rather than disclosures. Of course at some meta level, the revelation that the president is trying to reset the news agenda is itself a disclosure of something interesting and important. But that meta-disclosure comes at a cost. Increasing the noise-to-signal ratio, which is what the president is sometimes doing, makes it more difficult for us to have the conversations we really need to have.

In a paper called Is the First Amendment Obsolete? Tim Wu, another Columbia Law School professor, observes that the seminal First Amendment cases of the last century were focused on the threat of government censorship. The implicit assumption of these cases was that speakers were scarce and that speech needed protection. There’s no such scarcity today. For anyone with even limited means, it’s easy to broadcast a message to millions of people. Speech is cheap, and speakers are abundant. Listener attention, on the other hand, is harder to come by. It used to be difficult to speak, but now it’s difficult to be heard. And that’s why, as Professor Wu notes, there’s now an entire industry whose business model is the sale and resale of human attention.

Zeynep Tufekci has written about this, too. She notes that, in an age in which information is plentiful and listener attention is correspondingly scarce, the most effective way to censor an inconvenient fact or idea is not to prohibit its disclosure, but to bury it with other information. And in this context, disclosure is a form of suppression. An information glut and an information famine can amount to the same thing. We can put that a different way. For those concerned about the dissemination of information and knowledge, the problem of the twentieth century was the problem of government-enforced silence. The problem of the twenty-first is not silence, but noise. We should be careful not to mistake noise for transparency.

Disclosure is generally to be celebrated, but it matters what’s being disclosed. Some of the disclosures we read in the press are valuable, others aren’t. Some of the president’s tweets are valuable, but many are not. They’re noise, at best.

Second, there’s also an important difference between discretionary disclosures and mandatory ones. To the extent President Trump is disclosing information through his Twitter account, the disclosures are purely discretionary, and, not unrelatedly, they’re selective and incomplete. Selective transparency is, of course, nothing new. I already mentioned the Obama administration’s messaging campaign relating to the drone program, which was a triumph of strategic, cherry-picked disclosure. Still, if we celebrate disclosures, we shouldn’t lose sight of what’s still being withheld. It’s worth asking whether the tidal wave of leaks and tweets carries with it the information we need most.

The White House produced an eight-minute video highlighting the administration’s efforts in Puerto Rico, but a few days ago, important statistics about the recovery effort disappeared suddenly from FEMA’s web page, restored only after reporters noted and criticized their disappearance. Two weeks ago, the administration released the outlines of its proposal to overhaul the tax code, but President Trump has yet to release his own tax returns. And for the past few months the Knight Institute has been litigating for the release of visitor logs for the White House, Mar-a-Lago, and Trump Tower, the idea being that the public should know who has access to the president. You may remember that that issue was the subject of litigation during the Obama administration too, but the administration ultimately agreed of its own accord to release White House visitor logs on a regular basis, and it did. Together with open government groups, we sued when President Trump discontinued the practice, but for now these records are still being withheld.

So by all means, let’s celebrate disclosures, but let’s not forget what’s being stuffed in the memory hole. Just yesterday, in the Columbia Journalism Review, Mathew Ingram noted that the president’s loquaciousness on Twitter has been accompanied by, quote, “A concerted effort to end-run the mainstream press.” President Trump has held fewer press conferences than any recent president. His administration prefers to give briefings off the record. The president’s strategy is not to supplement other forms of disclosure, but to replace them.

Third, the abundance of leaks will almost certainly be short-lived. The day after The Washington Post published leaked transcripts of President Trump’s phone calls with the Mexican president and Australian prime minister, Attorney General Jeff Sessions condemned what he called the “culture of leaking” and he threatened to prosecute those who leak classified information and perhaps also the reporters who publish it. He said that the Justice Department had more than tripled the number of active leak investigations.

It’s too early to say where all of that will lead. But it’s worth remembering that the 1917 Espionage Act was drafted very broadly, and that an administration committed to cracking down on leakers or reporters wouldn’t encounter a great deal of resistance from the text of the statute. On its face, the Espionage Act doesn’t distinguish between ill-motivated leakers who supply classified information to foreign intelligence services, and public interest-minded whistleblowers who disclose evidence of government abuse to the media. The Act reaches reporters and publishers, not just whistleblowers and leakers. And the Reality Winner case, now pending before a district court in Georgia, is unlikely to be the last of the Trump-era Espionage Act prosecutions. Chelsea Manning, by the way, probably would have had interesting and important things to say about those topics, but I digress.

Finally, President Trump’s daily broadsides against the motives and reliability of the press are, among other things, an assault on transparency. We value transparency because we believe that an informed public will be better able to understand and evaluate public policy, advocate for necessary reforms, and hold elected officials accountable for their decisions. But none of that is possible if large segments of the public don’t believe that the facts being made public are actually the facts. The president’s campaign against what he calls “fake news” undermines the public’s faith in the media, makes large segments of the public distrust provable truths, and makes it more difficult for us to have conversations across political divides. Carrie Cordero, a former Justice Department lawyer, captured the president’s apparent strategy in a post on Lawfare: “The president has launched a consistent, sustained effort to discredit the media, with the goal of minimizing the role of America’s free press and establishing himself, instead, as the one true source of information to be believed.”

We value transparency because we believe that an informed public will be better able to understand and evaluate public policy, advocate for necessary reforms, and hold elected officials accountable for their decisions. But none of that is possible if large segments of the public don’t believe that the facts being made public are actually the facts.

In February the president labeled the media the “enemy of the American people.” Last week the president wondered, apparently seriously, why the press should be allowed to report what it wants to, and he suggested that NBC should be deprived of its broadcast license. These kinds of statements are intended to weaken our confidence in the institutions most responsible for revealing facts about the government, and they’ll have the effect, over time, of delinking revelation from political action, transparency from accountability. Don’t forget that democracy depends entirely on the readiness of individuals to take political action in response to disclosures about government. But of course, no one will be motivated to take political action on the basis of facts they don’t believe to be true.

So I don’t share others’ excitement about the alleged golden era of transparency. To the contrary, it seems to me that transparency, and the values tied up with it, face dangerous new threats. We have to remember that we prize transparency not for its own sake, but because of its connection to other democratic values, like reasoned political discourse and official accountability. Disclosure can serve these values, but it can also undermine them. It would be difficult to make the case that President Trump’s purported transparency is serving these values. If this is transparency at all, it’s a transparency we should distrust and interrogate rather than applaud. Thanks again for the invitation. (Applause)

Nicco Mele: We’re going to take a few questions, we have some microphones. So please, raise your hand, and we’ll come to you with a microphone. I’m going to start by asking—you talk about the role of noise in obscuring the signal. And that is quite provocative, Is the First Amendment Obsolete? But to what extent do you think the courts are susceptible to that level of noise?

Jameel Jaffer: Do you mean do I worry that the courts won’t—rephrase your question, Nicco?

Nicco Mele: It strikes me that noise is a problem in the political sphere.

Jameel Jaffer: Right.

Nicco Mele: But is it really a problem in the judicial?

Jameel Jaffer: No, well, that’s not my worry with the courts. I do worry about how the courts will address these issues, not because they’re overwhelmed by noise, but because they inherit a legal framework that was built for a different set of threats. You know, the legal framework that was created mainly in the 1960s and ‘70s, through cases like the Pentagon Papers case, or New York Times v. Sullivan, or Brandenburg [v. Ohio]—the big hits of American free speech tradition, those are cases that had a different set of threats in mind. They were cases in which the threat came from the government, rather than private actors. They were cases in which the form of the threat was censorship, rather than say, flooding. And I do wonder how the courts will respond to this new set of threats. President Trump’s Twitter account may be part of it, but in the grand scheme of things, these threats go far beyond this administration, and the trends that I sort of alluded to, I think are not connected to this administration. They have to do with new technology, they have to do with the business models of the social media companies, they have to do with the fact that private entities now control entry to the public square. I worry about how the courts will address those questions. They’re hard questions. The noise issue, I think, is an issue more as you say, in the political sphere.

Nicco Mele: I have another question for you. Tell us a little more about the status of your litigation on the president’s Twitter account, about why you decided to pursue that with the blocking, and where it stands.

Jameel Jaffer: Sure. So, there is a well settled First Amendment principle that in a public forum, or what’s called a designated public forum, the government can’t silence or exclude people based on viewpoint. So that’s well settled. The question is whether the president’s Twitter account is a designated or a limited public forum. The question of government officials’ social media accounts and their status under the First Amendment is an issue that’s arising only now, with respect to President Trump, but also with respect to other political leaders all over the country. So this is not an issue that has been litigated a lot in the courts, but it’s an important issue because public officials now engage their constituents mainly through these social media channels. These are really a replacement for old forms of engagement that existed in the pre-social media world. So if the most important way that officials engage with their constituents is through social media, and officials have at their disposal this tool of blocking people they disagree with from those channels, it has far reaching implications for democracy. So we saw this case as, in part, a way of establishing, I hope, good law on that question of when a public official’s social media account becomes subject to the First Amendment in this case, and also, reaffirming this crucial First Amendment principle, that whatever the First Amendment means, it certainly means that the government can’t exclude you from a conversation about government and policy on the basis of your disagreement with the government’s views. So that’s sort of the idea of the case.

I guess I should also say that we’re motivated in part by the effect of these exclusions on the people who’ve been excluded—but also motivated by the effects of these exclusions on the forum that’s left behind, because the forum that’s left behind is now a forum that’s been purged of many dissenters. So if you look at the comments to President Trump’s tweets, you will see a skewed set of responses—most of those responses come from supporters. And you might, if you are looking to this forum as a means of evaluating the public’s attitude towards the president’s policies, get the misimpression that there’s near uniform enthusiasm for President Trump’s policies. And that’s not the case. So part of the point here is to push back against the creation of this misleading echo chamber [created] by the government.

As to the status of the case, the government filed, expectedly, a motion to dismiss on Friday of last week. They argue that this is not government speech at all, it’s not official speech, it’s the president’s personal account, which is what they’ve been saying in the media. They also argue that even if this is unconstitutional, even if the president is acting unconstitutionally, the court lacks authority to enjoin the president. And they rely on a long list of cases in which the courts have stayed their hand, after having been asked to enter injunctions against the president. I don’t want to get into too many of the weeds here, but here the government has conceded that other officials have access to the account, so there may be ways for the court to resolve the question without reaching this big question of separation of powers.

Donna Brazile: I have the mic. (Laughter) First of all, thank you so much Mr. Jameel, I’ve actually taken three pages of notes, and I was surprised that your lecture—

Jameel Jaffer: That’s longer than my lecture.

Donna Brazile: Yeah, but it interested me, because of the way you framed the disclosures that we see every day as possible distractions. So I took notes, and I’ll go back and figure it all out. That’s why with Professor Patterson here, I can always request an appointment. (Laughter) So recently, the European Union told some of our social media platforms, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc., that they had to rid their platform of hate speech, or face legal consequences. Now I know what hate speech is all about, at least I think I know. But, what if we tried to apply that here? Can we do it here in this country? And remember, Al Gore invented all of this when the internet came about— but now that we know what can happen in these platforms, the social discord, the divisions, disinformation, pitting Americans against each other, can we, in this country, see a day where there will be legal consequences of putting this kind of hate speech on their platforms?

The platforms are not any better situated than the government is to decide what’s hate speech, and what’s not.

Jameel Jaffer: Well, under existing First Amendment doctrine, I think it would be hard for Congress to require the platforms to take down hate speech. As you know, the First Amendment is very broad, it protects even hate speech. And you know, in my view, that’s a good thing that the First Amendment has been construed so broadly. Now that doesn’t mean that the platforms themselves can’t take some of this stuff down. And the platforms have been taking some of this stuff down. That could be a good thing. But, it’s a complicated question, because deciding what counts as hate speech is difficult. It’s one of the reasons why the courts have not allowed the government that power. But the platforms are not any better situated than the government is to decide what’s hate speech, and what’s not. And once you accept that the platforms are going to be exercising that authority, you probably have to accept that they’re going to get it wrong sometimes, and maybe their motivations aren’t always going to be the right ones.

Now on balance, you may say well, it’s still better that they try, and many people think it is. They think it’s better that Facebook and Twitter, given that they have this authority, and given the damage people think some of the speech has done. Maybe it’s better that Twitter and Facebook own this responsibility of policing the platforms. But if you’re going to go down that road, I think you need, you would want, more transparency from the platforms than they have been willing to provide so far about how they make those determinations, who makes those determinations. You would probably want some form of process that the platforms, for the most part, have not adopted. If you’re taken off the platform unfairly, can you challenge it? Who’s going to hear your challenge? Those kinds of questions, I think, would have to be answered.

You know, I’m sort of ambivalent about all of that. On the one hand, I do think that some of this speech has done a lot of damage. On the other hand, I worry that the cure will be worse than the disease, and that these platforms will end up policing the public square in a way that is even more damaging to our democracy than all this speech that you’re referring to has been.

Nicco Mele: Do you think that the volume and permissiveness of the digital platforms in allowing this proliferation of speech changes the equation at all?

Jameel Jaffer: Well it could change the equation in a few different ways. One question is just about liability, right? So there’s a statute that protects the platforms for posting the content of third parties. So ordinarily, if Facebook were treated like The New York Times, Facebook would be liable for a lot of speech that it’s not liable for right now. One justification for extending that immunity to the platforms was that the platforms were operating as, for the most part, neutral conduits of content created by third parties, policing only at the margins. Now things are a lot more complicated. The platforms routinely decide, if not what to take off the platform, what to leave on, at least what content to privilege, and what content to subordinate. So they engage in what looks more like editorial decisions every day, right? So, this is not an answer to your question. But I think that part of the reason all of us are struggling with what is the right answer to the platform problem, is that the platforms look sometimes like the phone companies, and sometimes they look like The New York Times. And depending on what realm they’re operating, they may look more like one than the other. And it’s very hard, we don’t have a legal framework that seems to make sense for this hybrid model that the platforms are right now.

From the audience: Following up with the platform question, a lot of the discussion now is in the realm of the advertiser in influencing what Facebook and others are doing. If you were the counsel to Facebook, how would you advise them?

We don’t know how information is being shared, or why it’s being shared, why one thing goes viral and another thing doesn’t. We don’t know who is contributing to the public square, we don’t know which foreign intelligence services are contributing to it.

Jameel Jaffer: Don’t take ads from foreign intelligence services. (Laughter) That’s my advice. No, I mean I think this sort of goes back to the transparency point. And there are people here, amongst others, who are working on this question. But I think this question of what the platforms should make public, is a very important question. Because I think right now, we have very limited understanding of what the infrastructure is under what has become our public square. Like we just don’t know how or why some people’s speech is being privileged, and others is being subordinated. We don’t know how information is being shared, or why it’s being shared, why one thing goes viral and another thing doesn’t. We don’t know who is contributing to the public square, we don’t know which foreign intelligence services are contributing to it. Answers to those questions, or at least some form of an answer to those questions, might be necessary before you know what form of regulation might make sense, right?

From the audience: What I’m trying to get at is not so much the Russian infiltration into the system, as much as the average advertiser, who is then influencing what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable in the form of hate speech.

Jameel Jaffer: Yeah. I’m not sure I have an immediate answer to that question. I mean there is a whole set of transparency/accountability questions relating to microtargeting, right? You see ads that I don’t see, and—I’m stealing an idea that Wael was just describing to me this afternoon—but nobody sees the whole picture, right? And if you want to evaluate the health of the public square, you kind of need to see the whole picture, you can’t do it by looking through these narrow windows. So, this is maybe a very partial answer to your question, but I think it does relate to transparency, and what the platforms should disclose, or what they should be required to disclose.

From the audience: Thanks so much for your talk. I’ve been reading the biography of Archibald Cox.

Nicco Mele: Conscience of the Nation.

From the audience: Exactly, it’s a really good book.

Nicco Mele: Excellent.

From the audience: I’ve been struck by his integrity, the deep anchors in his personality that lead him to act always out of principle. And it has also appeared to me that there must be civil servants inside the administration who are deeply concerned about the corruption of everything they hold dear, and that there may be a tsunami of leaks coming in the other direction, that are real leaks that are actually real secrets. What’s your assessment of that situation?

Jameel Jaffer: Well I’m sure you’re right that there are people in the administration who are uncomfortable with—I mean uncomfortable probably doesn’t begin to describe it—but uncomfortable with some of the policies, and the direction that the administration seems to be taking on some issues. And I know that there are many people inside who have struggled with what’s the right thing to do in that situation? Do you stay and hope to mitigate what you perceive to be colossal damage that might be caused by these policies? Or do you leave, and try to use your leaving as a way of maybe moving the administration towards raising concerns about some of the policies, and raising public awareness, and moving the administration maybe marginally? I think that’s a hard question for anybody in the inside. I don’t know if you were getting at sort of the deep state question, right?

On the one hand, you want the career public servants to resist, where resistance is appropriate. But anyone who knows anything about the history of military coups in the rest of the world has to be nervous to see that the resistance is coming, at least in part, from the CIA, or the FBI, or the Defense Intelligence Agency. So I haven’t worked out, at the end of the day, if I feel good about that or not. That too I think is a hard question. Yeah.

I do think that surprisingly, to me, one of the people who’s written most insightfully about both those questions is Ben Wittes at Lawfare. I say surprising because I usually disagree with him, but he’s always insightful, but I think especially insightful on those questions.

From the audience: Hello, I’m in the MPA/ID program. And I’d like to touch on some of the things said earlier about the First Amendment. The idea that the Second Amendment was created in a world with muskets, and it’s kind of understandable that anybody can carry around a musket. Now we have all sorts of weapons, and we have to really find a way to limit the use of that. And in that same world, the First Amendment was created, and it was created in a world where speech was as far as your voice would carry, and now we’re in this world where it’s probably like the große lüge, what Hitler was talking about in Mein Kampf of telling the biggest lie that’s so simple, that if you were to repeat it, then it becomes a truth. It’s the weaponizing of words in a way that we’ve never seen before, where you can say something so big, and so bold, that that’s all the people can hear, right? And if you say that to enough people, then you end up with violence, or disgust, or any other sort of emotion. Maybe you can speak to how we might go about regulating that, in that context? Where every time you tell a lie, it’s like yelling “Fire” in a theater?

Jameel Jaffer: Yeah. So, you know, if you look back at these Supreme Court cases from the last century, the ones that involved prosecuting suspected anarchists, or prosecuting suspected communists, the atmosphere in the country at the time of those cases was one in which the threat was thought to be uniquely serious. And the argument was always made that, at least in the ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘70s, that these protections might have made sense in a different political context, in a different era. But now, the threat is different, and much more serious. And you know, with the benefit of hindsight we see, well, those threats may well have been significant threats, but it was probably better that the court held the line to the extent it held the line. Right now, I think a lot of us feel like we face this new threat, I mean it is definitely a new set of threats. And they seem unusually serious. So, a natural instinct is the instinct that we saw in those earlier cases. The instinct is, well, let’s relax our protection for these freedoms, because we’re facing a different kind of threat. And I don’t want to rule out the possibility this is a different enough kind of threat, the threat here is different enough, and serious enough, that we should think about adjustments. I don’t want to rule that out, but I think we should go into that conversation with some understanding of that history, and some understanding of the fact that we’ve been through that thought process before, right? And in hindsight, it has always seemed like the right decision was to protect those liberties, rather than to yield them, because of some seemingly uniquely serious threat.

I do think that the First Amendment as we know it now was built in an era in which nobody had these threats in mind.

So, that’s one thing. The other thing is, I do think that the First Amendment as we know it now was built in an era in which nobody had these threats in mind. And it doesn’t make sense not to rethink whether those protections are still the right ones, whether they need to be extended in some ways, whether they need to be understood differently. There is this process going on now, I think with the Fourth Amendment, the Supreme Court has heard a number of cases over the last decade, one called Jones, which involved location tracking, another one called Reilly, which involved warrantless access to cell phones. And the court in those cases has rethought the significance of the Fourth Amendment, in light of new technology, or rethought old precedents, in light of new technology. There was another case that the ACLU has before the court, it’s going to be argued at the end of November, called Carpenter, involving location tracking over time. This is access to cell site location information. The government gets this information without a warrant; it’s very granularly detailed information about where you were over a several week period of time. And the question is, does warrantless access to that kind of information trigger the Fourth Amendment? Does it count as a search under the Fourth Amendment? And there again, the fact that the court has taken this case is, I think, a sign that the court is reconsidering its precedents in light of the capacity of new technology to invade Constitutional rights in new ways.

I expect that we’ll see something similar with the First Amendment. There was this case, the opinion was released just a few months ago, called Packingham, in which Justice Kennedy wrote an opinion that was largely about the role that social media now plays in our democratic discourse. So, the concepts we’ve been talking about are not foreign to the Supreme Court. And I would anticipate that the court will now probably hear a series of cases over the next decade that will require it to reconsider its analog era precedents in light of digital age technology.

Nicco Mele: Other questions? Cris?

Cristine Russell: Yes, thank you for your remarks. Could you elaborate a little bit on your comments earlier, using the words excitement about the golden age of transparency, or celebrating the disclosures in terms of President Trump’s daily extraordinary number of tweets? I’m not quite sure of the context in which you were using those words, or what did you mean by that? Who would be the people that were celebrating these tweets because they simply downloaded thoughts on a daily basis, some of which have public policy and government implications?

Jameel Jaffer: Yeah. Well if you Google the phrase “Most transparent administration in history”—if you Googled that phrase a year ago, you would have found thousands of hits relating to the Obama administration because Obama—I’m sure he regretted it—but he used that phrase in describing what his administration would be. And then civil libertarians complained constantly that his administration was not living up to that promise. But if you Google it now, you’ll find mixed in with all of those hits, a lot of news articles in which people wonder at least, and sometimes contend—I mentioned a couple of these people—some of them contend that the Trump administration is providing a kind of transparency that is valuable. And to be honest, in the first few weeks or even months of the Trump administration, I had that view too. I thought not that they made a deliberate decision to be the most transparent administration in history, and are now living up to their promise, but I thought the combination of the leaks and the Twitter account, they do really make a difference, and we do know much more about this administration than we did about the last one. We know a lot more about what they’re thinking about doing, we know about the dissent within the administration, we know about policies they considered and then rejected. I mean all of that stuff is not stuff that we would have gotten about the Obama administration, which was very, very disciplined.

I would anticipate that the court will now probably hear a series of cases over the next decade that will require it to reconsider its analog era precedents in light of digital age technology.

But over time, my view of all of this information changed. I now feel like the downsides may outweigh the upsides. The noise is distracting us from having conversations that we really need to have, and part of President Trump’s strategy is to distract people from the conversations that they’re having, and move them over to conversations that he would prefer them to have. And as a political strategy, that’s easy to understand, but I don’t think it’s healthy for the rest of us.

Nicco Mele: Last question, Howard.

Howard Cohen: Hey there, thanks so much for being with us. Just want to go back to the current lawsuit involving Twitter. When you think about all the lawsuits that Trump has been involved in as a businessman, he always had the upper hand, having more resources behind him. But today, he’s the president of the United States. What is it like to go up against him? Do you feel that in a sense, you are the weaker player, or the stronger player in this lawsuit?

Jameel Jaffer: So I spent most of my ACLU career litigating national security cases, right? And a national security case is almost impossible to win against the government. (Laughter) So, one nice thing about litigating a First Amendment case is that it’s conceivable that we could win, you know? So that effects my attitude towards this litigation. But one of the interesting things that happened in this case was, we filed suit—ordinarily in this kind of suit, the government would move to dismiss, and if we survived the motion to dismiss, we would move onto discovery. And my sense is that the Trump administration and the Justice Department were very worried about what discovery would look like in this case, that they didn’t want us to depose White House officials, they didn’t want us to depose Scavino, for example, who’s the social media director. And that they didn’t want us to submit interrogatories that the White House would have to answer. And Judge Buchwald, who is overseeing the case in the southern district of New York, urged the parties to enter into a joint stipulation of fact, to avoid the necessity of discovery. And the administration agreed to that, and we submitted a joint stipulation of fact in which the president doesn’t contest that he blocked our clients on the basis of viewpoint, the government doesn’t contest our description of the way that Twitter works, doesn’t contest the way we have described the injuries to our plaintiffs. So we now have this factual record, which ordinarily would have taken a year to create probably, through adversarial discovery. We have this factual record that the government has agreed to, and it took us just a few weeks. So, that’s all to say that the case so far has unfolded in an unexpected way. And I’m sure that there are many surprises in front of us. The immunity question may turn out to be one of the focuses of the litigation. And that makes the case interesting and important for a reason completely different from the one that motivated us to file it in the first place.

Nicco Mele: Jameel, what troubles you most about the current landscape?

Jameel Jaffer: Well, I just spent the last 45 minutes talking about Trump, but not Trump, actually. (Laughter) I think that a lot of the biggest threats to the First Amendment come from deeper trends. When Columbia University and the Knight Foundation set up the institute that I now direct, they set it up long before Trump was on anybody’s radar screen. They set it up with these deeper trends, like the rise of the social media companies, the privatization of the public square, the emergence of the surveillance state, the emergence of transnational transparency activists like Julian Assange. Those trends present very difficult and complicated questions for the First Amendment. And again, the legal framework we’ve inherited is one that was created in a time when nobody had any of this in mind. And I think those challenges are going to be with us long after the Trump administration is gone.

Nicco Mele: And my last question, what makes you most hopeful in the current landscape?

Jameel Jaffer: I have been very impressed with the reaction of many Americans to some of the Trump administration’s more unconstitutional policies. Because I work on the First Amendment, we talk about, amongst other things, hate speech of the kind that was on display in Charlottesville. When you see people in white robes and white hoods parading around, chanting the things that those people were chanting, I think there’s a moment in every First Amendment lawyer’s, day, when you wonder, does this really make sense? Does it really make sense to protect all of this? I mean when I see that stuff, that’s my first reaction. But I was very impressed by the reaction of civil society to that grotesque event, you know? So many political leaders spoke out against it in unequivocal terms. Republican political leaders felt obliged to distance themselves. The heads of all the major tech companies came out and condemned white supremacy and white nationalism, and condemned the speakers who had organized that event. And there were these counterdemonstrations in cities all over the country. There were tens of thousands of people at the rally in Boston. And if you believe that the First Amendment should protect all of this speech, then you presumably believe it because you think that at the end of the day, people will arrive at the right answer. And so, it’s a great relief to me to see people condemning that stuff, and coalescing around ideas that I think are better ones, and more defensible ones.

Nicco Mele: Thank you again to Jameel for your hard work on behalf of this country. Thank you very much. (Applause)