A new paper by Joanna Jolly, Joan Shorenstein Fellow (spring 2016) and former BBC South Asia editor, examines the increased coverage of rape in India’s English-language newspapers following the infamous 2012 gang rape in Delhi, and whether this coverage led to policy change.

India’s English-language newspapers play an agenda-setting role in the country. Jolly finds that although the topic of sexual assault has received more space in these publications in recent years, the coverage is often problematic: sensationalist, dependent on social class and caste, and rife with stereotypes about the causes of sexual assault. After public protests and editorials from the press, the Indian government established a committee to examine the country’s laws and attitudes toward women, producing an extensive report – yet the resulting media coverage was cursory, and the government has yet to enact suggested reforms. Jolly provides recommendations for how the Indian media and the government can work to improve conditions for women, addressing problems that are rooted in patriarchal structures. The paper also highlights the importance of sexual violence reporting in shaping public opinion and policy.

Read a condensed version at Columbia Journalism Review, “Rape in India: Is the English-language press falling back on stereotypes?”

Warning: This report contains graphic language about violent subjects, including descriptions of rape.

Listen to Jolly discuss her paper on our Media & Politics Podcast:

Introduction

On the morning of December 17, 2012, reports began to filter into Delhi’s newsrooms of a rape that had taken place in the city.[1] Police officers, the main source of information for these types of stories, told journalists that a student in her 20s and her male companion had been attacked by a group of men inside a moving bus before being thrown from the vehicle. The girl was said to have been gang raped. The couple had been returning from watching a movie at Select City Walk Mall, an upmarket shopping center in an affluent South Delhi suburb.

The crime reporter for The Times of India, India’s largest English-language newspaper with a daily readership of more than 3.2 million,[2] took the details to his editor and asked how much copy he wanted. A short version of the police information had already been published online. For the print edition, rape stories tended to be restricted to 300 words for the city pages, buried deep in the newspaper. Rarely did they make it onto page 1. To the editor, three facts stood out: the girl was a student, she had been to an upmarket mall, and she had been watching an English-language film, “The Life of Pi.” He told the crime reporter to write 500 words for a page 1 lead.[3]

Although the editor believed the story would resonate with his readership of middle and upper-class city-dwelling Indians, neither he nor the crime reporter had any idea how massive the public response would be. On the day the story was published, protesters had already begun to gather on Delhi’s streets to demand action against sexual violence.[4] As details of the brutality of the attack emerged, the protests intensified, spreading to other cities and sometimes leading to clashes with the police. Violence against women, and in particular rape, had a “sudden and gigantic prominence.”[5] Thirteen days after the attack, the victim died from her injuries. The Indian government came under immense pressure to address the protester’s demands: to tighten rape laws, to improve policing, and to address the reasons behind the seemingly high incidence of sexual violence in India.

As the English-language press continued to report on the progress of the rape investigation, they remained at the forefront of these demands, appearing to operate hand-in-hand with the protesters. For weeks, publications devoted several pages each day to the case and the protests, reinventing themselves as “rape-reporting vehicles.”[6] Some newspapers ran campaigns to have certain aspects of the law changed. Reporters wrote stories about cases that bore similarities to the December 2012 attack, and editorials demanded action and change.

More than four years after the Delhi rape, this paper examines India’s English-language press coverage of sexual violence, and considers how it shaped both public opinion and policy. Through interviews with journalists and editors and data analysis of the reporting in four prominent English-language newspapers, this paper explores the decisions and choices made in the coverage. These choices need to be studied seriously as it is well-recognized that sexual violence reporting can be hugely influential, with “stereotypes even becoming embedded in the judicial system.”[7] Reporters and news publications have the ability to shape the way people think about rape, as well as “how they receive rape victims, rapists and those accused of rape.”[8]

India’s English-Language Press

Unlike European and American newspapers which have been in decline for over a decade, India’s print sector remains remarkably buoyant. India is home to the world’s fastest growing newspaper market[9] with a total readership of more than 300 million.[10]

India’s English-language press is widely regarded as holding the leading position in the political, social and cultural life of India’s urban centers.

The most popular newspapers are local-language publications; with the Hindi daily, Dainik Jagran, pulling in the highest audience of 16,631,000 readers.[11] The Times of India tops the list as the most read English-language paper with 7,590,000 readers,[12] followed by the Hindustan Times with 4,515,000,[13] The Hindu with 1,622,000[14] and The Indian Express with 278,243.[15] The most read English-language news magazines are the weekly India Today with 1,634,000 readers[16] and Outlook with 425,000.[17] (The smaller English-language news magazines mentioned in this paper, the weekly Tehelka and the monthly Caravan, have a print circulation of 90,000[18] and 20,000[19] respectively.)

India’s English-language newspaper industry thrives in part because of a fast-growing English-speaking population, the low cost of production and delivery, and slow internet news penetration.[20] It’s a business heavily funded by advertising[21] with some publications, in particular The Times of India and the Hindustan Times, promoting the practice of “paid news” in which favorable articles are published in return for money.[22]

Despite reaching a smaller audience than India’s regional-language newspapers, this paper deals only with the English-language print media’s coverage of sexual violence. India’s English-language press is widely regarded as holding the leading position in the political, social and cultural life of India’s urban centers.[23] The publications are read by India’s educated and moneyed classes, and as more Indians aspire to join the urban middle-classes, their reach continues to grow.[24]

They were the first to identify the December 2012 rape as a story that would resonate with their readership and subsequently led the coverage and demands for change. According to the editor of the news magazine Caravan, Hartosh Singh Bal, the English-language media “sets the agenda for reportage on a number of issues, certainly the issue of sexual violence.”[25] Therefore, although an examination of Indian-language newspapers would result in a more detailed and comprehensive study, there is value in examining the English-language coverage because of its influential role in Indian society.

Regulation of Reporting on Sexual Violence

Before exploring how Indian newspapers cover rape, it’s important to examine the current regulations regarding sexual violence reporting in India. The only legislation restricting media coverage is section 228A of the Indian Penal Code, which prohibits the press from disclosing the name of a victim of sexual violence or providing information that could potentially lead to their identification. Breaking this law could lead to a fine and imprisonment for up to two years, though a victim can be named under special circumstances which include when they or their next of kin give permission.[26] The Press Council of India – an autonomous statutory body established in 1966 to safeguard the freedom of the press and build a code of conduct for newspapers and journalists[27] – also prohibits the naming or photographing of victims of rape in its “Journalistic Conduct Norms.” However, the council is a largely toothless body that does not give any explicit guidance on how sexual violence should be reported. While it can criticize publications that fail to follow its code, it does not have the power to penalize those found guilty of malpractice.[28] Media-watch websites, such as The Hoot, publish a journalist’s guide to rape reporting,[29] outlining the law and voluntary guidelines on the representation of rape victims, but it is not clear whether newsrooms regularly refer to these resources.

In practice, reporters working on sexual violence say guidelines and codes of conduct are rarely discussed.

In practice, reporters working on sexual violence say guidelines and codes of conduct are rarely discussed. “Nobody really tells you,” said Smriti Singh, a former legal reporter for The Times of India in Delhi. “Half the time editors don’t really know what the guidelines are. The onus is on the reporter and if you’re on the beat you pick up things,” she said.[30] This lack of training is normal practice within Indian media where new employees are rarely briefed on ethics.[31] “To the best of my knowledge, no Indian newspaper has a code on how [rape] cases should be handled,” said Praveen Swami, national editor for The Indian Express and a former associate editor of The Hindu. “There are no guidelines about what kind of processes should be in place to ensure respectful and accurate reporting, to make sure details invasive of privacy are not divulged.”[32]

In the case of the December 2012 rape, section 228A of the Indian Penal Code was generally adhered to, though a number of reporters interviewed say that by identifying the victim’s family and their location, newspapers came close to breaking the law.[33] Throughout the coverage the victim was identified by code names, the most popular of which was “Nirbhaya” – which translates as “fearless” or “Braveheart” – which was first used by The Times of India and later adopted by the government. Eventually, the rape victim’s mother asked for her real name – Jyoti Singh – to be used, saying she was not ashamed to name her.[34] Privately, reporters said that although in the majority of cases section 228A is not violated, they feel editors would break the law in the case of an exclusive that could increase sales.[35] In this regard the media is not alone in being accused of a sometimes patchy adherence to the legislation. Press reports show that members of the judiciary also break IPC section 228A and name rape victims, seemingly without consequence.[36]

Covering the Story

A Trigger Event

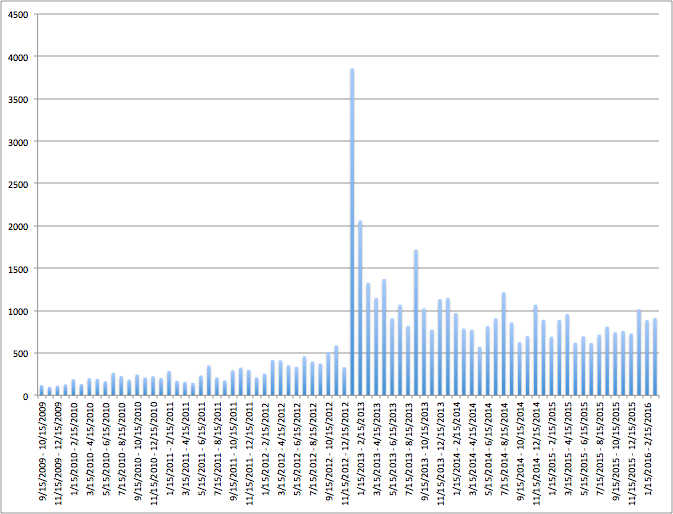

The widespread, passionate and prolonged public reaction to the December 2012 Delhi rape was unprecedented in India. A data analysis of rape coverage before and after the incident gives a clear picture of the impact it had on reporting. This paper analyzed the four English newspapers in India that are determined to have the most influence in terms of reach and circulation: The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, and The Indian Express.

A keyword search for <rape> OR <gangrape> OR <gang rape> was conducted in Lexis Nexis in these four newspapers for every month between September 15, 2009 and March 15, 2016 – exactly 39 months since the Delhi gang rape and 39 months prior to it. Not surprisingly, it reveals a huge spike in rape reporting at the point of the Delhi gang rape and a significant increase in rape reporting in the 39 months afterwards.[37] The increase is confirmed by interviews with reporters who said it has become far easier to have articles on rape commissioned after December 2012.[38]

It is worth noting that a second significant spike is seen during August 15 to September 15, 2013, which coincides with the widely-covered August 2013 gang-rape case in Shakti Mills in Mumbai,[39] suggesting that the largest spikes in coverage could be correlated with cases in the bigger metropolises.

Another noteworthy observation is the small but steady increase in rape-related keywords already beginning to appear prior to the Delhi gang rape, suggesting that this spike in coverage in December 2012 could have been, in part, precipitated by an already increasing awareness and interest in the topic.

Figure 1: Number of times the terms “rape” or “gang rape” appear in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

Reporters working on rape cases attribute this awareness to a rise in the number of women entering India’s urban workforce over the past two decades.[40] Even though female participation in India’s labor force remains low at around 27 percent,[41] employment opportunities for educated, English-speaking, city-based women have increased since the mid-1990s, particularly call center and business processing work which often includes evening and night shifts. This has coincided with the ongoing trend of economic migration from rural to urban areas,[42] which in turn has raised concerns among India’s city-dwelling middle classes over the large number of poor, uneducated, young male migrants who now live in urban areas without the social constraints of their family or village and who are perceived to be a threat to law and order.[43]

A look back at some of the widely reported cases of sexual violence prior to the December 2012 rape shows that the English-language press was becoming increasingly preoccupied with the issue of safety for middle-class working women in public spaces. An example of this is the 2010 Duala Kuan gang rape case in which a female employee of an outsourcing office in Delhi was abducted and gang raped by a group of men after a night shift. After reporting the details of the case and the prosecution of the suspects, newspapers turned their focus toward initiatives to protect women traveling home from work late at night.[44] But despite this focus, reporters working on sexual violence before December 2012 said it was considered a fringe issue. “Many people saw this as a new wave of feminism, which was partially true and not true,” said former Tehelka magazine journalist, Revati Laul. She recalled being told by an editor to write up her work as a side feature, rather than a main news story. “I had a huge fight with him over that. He said gender was a features issue and not political,” she said.[45]

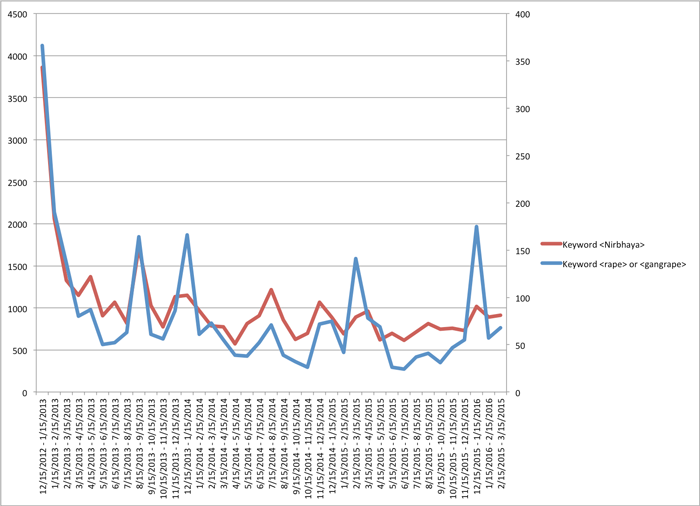

A deeper look at the data sheds further light on whether the increase in rape reporting was specific to the December 2012 case, or was more general in nature. A keyword search on the term <Nirbhaya> in the same months and same newspapers as above (however, note the different scale on the right) showed that it spiked in tandem with general rape coverage (scale on the left), as well on anniversaries of the incident, and on significant events related to the case, like court hearings and the March 2015 release of the BBC documentary on the December rape, “India’s Daughter,” which included a controversial interview with one of the convicted attackers.[46] But what is also clear from this graph is that general rape coverage persisted in the absence of Nirbhaya-specific coverage, at a rate higher than was previously the case.

Figure 2: Number of times the term “Nirbhaya” vs. terms “rape” or “gang rape” appear in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

Why Jyoti Singh?

Interviews with editors and journalists who covered the December 2012 rape case have identified three key reasons as to why it became a trigger event: the victim was perceived to be from the right class, she was perceived to have been blameless for the crime, and she was raped by strangers.

“People Like Us”

India’s English-language media houses tend to be staffed by upper class and upper caste workers.[47] It’s widely believed that for a crime to have resonance with the staff and the readership of the paper, the victim or the perpetrator must also match this status.

India’s English-language media houses tend to be staffed by upper class and upper caste workers. It’s widely believed that for a crime to have resonance with the staff and the readership of the paper, the victim or the perpetrator must also match this status.

“There is this term we use called PLU – it means ‘people like us,’” said former Times of India reporter Smriti Singh, who was covering legal affairs when the story broke. “Whenever there is a murder or rape case involving a female, in your head you have a checklist as to whether the story qualifies to be reported or not. You have to think whether the victim is a PLU,” she said.[48] In essence, this means someone who is from India’s upper or middle classes, who can speak English, who goes out and has a social life, and who might be working.

Victims who do not fit this profile tend to generate little coverage. Singh described a rape case that happened before December 2012 in which an 80-year-old homeless woman was raped by a Delhi rickshaw puller. “Her injuries were similar to this case,” said Singh. “The story went on page 6 or 7, single column, somewhere at the bottom. So I tried explaining to my editor that the injuries had been really grave and the order (court documents) had been terrifying to read. But nobody cared because it was a homeless female and the accused was a rickshaw-puller,” she said.

The fact that English-language newsrooms tend to display an editorial bias towards covering urban PLU cases means many rapes in India go unreported. “There is a vast country beyond Delhi and Mumbai and there is a lot of crime happening there and those people are in need of exposure and a platform,” said Priyanka Dubey, a reporter who describes herself as small-town, lower-middle-class Hindi journalist who has struggled to have stories on sexual violence published in the English media.[49] Underlying this is the understanding that focusing on poverty does not sell papers.[50] “I was wary of why the Jyoti Singh story captured the Indian imagination,” said Aditi Saxton who was working at the news magazine Tehelka when the story broke.[51] Saxton said her editorial team had researched horrific stories of sexual violence in other parts of the country, but felt these would fail to capture the imagination of their affluent readership like the December 2012 case did. “It fed very much into the ‘people like us’ narrative because of the decision she took to go to a movie and take a bus home – all of these decisions are familiar to women belonging to a certain socio-economic class,” she said.

In fact, Jyoti Singh was not a PLU. As details emerged of her family background, it became clear she was not from the established middle class, but was aspiring to transcend her working class roots. Jyoti was initially described as a medical student, which would have placed her in the context of money and connections. But, in fact, she was studying to become a physiotherapist. Her father was a laborer at Delhi airport who had saved up to put his daughter through college. “She was actually from the PLT (“people like them”) side,” said former Times of India editor Manoj Mitta. “But people didn’t realize that because she happened to come out of a mall in South Delhi which was frequented by middle class people.”[52] But by the time editors realized Jyoti’s profile did not match their readership, the story was unstoppable.

A Blameless Victim

Unlike previous rape victims, whose conduct had been questioned in the Indian media, Jyoti Singh largely avoided being seen as responsible for her own rape. Because of this, she became a victim who could be celebrated as a heroine – a “Braveheart” – without judgement.

Reporters who cover sexual violence say a pervasive attitude of victim blaming, which has implications of consent, often underpins Indian rape coverage.

“I don’t think newspapers indulged in victim blaming in this particular case. They didn’t say, what was she doing at that late hour?” said former editor Manoj Mitta.[53] English-language newspapers did report the inflammatory remarks of some male lawmakers and public figures who suggested Jyoti Singh invited the rape by being out at night with a boyfriend and should bear some of the guilt. For instance, the influential Hindu guru, Asaram Bapu, argued that if Jyoti had addressed her attackers as brothers, they would have relented.[54] The guru’s words were generally condemned by correspondents, who described the religious leader as adding to the shame of the situation or suffering from “foot-in-the-mouth tendencies.”[55] “I remember that was something reported at the time – not necessarily approvingly by the media. They just reported it as one more controversial angle to the case,” said Mitta.

Reporters who cover sexual violence say a pervasive attitude of victim blaming, which has implications of consent, often underpins Indian rape coverage. “If someone comes and claims they have been raped, then the first question is, what did this girl do wrong?” said former Times of India reporter Smriti Singh.[56] An example of this is the 2014 Delhi Uber taxi driver rape case, in which it was widely reported that the victim fell asleep in the back of the car.[57] “[The media] talks about personal behavior but it’s done in a very objective manner. But there is an underlying thought to it. It’s always brought up too much when a girl lapses in her security,” said Hindustan Times reporter Avantika Mehta.[58]

Stranger Rape

One of the key reasons Jyoti Singh’s case caught the public imagination was because she was raped by strangers. Her attack confirms the universally popular, horror-story narrative that the biggest danger for a woman comes from leaving her home and social circle and entering a world of unknown men. This narrative persists in India, despite National Crime Record Bureau figures that consistently show that around 90 percent of rapes are committed by perpetrators known to the victim, such as partners, family members, neighbors and work colleagues.[59]

An article in The Hindu from 2014 compares NCRB figures with figures from the National Family Health Survey and concludes that “just 2.3 percent of rape was by men other than the husband.”[60] Yet the rapes that gain the most coverage in the English-language press are rapes, often brutal gang-rapes, committed by strangers. In her 2003 article “News Portrayals of Violence and Women: Implications for Public Policy,” Elizabeth Carll argues that by presenting stories of violence against women as separate isolated events, the news media “denies the social roots of violence against women and absolves the larger society of any obligation to end it.”[61]

Freelance journalist Neha Dixit, who specializes in writing about sexual violence, agrees that the media’s focus on horrific, stranger-rape cases means the issues behind attacks do not need to be addressed. “Statistics show most cases happen in the home, school, work environment and we have a very high incidence of incest in this country, but nobody wants to talk about it because nobody wants to question the family and patriarchal structure,” she said.[62]

Characteristics of the Coverage

The Gory Details

A marked characteristic of the December 2012 rape reporting in India’s English-language press was its focus on explicit and sensational details. Jyoti Singh was gang raped and sodomized by six men who also raped her with an iron rod. During the attack, they pulled out her intestines which they threw out of the bus. The sensational aspects of the case quickly dominated coverage. In some cases, journalists took information from leaked police reports and used this as the basis for highly imaginative reporting, such as in this story from the weekly English-language magazine, India Today, which is written from the perspective of one of the rapists. “The high point of his life was when he thrust his tightly clenched right fist into the womb of the bruised and battered 23-year-old on the night of December 16. Nothing beat the excitement he felt when he heard her muzzled screams, saw her writhe in extreme pain and watched the blood spurting from her young body.”[63]

Reporters covering the December 2012 rape knew that publishing sensational details would boost sales. “The story was inherently sensational and the coverage was driven by the conviction that people were very curious to know about it and there was competition with other newspapers,” said former Times of India editor, Manoj Mitta.[64] “India’s media sector is at a crossroads. It’s trying to act like the foreign media but it’s still competing to get the news first and to get more details,” said ex-Times reporter Smriti Singh.[65]

Many reporters say they found this focus on the explicit details of the rape unpalatable. One journalist who worked closely with the victim’s family said they were uncomfortable with the coverage, especially directly after the attack when they thought their daughter might live to witness it.[66] Others accept, with reluctance, the demands of their job. “I have real qualms on reporting on rape…but I provide the details if the editors want them. I try not to fight too much with my editors,” said Hindustan Times reporter Avantika Mehta. “Until there are definite guidelines for journalists that are properly issued by the Press Club of India, I don’t think we’ll be able to stop putting in those details.”[67] Generally the inclusion of sensational information is seen as an unavoidable trend. “All our reporting has become more tabloid across the board. So we’ve become voyeurs who are like T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men – with heads full of straw,” said former Tehelka writer Revati Laul.[68]

A Crime of Passion

A characteristic of the sensational coverage of the December 2012 rape was how it was portrayed as a crime of lust, rather than one of aggression. Longstanding rape myths include the notion that rape is sex, that the assailant is motivated by lust, that men have a natural predisposition to get sex through force, and that women provoke rape through their looks and behavior.[69] Again, many reporters are uncomfortable with this aspect of the coverage. “The emphasis is now on male behavior which is lustful….But this is not desire or lust. It’s a violent crime,” said reporter Avantika Mehta. “You don’t say that about a serial killer – that he lustily put in his knife,” she said.[70]

A characteristic of the sensational coverage of the December 2012 rape was how it was portrayed as a crime of lust, rather than one of aggression.

Freelance reporter Neha Dixit sees the focus on sexual gratification as another attempt to divert attention to the real issues behind sexual violence. “Everybody thinks in most cases the man is trying to satiate his sexual appetite. But that’s not the case. There is class hierarchy, caste hierarchy, sectarian violence – and there is this notion of honor which is why people from one community rape the other community thinking that is how they’ll be able to establish their supremacy over the other. So there are all these patriarchal notions that need to be questioned but nobody wants to do that,” she said.[71]

The pictures used to illustrate rape stories can also contribute to the framing of the crime as one motivated by lust. In India’s English-language print media there is a tendency to publish illustrations of scantily-clad girls cowering as the hands or shadows of men loom over them. This type of cartoon was used repeatedly in many publications throughout the December 2012 coverage,[72] raising questions about whether newspapers are deliberately sensationalizing the crime by focusing attention onto the humiliation of the victim.[73] “To my mind this says something important as to why these stories get the space they do – which is, they’re seen almost as a kind of slight eroticism,” said Praveen Swami, the former Hindu, now Indian Express, editor.[74]

The Crime Beat

It is worth adding a few comments on where rape stories are placed within India’s English-language publications. Within daily newspapers, sexual violence is primarily covered by the crime and court reporters, which means it is sourced from police reports and restricted to the word length of a news story (200-500 words) in the news pages. Even after the December 2012 rape, it is rarely covered as a social issue and given prime billing in the social or political pages. “Sexual violence is largely covered by crime reporters who do their stories along with every other crime,” said editor Praveen Swami. “So the most they are going to give it is 3 paragraphs on page 11 along with 2 murders and a traffic accident.

There are some journalists who have done excellent work on issues connected with gender, but themes to do with women’s issues haven’t really emerged as part of a newspaper’s menu of narrative,” he said.[75]

The exception to this is long-form magazines like Tehelka and Caravan, which have devoted pages to examining the social issues behind rape. But even here, there is a sense that more could be done. “With sexual violence, specific incidents that are specifically gruesome do get highlighted, but the background, the persistent background of sexual violence over a period of time, that does not get the attention that it merits,” said Caravan editor Hartosh Singh Bal. “It’s difficult to report that kind of story in a way that is compelling,” he said. “People get sort of inured.”[76]

A number of reporters say the problem with reporting sexual violence only as a crime story, rather than also examining it as a continuing social issue, is that editors are continually on the lookout for sensational stories that could provoke the same audience reaction as the December 2012 rape. Certain trigger words, such as “juvenile,” “gang-rape,” and “brutality” now guarantee space in the paper. “It’s a catchphrase,” said reporter Avantika Mehta. “Everyone is thinking if it’s a rape case, they’ll file because you never know. But to me that’s insensitive reporting as that’s not news. Not every rape case should make the news.”[77]

The Effect on Public Policy

The Verma Committee

The Indian government’s immediate reaction to the angry public protests that followed the December 2012 rape was to set up a legal committee to look into the country’s laws and attitudes towards women.[78] Led by retired Justice J.S. Verma, retired Justice Leila Seth and Solicitor General Gopal Subramanium, the committee received thousands of submissions from civil society, feminist organizations and legal institutions from both within India and abroad. The 600-page report is wide-reaching and visionary, and deals not only with recommended changes to India’s colonial-era sexual violence legislation, but also questions the country’s traditional patriarchal society and its often brutal and callous treatment of women. The report examines gender equality and justice, the trafficking of women and girls, sexual harassment in the workplace, child sexual assault, honor killings, the forensic examination of sexual assault victims, police reform, and education. It opens with a quote from the Indian independence leader, Mahatma Gandhi, on how India’s patriarchal mindset holds society back: “By sheer force of a vicious custom, even the most ignorant and worthless men have been enjoying a superiority over woman which they do not deserve and ought not to have. Many of our movements stop half way because of the condition of our women.”[79]

Others felt the Verma Committee report could have been the basis for a larger series of stories… thus placing sexual violence reporting within a larger framework….In doing so, reporters would inevitably question India’s dominant patriarchal mindset. However, editors say there is a general reluctance to do this.

The Verma Committee released their findings at a press conference which was broadcast live to the nation. English-language newspapers quickly published stories online complete with links to the report and its proposed criminal law amendments, with many also providing a list of key takeaways. Although certain aspects, such as the recommendations not to lower the age of criminal responsibility for juveniles and not to introduce the death penalty for rape, were widely discussed in the press, former Times of India editor, Manoj Mitta, argues that most of the report’s findings were glossed over. “There is a 600-page report dealing with all sorts of intricacies and they [newspapers] focused on recommendations, the operational part….But in the process, other details which may be important but were not as compelling did not get that much attention,” he said.[80]

Some editors found the long and often technical report too theoretical and out of touch with Indian reality. “It was clear to me that none of this was going to happen,” said Praveen Swami. “There was a vague statement that we must improve forensics but absolutely no mention of how this was going to be done….So where on earth were these resources to come from? In my view the things that were talked about seemed fairly tokenistic,” he said.[81]

But others felt the Verma Committee report could have been the basis for a larger series of stories examining all the issues it considered, thus placing sexual violence reporting within a larger framework. “The same sort of issues that had already been highlighted in the cases earlier were the ones picked out and reported on. I think what we need is persistent attention,” said Caravan editor Hartosh Singh Bal.[82] In doing so, reporters would inevitably question India’s dominant patriarchal mindset. However, editors say there is a general reluctance to do this. “I think this is the problem with mass circulation newspapers – they are very often loath to annoy their audiences, at least in any profound way,” said Praveen Swami. “And having a conversation about Indian society’s attitude to women, the role of women, and what their rights constitute would be pushing, in my view, too far,” he said.[83] Editor Singh Bal agrees that the issue is generally sidestepped. “The question of family structure, of social inhibitions in terms of reportage, how shame operates, how patriarchy cooperates within family systems to make sure these crimes are suppressed – these issues don’t get told in a sustained manner,” he said.[84]

In answering the question why India’s patriarchal society is not questioned more thoroughly by the press, reporters and editors also point to the patriarchal bias within newsrooms themselves. “I realized I had my own bias and it had come from years of listening to men say things like ‘how can you convict him, he’s innocent until proved guilty and it’s his word against hers and his word is much more important than hers.’ It’s something you grow up with here and it’s something you internalize quite easily,” said Hindustan Times reporter, Avantika Mehta.[85] “I think many reporters share the biases of society – exactly like many police officers. And rape still isn’t something society takes very seriously,” said Praveen Swami.[86]

Newspaper Campaigns

A number of English-language publications used the December 16 rape as an opportunity to pursue their own campaigns to change India’s laws. One of the more notable campaigns was run by The Times of India to lower the age of criminal responsibility. This followed a widely circulated report, sourced from the police, that the juvenile suspect in the December 16 rape had been the most brutal of the perpetrators. “Suddenly out of the blue, one report came in one newspaper which said the police had claimed the juvenile was the most brutal of the accused…. So it was a gospel truth. No one questioned it, how it came about, whether the police had said it or not, whether it was the reporter’s figment of their imagination,” said Smriti Singh, who was following the story as a legal reporter for the Times.[87]

But subsequent information from the juvenile suspect’s trial showed that, in fact, there was no evidence that he had been the most brutal of the attackers.[88] When reporters and editors at The Times of India tried to publish this, they faced opposition from senior management. “I went to my editor and he rejected the story, so I went to another editor who said he would run the story with me and it took us about a week and a half to get the story printed in the newspaper,” said Singh. “But the way it was placed, it went unnoticed. We did finally manage to write the story, but the headline went as a question mark. “The juvenile is not the most brutal of them all?” So they diluted the story in the process,” she said.

This frustration was not only felt at the reporting level. “A senior person like me who had decades of experience and standing as someone who deals with legal and human rights issues, even somebody like me was gagged by my editors,” said ex-Times of India editor, Manoj Mitta, who also tried to publish a story correcting the earlier reports. “They said ‘if you feel so strongly about it, write it as a blog. We’re not going to let it be printed in the newspaper.’…They said ‘we have taken an editorial stand on the subject. We can’t afford to confuse our readers.’ They had the view that increasingly, juveniles are committing their heinous offences.”[89]

In 2015, against the advice of the Verma Committee, the Indian government amended the juvenile justice law to lower the age of criminal responsibility from 18 to 16 in the case of “heinous crimes” like rape or murder. [90] The Times of India celebrated the success of their campaign with the headline: “Now, 16-18-yr-olds won’t get off lightly for serious crimes.”[91] But Indian Express editor Praveen Swami is skeptical about how much influence the Times actually had on government policy, arguing that the campaign fit with a pre-existing belief about mass urban migration: that young men are becoming lawless and out of control. “One of the great vanities is that what we write actually shapes public or political discourse, but the fact is, successive governments don’t really give a toss about what was said on a whole host of issues,” he said.[92]

It’s worth mentioning here the English-language publications’ coverage of marital rape following the December 2012 attack. Under the section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, rape within marriage is not seen as a crime unless the wife is under the age of 15.[93] Immediately after the rape, a number of publications, led by the magazine Tehelka, took up the cause enthusiastically[94] and there was widespread coverage of the Verma Committee’s recommendation that marital rape should be criminalized.[95]

But in this case, press attention seemed to have had little effect. In March 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government announced that they would not criminalize marital rape because of cultural and societal factors within Indian society, with the Indian Home Minister, Maneka Gandhi, asserting it was the Indian “mindset of society to treat the marriage as a sacrament.”[96] Although the English-language press has subsequently printed opinion pieces by feminists and civil society actors protesting this decision, newspapers appear to have had little influence on this issue.

A Backlash to the Reporting?

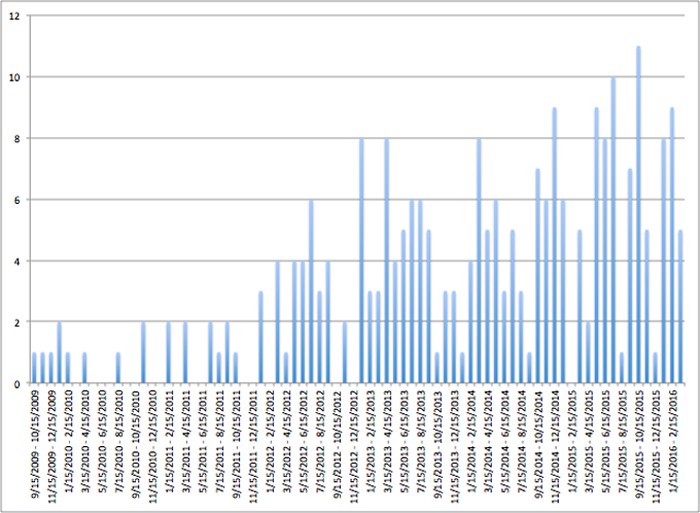

In 2014, India’s English-language newspapers covered data from the Delhi Commission of Women showing that 53 percent of rape cases filed in the city in the previous year were false.[97] In this instance, a case was defined as false if the victim withdrew their rape claim before or during prosecution. The study data did not include the reasons why cases were withdrawn, or whether the victim was under any pressure to do so. A data analysis of the term <false rape> in the four English-language newspapers analyzed shows a small but significant rise in reports on this issue from 2012.

Figure 3: Number of times the term “false rape” appears in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

Press articles attribute the rise in the number of false rape cases after December 2012 to the government’s amendments to sexual violence legislation, which are believed to have made it easier for women to falsely allege they have been raped.[98] Some coverage also reflects an established Indian narrative that women are prone to file false cases when they have been caught having a sexual relationship outside marriage, let down after a promise of marriage, pursuing a personal vendetta or trying to extort money.[99]

However, a recent data survey conducted by Avantika Mehta from The Hindustan Times puts the level of false rape complaints at a much lower 13-14 percent, though she said a portion of this figure is taken from the number of victims who later marry the perpetrator and it does not necessarily prove that the rape claim was false.[100] Both reporters and editors say more work is needed on this issue to discover the truth behind the statistics, which are generally reproduced on news pages as straight news without analysis.[101]

Conclusion and Recommendations

The December 16, 2012 rape was an unprecedented trigger event that brought the issue of sexual violence onto India’s front pages. The huge public interest in the story both increased press coverage of sexual violence in India, as well as highlighted the challenges that exist within that coverage, and its subsequent effect on public opinion and policy. Based on the experiences of editors and journalists working within this field, this paper makes a number of recommendations to the actors involved.

Government

The Congress Party-led Indian government responded to the December 2012 by establishing the Verma Committee and amending the criminal law, a move that gained cross-party parliamentary support.[102] However, despite its commitment to improving the status of female children in India,[103] the subsequent government of the Bharatiya Janata Party, led by Narendra Modi, has rejected the advice of the Verma Committee by lowering the age of juvenile criminal responsibility and by not criminalizing marital rape. This paper urges the BJP government to continue to refer to and be guided by the Verma Committee report which stands as a comprehensive examination of the status of women in India and provides considerable advice on how to tackle the issue of sexual violence.

Regulatory Bodies

From a regulatory standpoint, this paper urges stronger and more rigorously enforced regulation by the Press Council of India. Not only should the council be given the authority to fine publications if they violate section 228A of the Indian Penal Code, it should also be authorized to hold them accountable for reporting that is unnecessarily sensational, graphic and distressing to the victim or their family. An industry-wide code concerning how sexual violence should be reported could be drawn up by the Press Council and used as a basis for training new reporters. Media-watch websites, such as The Hoot, which already give guidance to reporters, could be further used to spark discussion and debate around the coverage of sexual violence and help raise journalists’ awareness of the negative effects of sensational and victim blaming reporting.

Newspaper Editors and Journalists

India’s English-language newspapers are commercial businesses, and this paper recognizes that attracting and catering to an audience is an essential part of this business. But it is important to draw a distinction between covering sexual violence and sensationalizing it to sell newspapers, especially as new research from Harvard has found evidence that “biased news coverage of rape – which blames the victim, empathizes with perpetrators, implies consent, and questions victims’ credibility – may deter victims from coming forward, and ultimately increases the incidence of rape.”[104] India’s English-language newspapers can improve their coverage of sexual violence by following these recommendations:

- Reporters and editors should be trained to report with greater sensitivity toward victims of sexual violence and to avoid over-sensationalizing rape cases in a ploy to increase sales.

- Rape should not be defined as a lust crime, and should not be illustrated by pictures of distressed, scantily-clad women.

- More consideration should be given to non-PLU cases, such as rape in rural areas, rape within the home and rape in conflict areas.

- Sexual violence should not only be reported in the crime pages, but should be examined in depth as a gender issue in the social, economic and political pages of the paper.

- Newsrooms should appoint specially-focused gender reporters to ensure rape is not covered as a one-off event, but is reported within the social context that it occurs.

- Finally, with research showing that female journalists are much more likely to focus on women’s issues than their male colleagues,[105] more women should be employed by publications – both as reporters and in senior positions, to ensure that women’s issues play a more central role in coverage as a whole.

All the journalists interviewed for this paper have said that since the December 2012 rape, it has become far easier to publish articles about sexual violence. But, like reporter Priyanka Dubey, they question whether publications are doing the most they can to fully examine and explain this troubling social phenomenon. “There has been so much noise about sexual violence that it’s become compulsory for papers to publish stories out of pressure,” said Dubey. “The 2012 protests created that environment, but the coverage has to come from the heart and newsrooms and editors need to understand that this can’t go on.”[106]

Acknowledgements

This paper could not have been written without the assistance of Uzra Khan, my research assistant and a Master’s candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School, who worked with me throughout my spring fellowship at the Shorenstein Center. Her data gathering and analysis skills were invaluable, as was her intelligence, tenacity and friendship. I also wish to thank Tom Patterson for his brilliant leadership and edits, and Nancy Palmer, Katie Miles, Nilagia McCoy and other staff members for their many kindnesses throughout the program. Thanks to Matthew Baum and Dara Cohen for sharing their ground-breaking research on rape culture in the U.S., and to Tim Bailey for helping Dara and I lecture together on this subject. I’m indebted to Professor Michael Ignatieff for his interest and encouragement in this often overlooked topic. Finally, a very special thanks to fellows Johanna Dunaway, Dan Kennedy, and Marilyn Thompson who not only provided great support, but also much fun during the semester.

Endnotes

[1] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[2] Daniel Drache and Jennifer Velagic, “A Report on Sexual Violence Journalism in Four Leading Indian English Language Publications Before and After the Delhi Bus Rape,” York University, June 10, 2013. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2277310

[3] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[4] Sanjoy Majumder “Delhi Bus Gang Rape: Protests and Vigils across India,” BBC News, December 18, 2012. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-20774611

[5] Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen, An Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 109.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Elizabeth K. Carll, “News Portrayal of Violence and Women: Implications for Public Policy.” American Behavioral Scientist 46.12 (2003): 1601. http://abs.sagepub.com/content/46/12/1601.abstract

[8] Reetinder Kaur, “Representation of Crime against Women in Print Media: A Case Study of Delhi Gang Rape,” Anthropology 02, No. 1 (2013): 3.

[9] Uzra Khan, “Indian Media: Crisis in the Fourth Estate,” Kennedy School Review, August 18, 2015. http://harvardkennedyschoolreview.com/indian-media-crisis-in-the-fourth-estate/

[10] 2014 Nielsen Indian Readership Survey. http://mruc.net/sites/default/files/IRS%202014%20Topline%20Findings_0.pdf

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Daniel Drache and Jennifer Velagic, “A Report on Sexual Violence Journalism in Four Leading Indian English Language Publications Before and After the Delhi Bus Rape,” York University, June 10, 2013. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2277310

[16] 2014 Nielsen Indian Readership Survey. http://mruc.net/sites/default/files/IRS%202014%20Topline%20Findings_0.pdf

[17] Ibid.

[18] Manu Balachandran, “How Tehelka Is Attempting to Remake Itself after Tarun Tejpal,” Quartz, December 30, 2014. http://qz.com/318917/how-tehelka-is-attempting-to-remake-itself-after-tarun-tejpal/

[19] Sruthi Gottipati, “The Caravan,” The New York Review of Magazines, 2010. http://nyrm.org/?page_id=516

[20] Uzra Khan, “Indian Media: Crisis in the Fourth Estate.” Kennedy School Review, August 18, 2015. http://harvardkennedyschoolreview.com/indian-media-crisis-in-the-fourth-estate/

[21] Anuradha Sharma, “In Need of a Leveson? Journalism in India in Times of Paid News and ‘Private Treaties,’” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2013, 9, 14. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/In%20need%20of%20a%20Leveson-%20Journalism%20in%20India%20in%20times%20of%20paid%20news%20and%20private%20treaties.pdf

[22] Ken Auletta, “Citizens Jain,” The New Yorker, October 8, 2012. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/10/08/citizens-jain

[23] John Lloyd, “A Week inside India’s Media Boom,” The Financial Times, October 19, 2012. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/0eb44760-1907-11e2-af88-00144feabdc0.html

[24] Ken Auletta, “Citizens Jain,” The New Yorker, October 8, 2012. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/10/08/citizens-jain

[25] Hartosh Singh Bal interview via Skype with author, March 14, 2016.

[26] Section 228A in the Indian Penal Code. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1696350/

[27] Anuradha Sharma, “In Need of a Leveson? Journalism in India in Times of Paid News and ‘Private Treaties,’” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2013, 48. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/In%20need%20of%20a%20Leveson-%20Journalism%20in%20India%20in%20times%20of%20paid%20news%20and%20private%20treaties.pdf

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Reporting Rape,” The Hoot, September 26, 2013. http://www.thehoot.org/resources/reporting-rape

[30] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[31] Shakuntala Rao, “Covering Rape in Shame Culture: Studying Journalism Ethics in India’s New Television News Media,” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 29.3, (2014), 156-7.

[32] Praveen Swami interview via phone with author, March 28, 2016.

[33] Interview with employee from The Indian Express via phone, March 17, 2016.

[34] “My Daughter’s Name Was Jyoti Singh. Not Ashamed to Name Her: Nirbhaya’s Mother,” The Times of India,” December 18, 2015. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/My-daughters-name-was-Jyoti-Singh-Not-ashamed-to-name-her-Nirbhayas-mother/articleshow/50206977.cms

[35] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 17, 2016.

[36] “BREAKING: SC Again Violates Privacy of a Rape Victim; Mentions Her Name and Age – Ironically, Voices Concern over Violence against Women! [Read the Judgment],” Live Law,” February 18, 2015. http://www.livelaw.in/breaking-sc-violates-privacy-rape-victim-mentions-name-age-ironically-voices-concern-violence-women/

[37] The average number of results for the key word search in the 39 months prior to the Delhi gang rape is 261.92 per month, while in the 39 months after the Delhi gang rape it is 1015.87 results per month – close to four times the number of hits overall on average. While it is clear that rape-related keywords do not provide an absolute and accurate measure of the increase in rape coverage in the aftermath of the Delhi gang rape, the difference in means before and after, statistically significant at a confidence level of 99.9%, do provide an illuminating picture of the coverage that complements the personal anecdotes of editors working at these newspapers at the time.

[38] Neha Dixit interview via Skype with author, March 8, 2016. Interview with employee from The Indian Express via phone, March 17, 2016. Priyanka Dubey interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016.

[39] “They Threatened to Kill Me with a Beer Bottle: Mumbai Gangrape Victim Recounts the Horror,” India Today Online, August 24, 2013. http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/mumbai-gangrape-victim-shakti-mills-compound-22-year-old-photojournalist/1/301192.html

[40] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[41] World Bank 2014 figures, “Labor Force Participation Rate, Female (% of Female Population Ages 15 ) (modeled ILO Estimate).” http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS

[42] Rameez Abbas and Divya Varma, “Internal Labor Migration in India Raises Integration Challenges for Migrants,” Migrationpolicy.org, March 3, 2014. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/internal-labor-migration-india-raises-integration-challenges-migrants

[43] Praveen Swami interview via phone with author, March 28, 2016.

[44] Sanjeev Ahuja, “BPOs, Cops Join Hands to Ensure Safety of Women,” Hindustan Times, November 29, 2010, http://www.hindustantimes.com/india/bpos-cops-join-hands-to-ensure-safety-of-women/story-2UKWMeG0gkJ23DxwHaDkpK.html

[45] Revati Laul interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[46] “BBC Four’s Storyville to Broadcast Interview with Convicted Delhi Gang Rapist Mukesh Singh,” BBC, March 04, 2015. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2015/storyville-indias-daughter

[47] Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen, An Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 107.

[48] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[49] Priyanka Dubey interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016.

[50] Ken Auletta, “Citizens Jain,” The New Yorker, October 8, 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2015/storyville-indias-daughter

[51] Aditi Saxton interview via Skype with author, March 18, 2016.

[52] Manoj Mitta interview via phone with author, March 17, 2016.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Frank Jack Daniels, and Satarupa Bhattacharya. “Asaram Bapu’s View on Delhi Rape Raises Anger, but Shared by Many,” Reuters India, January 7, 2013. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-rape-views-idUSBRE9080JL20130109

[55] “Asaram Bapu Adds to Shame, Says Victim at Fault Too,” Hindustan Times, September 8, 2013. http://www.hindustantimes.com/india/asaram-bapu-adds-to-shame-says-victim-at-fault-too/story-MRHCt4yF8GFQZLpgj8UReK.html

“Delhi Gang-rape Incident: Asaram Blames Nirbhaya, Sparks Furore,” The Times of India, January 8, 2013. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Delhi-gang-rape-incident-Asaram-blames-Nirbhaya-sparks-furore/articleshow/17933863.cms

[56] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[57] Sameera Khan and Shilpa Phadke, “Why It Is Totally Wrong to Attack the Uber Victim for Falling Asleep in the Cab,” Quartz, December 14, 2014.

[58] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[59] In 2014, 86 percent of perpetrators were known to their victims, according to India’s National Crime Records Bureau. http://ncrb.nic.in/

[60] Rukhmin S., “Marital and Other Rapes Grossly Under-Reported,” The Hindu, October 22, 2014. http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/marital-and-other-rapes-grossly-underreported/article6524794.ece

[61] Elizabeth K. Carll, “News Portrayal of Violence and Women: Implications for Public Policy,” American Behavioral Scientist 46.12 (2003): 1603. http://abs.sagepub.com/content/46/12/1601.abstract

[62] Neha Dixit interview via Skype with author, March 8, 2016.

[63] Bhuvan Bagga, “The Unforgiven,” India Today, December 28, 2012. http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/crimes-of-six-accused-in-delhi-gangrape-case/1/239847.html

[64] Manoj Mitta interview via phone with author, March 17, 2016.

[65] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[66] Interview with employee from The Indian Express via phone, March 17, 2016.

[67] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[68] Revati Laul interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[69] Daniel Drache and Jennifer Velagic. “A Report on Sexual Violence Journalism in Four Leading Indian English Language Publications Before and After the Delhi Bus Rape,” York University, June 10, 2013, 18.

[70] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[71] Neha Dixit interview via Skype with author, March 8, 2016.

[72] “City of Shame: Three Minors Raped in 48 Hours in Delhi,” Hindustan Times, March 27, 2016. http://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/three-minors-raped-in-48-hours/story-5mqETlBH3UA6a97dUPy8yI.html “Girl Gang-raped in Moving Bus in Delhi,” The Times of India, December 17, 2012.

[73] Shakuntala Rao, “Covering Rape in Shame Culture: Studying Journalism Ethics in India’s New Television News Media,” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 29.3, (2014), 163. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08900523.2014.918497

[74] Praveen Swami interview via phone with author, March 28, 2016.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Hartosh Singh Bal interview via Skype with author, March 14, 2016.

[77] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[78] J.S. Verma, Leila Seth, and Gopal Subramaniam. “Report of the Committee on Amendments to Criminal Law,” January 23, 2013. http://www.thehindu.com/news/resources/full-text-of-justice-vermas-report-pdf/article4339457.ece

[79] Ibid.

[80] Manoj Mitta interview via phone with author, March 17, 2016.

[81] Praveen Swami interview via phone with author, March 28, 2016.

[82] Hartosh Singh Bal interview via Skype with author, March 14, 2016.

[83] Praveen Swami interview via phone with author, March 28, 2016.

[84] Hartosh Singh Bal interview via Skype with author, March 14, 2016.

[85] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[86] Praveen Swami interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016.

[87] Smriti Singh interview via Skype with author, March 9, 2016.

[88] Smriti Singh & Manoj Mitta. “Nirbhaya Case Juvenile Wasn’t ‘most Brutal’?” Times of India, October 3, 2013. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Nirbhaya-case-juvenile-wasnt-most-brutal/articleshow/23426346.cms

[89] Manoj Mitta interview via phone with author, March 17, 2016.

[90] “Juvenile Justice Bill Passed in Rajya Sabha,” The Hindu, December 23, 2015. http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/juvenile-justice-bill-passed-in-rajya-sabha/article8018448.ece

[91] Mayank Jain, “Wait Is Over: How the Media Reported the Juvenile Justice Bill Being Cleared by Rajya Sabha,” Scroll.in., December 23, 2015. http://scroll.in/article/777582/wait-is-over-how-the-media-reported-the-juvenile-justice-bill-being-cleared-by-rajya-sabha

[92] Praveen Swami interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016.

[93] Kanika Sharma and Aashish Gupta, “When Even Rape Is Legal,” The Hindu, June 18, 2015. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/when-even-rape-is-legal/article7298898.ece

[94] “Marital Rape Not a Crime, Can’t Alter Constitution for Individual Cases: Supreme Court,” Tehelka, July 1, 2015. http://www.tehelka.com/2015/07/marital-rape-not-a-crime-cant-alter-constitution-for-individual-cases-supreme-court/

[95] “Wanted: A Verma Ordinance,” The Hindu, February 4, 2013. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/editorial/wanted-a-verma-ordinance/article4375579.ece

[96] Shuma Raha, “Marital Rape: Why Maneka Gandhi Has Got It Horribly Wrong,” The Times of India, March 12, 2016. http://blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/random-harvest/marital-rape-why-maneka-gandhi-has-got-it-horribly-wrong-2/

[97] “53% Rape Cases Filed between April 2013 and July 2013 False: Delhi Commission of Women,” DNA India, October 4, 2014. http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-53-rape-cases-filed-between-april-2013-and-july-2013-false-delhi-commission-of-women-2023334

[98] Sana Shakil, “Tougher Rape Law Leading to Increase in False Cases,” The Times of India, February 22, 2014. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Tougher-rape-law-leading-to-increase-in-false-cases/articleshow/30807940.cms

[99] Joanna Jolly, BBC documentary “Resisting Rape,” December 5, 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/proginfo/2013/49/r4-thurs-crossing-continents-india-resisting-rape

[100] Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[101] Praveen Swami interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016, Avantika Mehta interview via Skype with author, March 16, 2016.

[102] “New Anti-Rape Law Comes into Force,” The Times of India, April 3, 2013. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/New-anti-rape-law-comes-into-force/articleshow/19359543.cms

[103] Himanshi Dhawan, “PM Modi Launches ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ Campaign, Says Female Foeticide Is a Sign of ‘Mental Illness,’” The Times of India, January 23, 2015. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/PM-Modi-launches-Beti-Bachao-Beti-Padhao-campaign-says-female-foeticide-is-a-sign-of-mental-illness/articleshow/45985741.cms

[104] Matthew Baum, Dara Kay Cohen and Yuri M. Zhukov, “Rape Culture and Its Effects: Evidence from U.S. Newspapers, 2000-2013,” (forthcoming).

[105] Global Media Monitoring Project 2015, “Gender Inequality in the News 1995-2015,” November 23, 2015. http://cdn.agilitycms.com/who-makes-the-news/Imported/reports_2015/highlights/highlights_en.pdf

[106] Priyanka Dubey interview via Skype with author, March 28, 2016.