Commentary

A Smarter Way to Disagree

Commentary

In October, 2018, I stood inside a drafty community center tucked under a bridge over a quiet side street in otherwise bustling south London, nervously awaiting the arrival of Britain’s prime minister. Theresa May was joining an intergenerational quiz hosted by the charity I founded, The Cares Family, to launch the world’s first ever government-level loneliness strategy. Neighbors in their 80s gathered with friends in their 20s for cups of tea and giggles with a normally reserved PM, and to hear about her efforts to tackle what she called ‘one of the greatest public health challenges of our time.’

This moment of progress was the high watermark of years of advocacy and movement building from a growing number of organizations and individuals increasingly concerned about the insidious impact of loneliness resulting from the growing use of digital networks and other new forms of media and technology, and from accelerating change in our economies and how we live, work, and interact with one another. In particular, it was a response to the murder of British MP Jo Cox, who had spoken movingly about her own experience of loneliness: the Foundation set up in Jo’s honor worked diligently with campaign groups and closely with government to deliver a positive legacy out of unspeakable tragedy.

Jo’s experience of loneliness was personal, but she also understood that our disconnection crisis had public health and political consequences too. Indeed, while loneliness is most often technically defined as the gap between the quality and quantity of relationships people want and the quality and quantity they actually have, on an emotional level the feeling is akin to mourning, emptiness, yearning, even homesickness. As a social species, humans are wired to interact – we need connection like we need food or sleep – so when we do not feel part of a community, our bodies go into shock.

The result is that loneliness can lead to lasting mental health conditions including depression, anxiety, dementia, and addiction, and physical illness including strokes, heart disease, diabetes, even cancer and so-called deaths of despair. All told, loneliness is considered as bad for our health as obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes a day – and can increase the risk of early mortality by 26%. Indeed, if you have a heart attack, there are two lifestyle factors that drastically increase your chance of survival over any other: not smoking, and having good relationships that mean something to you.

In societies in which loneliness regularly affects millions of people, including the US where a third of adults report feeling lonely at least once a week, and the UK where 50% of adults say they ‘sometimes, often or always’ feel lonely, the impact of this crisis on our collective infrastructure is staggering. In Britain, one in 10 GP appointments is taken by a person with no other condition than that they’re lonely, costing an already overstretched National Health Service hundreds of millions of pounds. The impact is felt in the private sector too: in 2017, the New Economics Foundation estimated that loneliness costs UK employers between £2.2 billion and £3.7 billion per year in absences and productivity losses; in the US, where 12% of people reportedly have no close friends, this figure is an eye-watering $460 billion – an estimate that may even ‘fall short of the true cost.’

Increasingly, this ‘true cost’ is understood in terms of how loneliness can be both a cause and a consequence in complex cycles of social and political harm: educational inequality, homelessness, racial inequity, unemployment, domestic abuse, and a range of other social ills including othering, polarization and extremism. In recent years, it has even been shown that our disconnection crisis is leading to pronounced new vulnerabilities in democracy.

In 2022, the UK think tank Onward showed how rising loneliness amongst young people ‘is driving a generational slide away from democracy and social norms and towards atomization and authoritarianism.’ A previous Onward report had evidenced the relationship between loneliness, alienation and depleting trust, not just in politicians or the institutions of democracy, but in communities and in one another. Indeed, while today’s young people are ‘ostensibly the most socially conscious generations in recent history’, they are ‘easily the least socially attached to interpersonal networks or to their neighborhood,’ the report said.

In the US, meanwhile, former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has repeatedly shown the relationship between social connection and democratic values like opportunity, participation, inclusion, mutual belonging, and trust. Most recently, in his ‘parting prescription’ for America, Murthy wrote how loneliness is ‘fueling not only illness and despair on an individual level, but also pessimism and distrust across society which have all made it painfully difficult to rise together in response to common challenges.’ His ultimate invitation was for all of us to ‘choose community.’

Clearly, the strength and depth of evidence of our disconnection crisis has become irrefutable. My thesis is that this crisis has been driven by a number of converging forces.

Economic forces like globalization, deindustrialization, urbanization, gentrification, and inequality are unstitching once strong communities and social contracts rooted in work and place and leaving many people feeling left out, left behind, and that it is harder to interact with their neighbors in the places they call home but which don’t always feel that way.

Meanwhile, cultures are changing. Single occupancy living is rising, marriage rates are declining, faith participation is decreasing, trade union membership has fallen significantly over the long term, and the proliferation of choice has diminished opportunities for collective experience – and so, over the past forty years or so, collectivism has dissipated and individualism has thrived, while citizenship has been buffeted as consumerism has taken hold.

At the same time, political decisions have both underpinned and accelerated these trends. In the UK and the US, thousands of physical community spaces like youth clubs and libraries have closed, often replaced by global corporate entities and identities that people feel less of an affinity with – and sometimes replaced with nothing at all.

Finally, technology has changed how we interact. The average UK adult now spends 76% of their waking hours online, mostly staring at screens. Meanwhile, remote service delivery rather than face-to-face service delivery, message fatigue, and general demands on our time, leave many of us feeling – paradoxically, perhaps – unseen and unheard.

As economist Noreena Hertz showed in her 2020 book, The Lonely Century, all of these trends are deepening our loneliness crisis; as Derek Thompson wrote more recently in his landmark Atlantic article, The Anti-Social Century, the fact that we are spending more time alone than ever is ‘changing our personalities, our politics, even our relationships to reality.’ In the coming years, the proliferation of AI could make these layered trends even more severe.

And yet for all the evidence on the corrosiveness of loneliness on our lives, our communities, our public services, and our democracies, evidence about what really works to reduce loneliness is still widely perceived, at least in the halls of power, as thin. In straitened times, public and private sector institutions alike need clear rationales for investing in Murthy’s prescription for deeper community, but have not had the budgets – or perhaps always the political leadership – to invest in that evidence.

Thankfully, there is a growing body of research – often commissioned by community organizations themselves, conducted by independent evaluators, and verified by academic rigor – that shows how and why new twenty-first century connecting institutions can start to remedy our relational malaise. It’s research that continues to have some limits in scale, but that nevertheless underscores Harvard social capital doyen Robert Putnam’s thesis that ‘we came together a century ago and we can do it again.’

Over the past six months of my Shorenstein Fellowship, I have reflected specifically on the impact of my organization The Cares Family’s work between 2011 and 2023. I have reviewed three full-scale evaluations conducted between 2014 and 2019, as well as 20 studies on how we identified people at risk of loneliness and brought them into our intergenerational communities, reports on our pandemic activities, media features that analyzed the core ingredients of our work, and dozens of blogs and social media posts about why older and younger people alike who were involved in our intergenerational communities felt part of a changing world, rather than left behind by it. Specifically, my review found that:

1. Bringing older and younger people together to share time and new experiences can make people in both groups feel less lonely and isolated, happier, more connected to other people and in particular to people from different generations, backgrounds and experiences, and a greater sense of confidence and belonging in a changing world. In words that echoed time and again, many older and younger people alike said they felt ‘part of something bigger than their own lives’ as a result of being part of The Cares Family.

Her coming round is a chance to learn about her life and for her to learn about mine. She brings in a part of the outside world that I’ve lost touch with and now I feel like I’m part of the world again.

Quantitatively:

2. While there were a number of factors that led to this impact – not just on reduced loneliness, but on feeling part of the changing world – the intentionality around bringing people together from different generations, backgrounds, and life experiences, in inclusive, welcoming and non-judgmental environments and places that mattered to all participants, was shown to be key to achieving wider impact. Indeed, my review showed that:

We all have something to teach, and we all have something to learn. We are not all that different from one another.

3. There are replicable approaches that every community can adopt and adapt to reduce loneliness locally. These broadly fall under two key categories:

It has helped me understand the perspectives of people from different generations and see our similarities despite our differences.

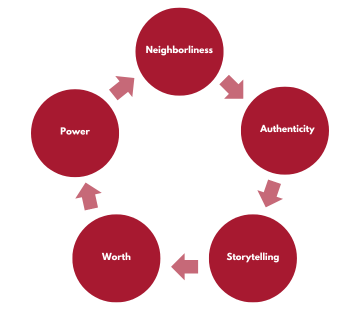

neighborliness, opening up the possibility of shared authenticity, giving people the courage to fail and therefore to share stories, leading to a sense of self-worth and then power, and ultimately reducing social deficits that make people feel isolated and lonely.’

neighborliness, opening up the possibility of shared authenticity, giving people the courage to fail and therefore to share stories, leading to a sense of self-worth and then power, and ultimately reducing social deficits that make people feel isolated and lonely.’4. In society at large, there remain stigmas, prejudices, and barriers to overcome to build connection in disconnecting times. In the last study of The Cares Family model conducted in 2023 and published in 2024, Service Designer and Churchill Fellow Savannah Fishel observed the importance of prioritizing safety in order to build connection and trust, noting the role of:

Clearly, these findings are limited insofar as they reflect the impact of just one organization’s model, and I recognize my own bias in focusing on The Cares Family in my review of the evidence of what works. There are thousands of wonderful groups in the UK, US and around the world, each tailored to their own communities’ needs, each in their own way doing something to tackle our loneliness crisis, each of which could be part of the answer in tackling our wider crisis of connection. This essay is not intended to be definitive. What my review has reminded me, however, is that governments, businesses and individual changemakers need to focus on what works locally, to recognize the contexts they are working in and the assets they have at their disposal, and to know that if we are to overcome a challenge of this size and scope, with such layered causes and consequences, a thousand more ‘flowers’ of connection will need to bloom.

Some of those new ideas are emerging within the HKS community itself. Over the past six months, I’ve been inspired by the many diverse and impactful initiatives that are being developed by students. For the remainder of 2025, I will continue to work with those students to help them develop their ideas. I’ll also publish a new report about the advocacy and movement building that led to that high watermark of progress in the UK in 2018, based on interviews with some of the leaders who made it happen, and including recommendations for next steps – to help ensure that a decade of impact can be just a beginning. For now, I hope the evidence above offers some insight for those in the HKS community and beyond who continue to think ambitiously about what’s possible – and to take the actions that will help us work together to build a more connected age.

Commentary

Commentary

Commentary