Product Management and Society Playbook

Reports & Papers

A paper by David Ensor, Joan Shorenstein Fellow (fall 2015) and former director of the Voice of America (VOA), makes the case for protecting and strengthening VOA as an independent journalistic voice in order to increase American soft power.

VOA’s news programming, which is funded by the U.S. government but remains by law editorially independent, reaches almost 188 million people a week in more than 45 languages, through a variety of platforms. Building upon Joseph Nye’s concept of soft power, Ensor argues that VOA is a valuable national security asset, and as such, could do much more for the U.S. if given additional resources. The way forward, Ensor writes, is to continue to build the trust of international audiences by providing honest coverage and partnering with local media – rather than simply advocating for U.S. policies. Ensor compares and contrasts VOA to other state-sponsored media, such as the BBC World Service, CCTV, Al Jazeera and RT (Russia Today), and provides specific recommendations to expand and improve VOA to reach more people in Russia, China, the Middle East and globally.

Read the accompanying article in Foreign Policy, “How Washington Can Win the Information War.”

Download a PDF version if this paper by clicking here.

Listen to Ensor discuss his paper on our Media & Politics Podcast:

“To be persuasive we must be believable; to be believable we must be credible; to be credible we must be truthful.” – Edward R. Murrow

In August 2014, ISIS attacks the town of Shinjar in northern Iraq, sending hundreds of thousands of members of the ancient religious minority known as the Yazidis fleeing up onto Mount Shinjar. Those not already captured are quickly surrounded. Information is scarce, but Voice of America’s Kurdish Service has a Yazidi reporter who soon hears from his people – with what is left of the power in their cell phones.

Hundreds of children are dying on the mountain, they tell him. There is no shelter, no food or water. Many have already been executed. Hundreds of young women are being held, raped and used as sex slaves. VOA’s exclusive details are picked up by regional media, alerting U.S. policymakers.

“I was talking with one of the ladies, for example,” says Iraqi-born journalist Dakhil Elias. “She was captured with fifteen hundred other women and children held prisoner in a school building. She was telling me: ‘Please bomb us! We want to die, not to stay here under ISIS.’” [1] VOA’s Elias is invited to two White House meetings with the president’s deputy national security advisor, where he shares some of the harrowing testimony.

Within days, the U.S. airdrops humanitarian aid on the mountain and then targets airstrikes against ISIS positions around it. The offensive allows Kurdish forces to reach the mountain and lift the siege.

The story of the encircled Yazidis underscores what key policymakers in the White House and State Department know well: the Voice of America (VOA) is a national security asset, and not only because it is a news organization of extraordinary breadth, depth and reach. Many of its best journalists hail from places such as China and Tibet, the Russian Caucasus, northern Nigeria, Venezuela, Iraq or Iran. They are indispensable experts.

Voice of America (VOA) is a national security asset, and not only because it is a news organization of extraordinary breadth, depth and reach.

Funded by the U.S. government, VOA is by law an editorially independent media organization. With an annual budget of $212 million, VOA has a weekly international audience of almost 188 million people; an increase of 40 percent in the past four years despite budget reductions in real terms each of those years.[2] It reaches them in more than 45 languages through television, radio, Internet and social media – and does so whether their governments like it or not.

VOA is an effort to harness and direct the nation’s soft power by exporting truthful, balanced journalism. This is a model of state broadcasting with a long history, credited with contributing to the peaceful demise of the Soviet Union.

There are influential voices in Washington, however, calling for change. They would make VOA a full-throated advocate for American policy. Their argument is that in the digital age, when there are hundreds of voices out there, everyone is going to have to “spin” in order to have real impact. The traditional model of journalism in the service of objectivity and balance is, they say, outdated. They repeatedly press to change VOA’s mission.

The U.S. International Communications Reform Act of 2014 proposed by Chairman Ed Royce (R-Calif) of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs would have required VOA to “promote” the foreign policy objectives [3] of the administration in power. While the House of Representatives passed the bill with bipartisan support, it expired at the end of the congressional session without Senate action.

Royce has a new version (HR 2323), introduced in this Congress, which seeks to reduce VOA from the full-service news organization it is now, to one which exclusively reports on U.S. related news. The bill would also create duplication and exacerbate an already unhealthy rivalry with three smaller sister U.S. broadcasting entities, by putting them under a different governing and oversight structure.

In 2013, a former senior official in the Bush administration went still further, arguing in congressional testimony that the VOA and its parent agency “should be part of the State Department” and that it “should not be in the journalism business but in the foreign policy business.” [4]

James Glassman, a former undersecretary of state and former chairman of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), the parent agency of VOA, believes that the BBG has two incompatible goals: “Its mission is contradictory and confused. The law asks it both to be a tool of U.S. foreign policy and an independent, unbiased journalistic organization, protected from government interference.” [5] Instead, Glassman argued, the “mission should be the same as that of the State Department itself: to achieve the specific goals of U.S. national security and foreign policy.” [6]

At a July 2015 management retreat a senior official at the BBG proposed reshaping and redirecting the work of VOA and its sister organizations under the policy goal of “countering violent extremism.” A number of VOA journalists argued such a move would break down the “firewall” between journalism and policy, damaging VOA’s credibility. The proposal was quietly shelved but continues to have influential supporters in Congress and the bureaucracy.

The West today faces information challenges from the likes of Russia’s global TV broadcaster RT, China’s CCTV and Iran’s Press TV, not to mention the need to combat Internet recruitment drives by terrorist groups. The age of global satellite channels and digital media is reshaping the media landscape, creating extraordinary new challenges and opportunities. Yet rather than focusing fully on how to respond to those challenges and take advantage of the digital communications revolution, Washington has instead been cutting budgets and rehashing an old debate about VOA’s mission.

What is the proper role of the Voice of America in a world where Vladimir Putin “weaponizes information” [7] and terrorists recruit globally on the Internet?

In today’s media environment, are state broadcasters that advocate for their governments delivering larger audiences and greater impact than those that work to report the news as objectively as possible?

In the digital age, should VOA become a policy-driven advocacy voice? Or, should VOA continue to offer balanced, truthful journalism? And if the choice is journalism, how can we make it more effective?

These are the important questions this paper seeks to address.

Funding international media is just one of many tools at the disposal of governments to attract and persuade foreign publics and governments. Harvard professor Joseph Nye, who coined the term “soft power” in 1990, says the need to understand and use it effectively is only growing. “In this confused, complex multipolar world, the limits of hard power – the use of force, threats, sanctions or payments – are becoming more obvious.” [8]

The sources of American soft power range from Hollywood to Harvard, from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to Apple, Facebook and Twitter. Also on the list are the U.S. Bill of Rights, and America’s reputation as a nation of immigrants. On the other side of the balance sheet are aspects of American life or policy that repel foreign publics, such as too many guns on our streets, and a perception that the U.S. wages too many wars. Portland Communications, a British consulting firm, recently designed a tool to measure and evaluate a nation’s soft power. In 2015, it published the “Soft Power 30” report, a list of the nations that wield the greatest soft power. Britain wins. America comes third. China is 30th, and Russia does not make the list.[9]

Many of the efforts by the U.S. government to harness American soft power and persuade global audiences to follow this country’s lead are run by the State Department under the heading of Public Diplomacy. Richard Stengel, the current undersecretary of state for public diplomacy, has focused much of his attention on countering terrorists’ recruiting messages online. With a budget of just $5.8 million,[10] the State Department’s Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC) works through websites and online chat rooms, collaborating with partners in the Arab World such as the Sawab Center in the UAE.

“We have a campaign,” Stengel says, “which is using direct testimony from dozens and dozens of young men and women who have come back from Iraq and Syria and said the Caliphate is a myth. You know, ‘I was abused there. They’re not religious. They’re venal and money-grubbing.’ So that type of campaign to refute their disinformation is the kind of thing that we’re doing.” [11]

Watch video: VOA’s Pamela Dockins interviews Richard Stengel.

Counter messaging work with partners in the Middle East and North Africa is urgent and under-resourced, but it is important not to lose sight of the longer game in which credibility is key. That is where journalism comes in.

Journalism as U.S. Soft Power

VOA was founded in 1942, using a borrowed British transmitter to broadcast shortwave radio programming in German. The founding concept was taken from the BBC. On the first broadcast, it was said: “The news may be good for us. The news may be bad. But we will tell you the truth.” [12]

Watch video: The first broadcast of Voice of America.

The signature of President Gerald Ford in 1976 on the VOA Charter codified that promise into law. Sponsored by Senator Charles Percy (R-Ill) and Representative Bella Abzug (D-NY), it was passed after battles with the Nixon White House over what VOA could say on the air about the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal.

The charter requires VOA journalism to be “reliable and authoritative,” and to report news that is “accurate, objective and comprehensive.” It also requires that VOA “present the policies of the United States clearly and effectively” and present “responsible discussion and opinion on these policies.” [13]

Rather than advocating for the policies of the current administration, the concept is to seek credibility with coverage that is honest about America’s own debates and controversies, and to present all sides of the argument. Thus VOA reported fully on stories like the revelations of Edward Snowden about NSA surveillance, and on the protests in Ferguson, Missouri and other cities against police killings of young African Americans. It also televised – live to Iran, with Farsi translation – Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech before the U.S. Congress against the Iran nuclear deal, even though he was attacking a key aspect of President Obama’s foreign policy.

Given the existence of CNN and other international news channels, some ask what is the need for a VOA? The answer is that commercial broadcasters run on the profit motive. There is little profit in international broadcasts in Farsi, Mandarin, Hausa, Bambara or for that matter English programming designed specifically for key African audiences. But U.S. national interests are served by targeting audiences in parts of the world where reliable news is hard to find, or where information about U.S. policy is often served up with a strong anti-American tilt. VOA news programs and websites delivered in multiple languages deepen international understanding of American policies and values and hence promote freedom of speech and democracy. Also, VOA journalists can make news judgements independent of market considerations. If a dozen new health clinics open in Afghanistan, for example, that is news Afghans want to know about, just as much as the last Taliban attack. Commercial media are sometimes accused – not always fairly– of an “if it bleeds it leads” approach, which is far from the way non-commercial VOA makes its coverage decisions.

The U.S. is one of relatively few nations on earth not to have a state broadcaster on the air domestically. As a result, few Americans – and few of their elected representatives – know that VOA is one of the world’s largest, most influential media organizations. They are more likely to know about the even bigger British broadcaster that it was designed to emulate.

“Don’t expect too much in the early days,” warned John Reith, founder of the BBC World Service, in 1932. “The programmes will neither be very interesting, nor very good.” [14]

Since then, however, the BBC World Service has vastly exceeded Reith’s early expectations. With a total global audience of more than 300 million people, the BBC World Service saw growth across all platforms last year: television, radio, mobile and digital. Total audience growth was seven percent last year, and the director-general of the BBC has set for the World Service an ambitious target audience of 500 million people by 2022. The British government recently increased the BBC’s budget by over $400 million over the next four years to help it meet that half billion audience target, responding to growing information challenges in places like Russia, North Korea and Nigeria.

Britain has benefited enormously from the BBC World Service’s global reach. In 1998, then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan described it as “Britain’s greatest gift to the world” [15] and Aung San Suu Kyi cited the BBC’s radio broadcasts as a “lifeline” [16] during her 15 years of house arrest in Myanmar. In 2013, the World Service commissioned a survey of international business leaders in an attempt to quantify this soft power influence on Britain’s economic wellbeing. Two thirds of the executives surveyed said that the BBC was the main way they found out about the U.K. Moreover, the more they watched and listened to the World Service’s programs, the more likely they were to do business with the U.K. [17]

Britain has benefited enormously from the BBC World Service’s global reach… Two thirds of [international business leaders] surveyed said that the BBC was the main way they found out about the U.K. Moreover, the more they watched and listened to the World Service’s programs, the more likely they were to do business with the U.K.

The BBC Royal Charter and Agreement with the secretary of state articulates the objectives for the World Service, including “the provision of an accurate, unbiased and independent news service covering international and national developments.” [18] Former Director of the BBC World Service Peter Horrocks believes these principles are not only key to the global success of the organization, but underpin the soft power benefit for the U.K.

“People are often struck by the difference between the claim of impartiality and simultaneously delivering British values to support the U.K.’s soft power,” says Horrocks. “But it’s by being impartial that the World Service helps promote Britain…We absolutely reflect British values, and British values of fairness and impartiality are absolutely the bedrock.” [19] Horrocks is now the vice chancellor of the U.K.’s Open University.

“The BBC is a public institution but not the government’s lackey,” agrees analyst Martin Wolf, writing in the Financial Times. “That is what made it trusted in the U.K. and around the world.” [20]

Watch video: Peter Horrocks discusses the BBC and soft power.

In London – just as in Washington, D.C. with VOA – there are those who would prefer an advocacy role for the BBC World Service; for it to explicitly promote the U.K.’s agenda on the world stage. In May 2013, the House of Lords appointed a Select Committee on Soft Power and the U.K.’s Influence to examine the question.

The committee’s final report was resounding in its endorsement of the importance of the BBC World Service to Britain’s soft power. Furthermore, the peers concluded that “the BBC’s independence from government is an essential part of its credibility.” [21]

Horrocks believes that any move to “politicize” the World Service would be “utterly fatal” [22] for the organization.

The 21st century however, has witnessed a marked shift in the international media landscape, particularly with the rise of state-funded media challengers such as Qatar’s Al Jazeera Arabic, Russia’s RT, China’s CCTV and Iran’s Press TV.

These new media outlets have adopted a set of reporting principles and editorial policies at odds with the BBC World Service model. Often favoring “advocacy” including spin, sins of omission and even lies over the goals of balance and impartiality, they have courted controversy with their promotion of their respective states’ policy agendas.

“Everything in Russia’s media changed with Putin,” explains Vasily Gatov, a former Russian journalist who fled to the United States in the early 2000s and is now a visiting fellow at the USC Annenberg Center for Communication, Leadership and Policy. “Under Yeltsin, there was much less interference. Much less money, too.” [23]

Since President Vladimir Putin first assumed office in May 2000, he has overseen a policy of effective “renationalization of the media” [24] within Russia. In the first five years of his rule, 70 percent of electronic media organizations, 80 percent of the regional press and 20 percent of the national press were brought under state control.

With Russia fractured and seeking its post-Cold War identity, Putin adopted a conscious strategy to consolidate the federal state’s authority. He uses media to frame Russia’s place in the world to a domestic audience and define Russia’s contemporary values. Putin speaks quite candidly about the Russian media as a “formidable weapon that enables public opinion manipulations.” [25]

Television broadcasting is the most effective weapon of all. Owned by the All-Russia State Television and Radio Company, Russia-1 claims domestic weekly audiences of 75 percent of all Russians living in urban areas.[26] The channel has helped drive a record-high approval rating of 89 percent for President Putin in June 2015, as measured by the Levada Center in Moscow [27] – one of the most respected and independent think tanks in the country.

On the home front, Gatov says, “these efforts [under Putin] have been highly effective”[28] in shaping the public narrative. A poll conducted by Levada found that 82 percent of Russians believe the Ukrainian army brought down Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 in July 2014.[29] Just 4 percent of Russians blamed the Donbass People’s Militia, and 3 percent thought pro-separatist Russian rebels were responsible.

Peter Pomerantsev is the author of Nothing is True and Everything is Possible, a book describing the decade he spent working in the country’s TV industry.

Watch video: Peter Pomerantsev discusses Russian state media.

“TV remains the Kremlin’s most effective tool to engage Russians but also beyond Russian borders to Russian speakers abroad,” says Pomerantsev. “The motif is remarkably similar: chaos is everywhere, but Vladimir Putin is bringing stability… Putin is shown as brave, standing up to Obama and the West. It’s the adventures of Vladimir Putin on TV.” [30]

The theme resonates in Russia, where polls show the public also overwhelmingly supports state censorship. Studies conducted by the All-Russian Public Opinion Research Center in 2006 showed that 63 percent of Russians support Kremlin censorship of the mass media.[31] Only 9 percent of respondents considered censorship unjustified under any circumstances. With the rise of digital media, a University of Pennsylvania study found that half of all Russians believe information on the Internet needs to be censored, and four in ten believe foreign countries are using the Internet against Russia and its interests.[32]

Part of the reason why the Kremlin media’s narrative is so well accepted within the Russian Federation may be because on television, radio and in print, most of its competition has been eliminated. President Putin has effectively closed off domestic radio and television outlets in Russia from foreign programming that had flourished on local media under his predecessor Boris Yeltsin. The one exception is online. VOA, Radio Free Europe, the BBC and Deutsche Welle must now rely primarily on Internet-based journalism to reach young Russians in the digitally-savvy major cities. This is a key audience for the future, but modest in numbers compared to TV’s enormous reach in Russia.

Watch video: The Adventures of Vladimir Putin.

RT: Russia’s Foreign Push

Despite big budgets and a targeted strategy, President Putin’s international media strategy has yielded less evident results than his domestic one. Russia Today, now known simply by its acronym RT, was launched in 2007 with a vision to promote the Russian perspective on global events to foreign audiences. With Kremlin funding in excess of $80 million in 2007, RT’s annual budget has soared to almost $400 million in 2015,[33] excluding additional revenue generated through advertising. In the space of less than a decade, the Russian government has spent more than $2 billion on RT.[34]

RT claims a global reach of 630 million people in 100 countries, carried by 22 satellites and over 230 operators.[35] It operates channels in English, Spanish, French, German and Arabic, and claims to be the most-watched news network on YouTube with more than two billion views in total.

After the shooting down of Malaysian Air flight MH17, the world’s media reported on mounting evidence that the weapon used was Russian made and could have been fired from a town held by Russian-supported Ukrainian rebels. In the early days after the shoot down, RT cranked out a new theory for almost every news cycle on who could have been responsible. On July 17, 2014, RT’s website led with the headline: “President Putin’s plane might have been the target for Ukrainian missiles – sources.” [36] Another RT story suggested it was a CIA plot. Conscious efforts were made to discredit the claim that Russia could be implicated.

In September 2015, the U.K.’s Office of Communications (Ofcom) sanctioned RT for this coverage, ruling that it had breached national rules on accuracy and impartiality. After an investigation, Ofcom found that RT had breached the U.K.’s broadcasting code on four occasions in three “misleading or biased programmes on the conflict in Ukraine.” [37]

Does RT Have Impact?

Many analysts have questioned the audience numbers provided by RT. Evidence from a RIA Novosti internal document leaked by former employees after the outlet’s enforced closure in December 2013 shows that RT’s 630 million audience reach claim does not represent the actual number of viewers for the channel. “In reality that number is just the theoretical geographical scope of the audience,” the document says: in other words RT conflates potential audience reach with actual viewership.

International viewers’ perception of RT’s coverage as biased appears to have limited its share of global audiences.

RT has declined to make public any of the detailed audience research data it has collected, however, there are indications available as to the size of RT’s audience in some major overseas media markets. In the United States, for example, RT does not even make Nielsen’s ratings list for media outlets. A Nielsen press official said that RT’s American audience is too small to be measured. [38]

In the U.K., as of May 2013, RT occupied 175th place out of 278 channels in Great Britain with approximately 120,000 daily viewers. As highlighted by The Daily Beast’s Katie Zavadski, RT’s audience has shrunk since then. Recent data from the U.K. Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board (BARB) shows that RT has less than 100,000 viewers a day,[39] with less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the total viewing population. RT likely has larger audiences in countries other than the U.S. and Britain, but the 630 million figure is clearly intended to mislead.

Why does RT exaggerate its audience numbers? One explanation, beyond the stated objective of projecting RT as a successful international media organization, may be rooted in domestic politics and jostling for financial resources from the Kremlin. RT was created as a subsidiary of parent company RIA Novosti but eventually came to subsume the organization. In December 2013, President Putin issued a surprise decree that dissolved RIA Novosti and the state-owned Voice of Russia, further centralizing state control of the Russian media sector.

International viewers’ perception of RT’s coverage as biased appears to have limited its share of global audiences. RT’s audience within the U.K. during the Ukraine crisis is one example of this. This began in December 2013, when protests began in Kiev’s Independence Square over President Yanukovich’s failure to sign a trade deal with the EU, and intensified with Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March and escalation of the conflict in Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk in April. As the data below shows, RT’s average daily audience in the U.K. dropped consistently during this five-month period, falling from a high of 137,000 in December 2013 to just 90,000 in May 2014.[40]

While other factors may have contributed to RT’s declining share of the U.K. audience – and one must be cautious about the inference of causal conclusions from correlative observations – this data does suggest at the least that RT was less effective as a tool of Russian soft power when its content and perspective became more evidently biased.

Pomerantsev believes that the Kremlin knows it will never compete with leading international news broadcasters and that audience numbers aren’t necessarily the priority. RT exists, he says, to contribute a Russian perspective within an international media market increasingly characterized by partisan voices. Even more importantly, RT seeks to raise doubts about the narrative found elsewhere:

“Russia’s approach [with RT] is to say, ‘It’s pointless to go for the truth, because there are so many truths out there.’ So they play on a negative. People get split off into silos. It doesn’t matter to RT if they’re winning over the mainstream viewers or not,” Pomerantsev says. “It helps to dismantle and fracture a ‘common narrative.’” [41] Or, as Leon Aron, a Russia scholar and BBG governor put it at a recent Senate hearing:

The RT television network aims not so much to “sell” what might be called the “Russia brand,” but rather to devalue the notions of democratic transparency and accountability, to undermine confidence in objective reporting, and to litter the news with half-truths and quarter truths.[42]

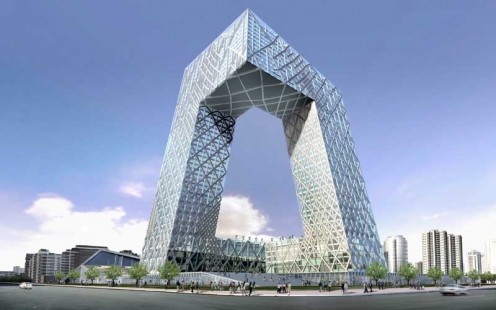

China Central Television (CCTV)’s headquarters stands in stark contrast to the rest of the Beijing skyline. Visible from much of the city, the dramatic modernistic structure soars to 800 feet and dazzles in the sunlight. It looks different from different angles: “sometimes big and sometimes small, sometimes strong and sometimes soft.”[43] Ten thousand CCTV staff work within the headquarters, a building that, together with the Television Cultural Center, cost an estimated $1.2 billion to construct. It is a building designed to make a bold statement.

The Chinese government’s intentions for CCTV are similarly ambitious. Initially founded in 1958 as a domestic party propaganda outlet, it has grown into an international state media service, boasting sizeable offices in Washington, D.C. and Nairobi, in addition to Beijing. It operates a further 70 international bureaus around the world.[44]

The expansion of CCTV began in 2001 with the government’s announcement of a “going out” policy to expand foreign language broadcasting services. The initiative “has been designed to enhance China’s image and convey its perspective to the world,” [45] and is part of a multi-billion dollar investment in enhancing China’s soft power, which has also included the opening of ninety “Confucius Institutes” around the world, providing information and classes on China’s history and culture, as seen by the Chinese Communist Party.

The Beijing leadership sees CCTV as a key part of a long-term effort to change the world’s perception of China. A communiqué published by the Communist Party Central Committee in October 2011 declared that “to some degree, whomever owns the commanding heights of cultural development, and soft power, will enjoy a competitive edge internationally.” [46]

While the official budget of CCTV is a closely guarded state secret, Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post has reported investments of over $7.1 billion.[47] Researchers at Columbia University’s School of Journalism allege that CCTV’s annual budget is almost 20 times that of the BBC.[48]

“The Chinese got into the game rather late,” says Jim Laurie, a seasoned American television journalist who joined the faculty of Hong Kong University in 2005 and works as a consultant to CCTV, among other global channels. Laurie believes that the CCTV budget is less than is often claimed. He says the Chinese government saw the early success of one new state-funded satellite television outlet in particular and sought to respond with the Chinese equivalent.

Like RT, CCTV has been accused of bias in its coverage. Some argue that it is simply a propaganda arm of the Chinese Communist Party.

It was “in part the Al Jazeera effort that prompted the Chinese to say, ‘we ought to get into this game…these other entities have an aggressive international television presence and we don’t. We need to move in that direction,” Laurie says.[49]

Like RT, CCTV has been accused of bias in its coverage. Some argue that it is simply a propaganda arm of the Chinese Communist Party.

“Clearly, the editorial policy is to ensure that the Chinese perspective is heard and represented,” acknowledges Laurie. “They’re very keen to project what they want to project vis-à-vis the economy, for example. They wish to project that the economy, although it is struggling right now, is not quite as bad as the naysayers say it is.”[50]

On some issues, that perspective is even more evident on CCTV. A special report titled “Inside Tibet” covered a number of issues – the region’s nature reserves, rising temperatures and caterpillar fungus – but neglected human rights abuses and public self-immolation by scores of Tibetans in protest of them.

“Should I go to CCTV if I want to know what’s happening in Tibet?” Laurie was asked. “The short, frank answer is no. If you want to find out what the Beijing government thinks about Tibet, then the answer is yes.” [51]

Laurie says he believes “the days are gone when there was that dedicated audience that would tune in to the BBC World Service or the old VOA and say, ‘ah, this is where we get the truth.’” Instead, he says, today “the job of a consumer is to listen to as much of the spin as possible and then make a judgement.”[52]

Watch video: Interview with Jim Laurie.

An opposing view comes from Boston College Professor Martha Bayles, who finds “glaring omissions and pro-regime puffery” on RT and CCTV. She writes that “these channels embrace the headline news formula, not only because it makes money, but because it lets them present an ‘open’ modern face to the rest of the world while at the same time slanting coverage in an ideologically approved manner.” [53]

CCTV’s investment in African media markets provides an interesting case study on which model works best. The Kenyan capital of Nairobi was the first broadcast hub for CCTV outside of Beijing, which speaks to the geostrategic importance attached to Africa for the Chinese government.

China invested in building state-of-the-art studios in Nairobi, poaching many of the best known and most respected local anchors. Official budgets remain unknown, but this likely represents a substantial financial outlay from Beijing. A local newspaper editor described an evident “full-on charm offensive” [54] in the region by the Chinese media. Yet for all CCTV’s investment in the region, it attracts relatively limited audiences. TV audience data from 2013 revealed that, in the previous week, 52 percent of Kenyans had watched local station Citizen TV – the most popular in the country. 17 percent had watched CNN and 7 percent had watched the BBC World Service. By contrast, just 2 percent had tuned in to CCTV.[55]

There are likely to be a variety of reasons for CCTV’s relatively limited following. It is new compared to the likes of the BBC and CNN, for instance, but audience numbers two years after launch are lower than might have been expected given the resources apparently invested in the service.

African journalists formerly with CCTV have alleged Chinese interference in the service’s editorial line. Instructed to provide “positive news” on China and to omit negative words, such as “regime,” journalists were instructed to ignore countries that have diplomatic relations with Taiwan, such as Swaziland.[56] Chinese demand for ivory could not be mentioned in stories about poaching in Africa. Self-censorship is also allegedly a problem within CCTV. One journalist recalled how human rights questions had to be left off the agenda in a televised interview with an authoritarian leader. “I knew it would be cut out of my story, so I self-censored,” he said.[57]

Evaluating the impact of CCTV is even harder than it is for RT, given the Chinese government’s unwillingness to release budget or audience data for the outlet. Still, some have argued that China’s authoritarian domestic governance and Beijing’s tight control over CCTV’s editorial line will inevitably limit the outlet’s effectiveness and the impact of the state’s investments in initiatives to build soft power.

“What China fails to understand,” argues China scholar David Shambaugh in an article in Foreign Affairs, “is that despite its world-class culture, cuisine and human capital, and despite its extraordinary economic rise over the last several decades, so long as its system denies, rather than enables, free human development, its propaganda efforts will face an uphill battle.”

“Soft power,” says Shambaugh, “cannot be bought. It must be earned.” [58]

In 1996, the Emir of Qatar wanted to shake up his region and augment Qatar’s prestige and soft power by building something new in the Arab world: a government-owned television news network with the goal of fact-based journalism – not government spin. Al Jazeera Arabic quickly became a sensation in the region, and a ratings winner. Many have argued that Al Jazeera’s creation contributed to the Arab Spring. In English, Al Jazeera America has a relatively small audience but has earned respect for the quality of its journalism.

In a cacophonous digital world, with so many channels and mobile apps now vying for attention, could journalism with the goal of objectivity be on its way to extinction?

But in 2013, when Al Jazeera’s Arabic-language service began to broadcast heavily-biased content in favor of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, it paid a price; losing substantial audience share, a portion of it to BBC Arabic. “When things started to turn in Egypt,” says Peter Horrocks, “there was a huge swing against Al Jazeera.” [59]

A Gallup survey conducted in Egypt in June, 2015 for the BBG indicated that Al Jazeera Arabic lost almost seventy percent of its audience, as compared to the survey done in 2013.[60] While many other existing satellite news channels also lost audience due to the emergence of a number of new Egyptian free-to-air channels, none saw a drop as dramatic as that of Al Jazeera Arabic.

“That’s where, by being steady in its approach to the story and in being even-handed,” the BBC won respect, Horrocks says.

Still, in a cacophonous digital world, with so many channels and mobile apps now vying for attention, could journalism with the goal of objectivity be on its way to extinction?

The BBC’s former World Service head says “no” but he was hardly surprised by the question: “It’s challenged because people have got alternatives,” says Peter Horrocks. “I’ve thought about it long and hard and was tempted to lurch in these other directions, but it would be utterly fatal for the BBC. Any organization with a claim to that objectivity loses it at its peril.”[61]

The era of digital media has just begun and it is early yet to assess its impact. The number of global Internet users has tripled in the last decade. By 2020, there will be 6.1 billion smartphone users in the world. The digital revolution is a double-edged sword, creating new opportunities to consumers of news and information along with significant challenges. People have many more choices, and can hear from more points of view. Digital media offers a platform for a conversation between news media and audiences. The audience can talk back to journalists and provide news themselves – photographs, video, unique perspectives. But the Internet has also destroyed the business model of many newspapers around the world, closing down important voices and reducing the number of well-paid jobs available in print journalism. It has also caused the reduction of many TV and radio news budgets.

For government-funded international media, however, like VOA, the BBC World Service, Deutsche Welle and France 24, it is a force multiplier. With TV and radio broadcasting largely blocked in Russia, for example, Western international media increased their digital efforts after the invasion of Crimea.

Germany’s Deutsche Welle Russian language news sites are now updated around the clock, churning out about 80 new articles a day. They receive 15 million impressions a month, according to Deutsche Welle, counting MSN, Facebook, Twitter, You Tube and similar platforms.

Digital media also make possible remarkable new ways to cover what is going on in a closed society. In June 2009, Neda Agha-Soltan was shot dead in the streets of Tehran. Just 26 years of age, she was an innocent bystander during the Green Revolution protests against the disputed electoral victory of President Ahmedinejad. Camera phone images of her face, bloodied from a bullet wound on her forehead, were seen the world over. The event has been described as “probably the most widely witnessed death in human history.” [62]

The same phenomena can also be turned on its head, however, by intelligence services in police states that quickly assess the vulnerabilities of crowd-sourced news gathering. Again in Iran, a passport-style photo of Taraneh Mousavi was sent to western journalists in July 2009 with assertions she had been tortured and killed. Some news organizations took the hook and ran stories. Their credibility was hurt when her family soon emerged to say she was alive and had never even been arrested.

In short, digital media are thus far a mixed blessing – leading to innovation and broader distribution, but also leading to ever shorter news cycles and shorter attention spans. The new more easily trumps the proven than was the case before the world of Twitter feeds. Short memories and shorter news cycles make it easier than ever before to confuse audiences.

Going forward, author Anne Applebaum expresses a further concern that “just as in the last period of communications innovation, when loudspeakers, radio, and movies were used effectively by Hitler and Mussolini to manipulate people in Germany and Italy, so too digital media could potentially be used by a new generation of fringe populist authoritarians to gain power in democracies.” [63] The Net Delusion, a 2011 book by Byelorussian author Evgeny Morozov warns of the “dark side of Internet freedom,” and quotes sociologist Manuell Catells: “The Internet is indeed a technology of freedom, but it can make the powerful free to oppress the uninformed.” [64]

Still, overall, digital communications should make for a better informed world. “Great Firewalls” notwithstanding, it is now much easier to spot check whether reports are accurate or not. It is also more difficult to get away with spinning different versions of one story to different audiences.

Media markets are constantly evolving and that process is accelerating. What works for VOA is to be firm on journalistic values but flexible and agnostic on how best to reach audiences.

To reach audiences, each country and language requires a tailored approach, and readiness to move to new platforms as they emerge. Change is constant, but three general types of markets for U.S. produced international media can be identified:

Market 1: Denied Areas

In “denied areas,” where authoritarian states censor media and attempt to keep their populations ignorant and easily manipulated, old fashioned shortwave radio often remains the most effective way to reach people. While radio jamming works, and has, for example, blocked shortwave radio from reaching much of the Chinese mainland, it is expensive and imperfect, especially outside the cities. Shortwave radio only requires a simple device to hear, though admittedly one which is gradually falling out of favor and commercial production. To increase VOA’s reach to the people of North Korea, programs have recently been added to medium wave (AM) radio transmitters in South Korea, though it will take time to know how much this approach helps, because one of the few ways to gauge audience attitudes in the country is to interview North Korean defectors.

Satellite television, direct-to-home, is an enormously effective platform in denied areas such as Iran, and to some extent, China. BBG audience data from 2015 highlighted that VOA has a weekly audience of 14.2 million people in Iran. This represents almost 25 percent of the country’s total number of television viewers.[65] That is true even though the satellite dish needed to receive the broadcasts is illegal to own. In China, VOA Weishi satellite TV news programming, by improving quality and broadcast time, managed to increase its weekly audience size by sixteen times to 1.225 million a week from 2009 to 2014. Features such as “Error 402” – what the Communist Party censored on the Web today and “History’s Mysteries” – Chinese history they don’t teach in school – are particularly popular with Chinese audiences.

For digital media in denied areas, investment in Internet circumvention techniques is often crucial.

VOA’s Russian-language television news program “Current Time,” co-produced with Radio Free Europe, which was created after the Russian invasion of Crimea, reaches an estimated two million viewers inside the Russian Federation through live streaming on the Internet and through privately owned satellite dishes. It reaches millions more in places like Ukraine, Moldova and Lithuania through terrestrial broadcast on 25 partner stations in nine countries, according to the BBG.[66]

For digital media in denied areas, investment in Internet circumvention techniques is often crucial. The BBG spent $14.5 million [67] in FY2014 to help Internet users get around the Great Firewall to read news and blogs published by VOA and its sister company Radio Free Asia (RFA). It is a cat and mouse game. Companies like Tor and Psiphon continually create new work-arounds, allowing determined Chinese Internet users to know what is being reported around the world that the Chinese government has tried to keep from its people. The number of weekly users of VOA Mandarin rose about tenfold over five years, from 215,600 in 2009 to 2,265,000 in 2014.[68]

In November 2012, the new Chinese Premier Xi Jin Ping spoke of his “Chinese Dream” to “unite all Chinese power” and return Beijing to the position it once held as capital of the world’s most advanced and civilized nation. VOA commentator Sasha Gong posted a reply on Twitter saying Xi’s Chinese Dream was a collective dream with a single color, while her “American Dream” is an individual’s dream with a multitude of colors.

“I had been dreaming of free speech since I was a child” the former Chinese dissident wrote, “but only in America did I find a huge microphone for myself.”[69]

Despite the Great Firewall maintained by Chinese censors, Sasha Gong’s tweet went viral in China. Reposted 140,000 times, it had over sixteen million views within a week.

Market 2: Maturing Media Markets

What works best in maturing media markets is to partner with successful local broadcasters and websites, helping to enhance their coverage of the United States and other international news. VOA calls this the “affiliate model” and it is by far the largest reason VOA audiences have grown by 40 percent in the last four years. The goal is not to produce all the news, but to be part of the conversation with important audiences when it comes to U.S. policy and major international stories. This model can help ensure that international reporting about this country is fair and correct.

VOA is affiliated, for example, with eight out of eleven of Indonesia’s major radio and television companies; with one of Africa’s biggest news networks, Channels TV of Nigeria; and with Azteca TV, one of Mexico’s largest television news channels. Last year alone, the audience in Mexico rose by ten million people to 24.4 million. Over the last four years, VOA’s audience in Latin America rose from about three million to over 35 million people each week, largely thanks to the success of the affiliate model.

Here is how the model works: a VOA reporter whose origins may have been in the country he or she is reporting to, but who was trained in journalism in the U.S., reports regularly, live or in packaged form, on the local station’s news shows. Thus, the reporter is able to speak to millions in the partner station’s audience about news of interest to them. VOA Latin America journalists appeared live from the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, during the unrest there, from Boston after the 2013 marathon bombing, and from Rome, upon the selection of the first pope from South America.

VOA partners with multiple stations in Ukraine, providing news about the administration’s take on the Russian invasion of Crimea and Russian support for separatists. In Erbil, Iraq VOA Kurdish reporters can be seen on the local station’s evening news reporting on the latest developments in U.S. policy toward the terrorist group ISIS, as well as airing courageous coverage of the fighting against ISIS collected by VOA’s Kurdish stringers.

In 2009, VOA created VOA Direct, an online platform that enables affiliate stations to quickly find VOA original reporting, video and sound for their use. It has since been renamed BBG Direct, and expanded to include material from sister entities.

Market 3: Underdeveloped Markets

In underdeveloped markets, international media are increasingly skipping straight from the shortwave radio as a distribution platform to the device that even Afghan goatherds now have: the mobile phone. In northern Nigeria, for example, as shortwave radio audiences decline, VOA has deployed a mobile application called Dandalin, which detects a user’s device and adjusts accordingly, offering news highlights, sports and lifestyle information with video and audio options, tailored to a range of mobile devices.

The addition of Dandalin to VOA Hausa’s desktop websites put total online usage at over 18 million per week. That strong and growing reach gives VOA influence. Nigeria’s new President Muhammadu Buhari chose to grant his first interview in office to VOA, saying: “I am an avid listener of VOA, because you are fair, professional and balanced, which all add up to the fact that you are the station I love to fear.”[70]

In some markets, where due to poverty, instability or other causes there is little or no media infrastructure and no local broadcaster who would be a suitable affiliate, it makes sense for the U.S. to build and maintain its own FM transmitters and towers. Occasionally an ambassador will agree for the FM equipment to be placed within the security of embassy grounds.

The BBG has been opening 24-hour FM streams for VOA in Africa. When private radio stations were torched during the attempted coup in Burundi in May 2015, VOA FM Bujumbura was the only local source of news on air. U.S. broadcasters quickly expanded call-in shows and newscasts in Kirundi, the language spoken by more than one-third of the population.

When private radio stations were attacked during an attempted coup against transitional leaders in Burkina Faso in September 2015, VOA FM Ouagadougou broadcast live from the gates of the presidential palace and as its reporters ran from a counter demonstration under fire. When soldiers came to break-up the mutinous presidential guard, the coup leader announced his surrender on VOA.

In Pakistan’s Pashtun tribal areas along the border of Afghanistan, VOA discovered that even in the poorest villages, satellite dishes are sprouting up, and people want to be able to see who is talking to them on its highly trusted Deewa Service. Some radio shows are now simulcast on satellite TV to serve this demand. The same is true in Haiti.

Be Nimble

New foreign policy challenges constantly emerge, requiring international media like VOA and the BBC to move quickly. Within days after the May 2014 coup that took place in Thailand, the BBC had a “pop-up” Facebook service on line, offering news in Thai, a language the broadcaster had not previously used in many years. BBC officials say the data suggests a relatively limited financial investment yielded substantial large impact, as Thais sought reliable information in a time of great uncertainty.

When Islamists with guns moved southward in Mali in February 2012, knocking out radio stations including VOA affiliates, the Obama administration asked VOA to move quickly. VOA supplemented its traditional Africa-wide French broadcasts with radio news updates in a new local language – Bambara. Overnight, this allowed VOA and its affiliates in Mali to expand their reach.

When terrorists in Mali attacked the Radisson Blu in November 2015, VOA FM Bamako broadcast live from the hostage standoff with local reporters in French and Bambara. American businessman Terry Kemp told VOA he saw shooting across the street, “four to five individuals running towards us and shooting. We immediately ran back inside. As we were going up the steps, the glass was shattered.”

Give Them What They Want

In terms of programming, there is a tendency in the bureaucracies of state-funded media to try to impose what policymakers want, rather than what a particular audience may prefer. This is a mistake. If you don’t give the target audience and consumers what they want and need, you will not reach them in any numbers. This recommendation may appear self-evident, but in the wake of some policymakers’ efforts to promote “messaging,” it should be underscored. The role of policymakers should be at a higher level: determining where VOA and its sister entities should do their work, and at what funding level. Deciding on a market strategy and what exactly to say should be left to media professionals and journalists.

Make It a Conversation

Make it a conversation: That is what Deutsche Welle’s Arabic TV anchor Jaafar Abdul Karim does on his program “Shabab Talk,” where even controversial topics are covered, such as human rights, and topical questions such as “in Saudi Arabia, why are women not allowed to drive?” Abdul Karim takes call-ins, puts listeners on the air regularly, and sometimes goes on location with studio audiences in the Middle East.

Watch video: Interview with Jaafar Abdul Karim.

In September, the journalist wrote a column for the newspaper Die Zeit (September 21, 2015) addressed to the refugees flooding north from Syria, titled “Refugees: You too are now Germany!” He urged them to learn German quickly, and gave this further advice:

Live and let live is a tried-and-true motto in Germany. Please make it your own mantra as well. If you see a couple kissing on the street – even if it is two men or two women – just accept it, even if it is a shock for you. The fact that you’re not used to it doesn’t make it wrong. You are now living in a different system of values – one that you must respect so that all of us here can live peacefully with each other. [71]

Go with Your Strengths

Both the BBC and VOA broadcast news on satellite TV to Iran. Although the satellite dishes required to receive the broadcasts are illegal, an estimated one-third of the population has access to one. Despite what the government says, the U.S. is popular with many Iranians who each day want to know: what is Washington saying about us? During the recent lead up to the nuclear deal with Iran, VOA Persian Farsi-language coverage of the negotiations and the congressional debates is understood to have enjoyed record audiences in the country.

Holland’s Radio Netherlands (RNL) no longer does very much broadcasting. Yet its lively new digital offerings feature topics the Dutch are celebrated for: promoting democracy, the rule of law and openness about sexuality. Radio Netherlands conducts frank conversations about sex on its chat rooms with young people around the world, some of them living secret lives under repressive regimes.

“Every week, people come out as lesbian or gay to us. And then they want to come out more widely. We do counselling: ‘you’re in a country where this is illegal, and you need to be careful,’” says Michele Ernsting, who runs “Love Matters” for Radio Netherlands, with websites aimed at China, Mexico, Kenya, India, Venezuela, Uganda and Egypt. “Love Matters” recently had its hundred millionth page view, across all sites.

“The starting point is Dutch,” she says. “The Dutch have a very non-judgmental approach to sexual health and sexual rights.”

The difference between “Love Matters” and other sexual health sites is something Ernsting calls “the pleasure principle.”

“We see love, sex and relationships as a positive thing in people’s lives,” she says. “This is a big thing in the world of funders, who don’t want us to talk about pleasure – just disease. The most important thing to know about young audiences is that you have to reflect their desires. They can spot a lecture a mile away. They can spot propaganda a mile away. They won’t get near it.” [72]

Music is one of America’s strengths. During the Cold War, Willis Conover’s jazz show on VOA was one of the most powerful exports of American culture, pulling audiences behind the Iron Curtain in the millions to an erudite weekly radio program featuring music and interviews from Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday and many more, for more than 40 years. Today, VOA music broadcasts like “Beyond Category,” a jazz interview and performance show, and “Border Crossings,” which has featured artists like Taylor Swift and Jimmy Cliff, reach substantial audiences on TV, radio and the Internet.

Another American strength is the English language. VOA has been teaching English on the air since 1959, creating a strong loyal audience base. Myanmar President Thein Sein told me he learned his English from listening to VOA “Special English” news broadcasts as a young lieutenant. That may have contributed to his decision to allow VOA “Learning English” programming to air for the first time on Myanmar State Radio. Today VOA mobile apps and daily segments are wildly popular in some markets. An example is Jessica Beinecke’s “OMG Meiyu” which teaches American slang to eager young Chinese.[73] The Ukrainian government and others have recently asked VOA to do much more to teach English to their citizens.

Watch video: Episode of “OMG Meiyu.”

Satire Is Hard but Can Be Powerful

News has the highest ratings on VOA Persian but when it works, there are few programs more powerful than satire. Getting the chemistry right is much harder however than doing a news broadcast. From 2011- 2012, VOA Persian broadcast a comedy show called “Parazit.” Sitting at a desk, in the style of Jon Stewart on “The Daily Show,” host Kambiz Hosseini mocked the Ayatollah and other powerful figures in the Tehran regime, accompanied by music and graphic sequences reminiscent of Monty Python, dreamt up by producer Saman Arbabi. The show was a hit among young Iranians. For a time, black market copies were sold on Tehran streets. But keeping the creative chemistry on track was not easy. “Parazit” collapsed after Hosseini and Arbabi had a falling out.

Watch video: CNN reports on “Parazit.”

Curate and Present the Opinions of Others

State-funded media need to separate news from opinion, if anything, even more rigorously than other media, in order to avoid even the appearance of spin on behalf of government policies. Journalists working for VOA should not write editorials, but there is nothing wrong with curating and presenting the opinion of others, if it is done well and clearly labelled. In early 2015, VOA started a commentary and opinion page on its English language website. The page features brief summaries and links to opinion pieces from American news outlets across the political spectrum, from the National Interest to Mother Jones.

Each day, it highlights varied American opinion on a single issue, such as the Iran nuclear deal or gun control. The page also presents text and video of statements by key U.S. officials that the opinion page editor believes VOA’s international readers may find interesting, or that the administration would like VOA readers to know about. Just as at a traditional newspaper, in other words, there is a place on the opinion page, for the “owners” to have their say – in this case U.S. policymakers. The page helps VOA to better fulfill its 1976 charter, which calls for coverage of American policies and reasonable views on them, along with news of interest to VOA’s audiences. The key here is clear labelling, and separation of the editorial page duties from those of the regular newsroom staff.

What Would Not Work

Some senior officials in the Obama Administration argue that VOA and its sister entities should drastically reduce the number of languages they broadcast in – to perhaps six to eight, including English – and thus increase resources for those key audiences. This would be a mistake. Part of the secret sauce of VOA and its sister U.S. broadcasters is their willingness – unlike some other international broadcasters – to reach out to audiences in their mother tongues, not just colonial ones. Adding Bambara in Mali, for example, clearly extended VOA’s reach well beyond that of French language broadcasts. While there are no official statistics on the number of French speakers in Mali, just 10 percent of Malians spoke French in 2000.[74] The proportion is believed to have further declined since, with Francophones being principally older and male. Because in many parts of the world fewer women and young people speak colonial languages, the move would cut many of them out of the VOA audience.

In addition, focusing more resources on VOA global English, while welcome, would have the effect of putting VOA in more direct competition with CNN and the BBC, which might be seen by some as an unnecessary duplication of Western broadcasting efforts.

VOA and its sister entities are much less effective than they should be, and should be innovating more, especially since the fast changing media landscape continually offers new ways to reach people.

1: Establish a new and innovative Western media effort directed toward the Russian-speaking world.

One option might be to establish an internationally-supported television news channel based in Kyiv, Riga or Vilnius aimed at Russian speakers outside the Russian Federation, but with programming that is attractive to all Russian speakers and that can be segmented and presented in clips on YouTube and similar sites. Private ownership models could be explored. Soap operas and live sports coverage could be included, along with Russian-language news and information programming from European and American broadcasting organizations including VOA. The possibility of beaming TV air across from Narva, Estonia to St. Petersburg, Russia’s second city, could be examined. A key challenge is that some European broadcasters are reluctant to pool resources for this kind of effort, preferring to go it alone.

The joint VOA/Radio Free Europe daily Russian news program “Current Time,” started as a result of the invasion of Crimea, is seen through affiliate stations on 25 stations in nine countries, but is blocked from Russia itself. “Current Time” is a good start, but lacks the budget and affiliate base to be as influential as it needs to become.

2: Provide 24/7 TV in Mandarin and more circumvention of the Great Firewall in China.

VOA’s Weishi, which means “satellite,” has demonstrated there is an audience in China for such a TV satellite news broadcast, but it currently offers only two hours a day of new material in Mandarin, plus half an hour in Tibetan and some Cantonese. Much more should be done. A 24-hour satellite news channel could attract millions more to a reliable source of information that is an alternative to the Chinese party line. Though uplink satellite jamming is technologically possible (and has been employed in the past by the Iranian regime and others), China has never jammed satellites. Uplink jamming is a blunt instrument, taking out dozens of “innocent” signals on a satellite transponder in order to block one or two. It is bad for business and the Chinese state is in the satellite owning and leasing business, making jamming less likely from that quarter.

Also, Internet circumvention investments by the BBG are allowing millions of Chinese and others to reach news and information that would otherwise be denied to them by the Great Firewall. Those techniques that can be shown to increase audience – in fact, not in theory – should receive more robust funding.

3: Expand reach in the Middle East.

The affiliate model, described above as a successful approach for mature markets, should be tried more aggressively in the Arabic speaking world, as well as in Turkey, Kurdish enclaves and other nearby markets. Currently the BBG relies principally on Alhurra, an Arabic-language satellite news channel at VOA’s sister organization, the Middle East Broadcast Network (MBN), which struggles to compete head to head with Al Jazeera Arabic and other Arab news channels. It has a relatively small slice of the audience pie in the crowded Arabic-language satellite television news market – just 2 percent in the last year, for example, in Egypt.[75] Greater effort should be made to find affiliates: stations willing to have American Arabic-speaking reporters and segments appear on their shows, with news about U.S. policy toward the region and life in America.

4. Produce more mobile apps.

The number of people logging onto VOA and other Western media through mobile phones instead of desktop computers is surging. Mobile devices will eventually dominate all other platforms for delivering news and information. Mobile apps in every language, with tailor-made news material are overdue.

5. Public diplomacy needs to be made a priority.

American public diplomacy and U.S. international media both need to be better organized and funded. In my view, the 1999 closure of the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), once headed by Edward R. Murrow, was a mistake. At the State Department, public diplomacy is still treated as less important than traditional diplomacy. In the digital age, that thinking is outdated.

More robust funding is needed to counter message against ISIS recruitment and other hateful propaganda, particularly on social media. The actual online work should not be done by Americans. It should be contracted out to partners in the region.

Writer Jared Cohen argues for a major coordinated effort involving governments, companies and NGOs to “marginalize” ISIS on the Internet. “At first glance,” he says, “ISIS can look hopelessly dominant online, with its persistent army of propaganda peddlers and automated trolls. In fact, however, the group is at a distinct disadvantage when it comes to resources and numbers.” [76]

A full scale digital counterinsurgency campaign, Cohen says “would also make the group’s real-world defeat more imminent.” A robust effort along these lines could be organized, bringing together resources from U.S. national security agencies and from allies – particularly those in the Middle East and North Africa. This is the urgent “gray” part of an information policy that is needed to complement a stronger longer-term U.S. public media effort centered on VOA.

State Department public diplomacy grants should also be made to help local efforts around the world debunk lies and conspiracy theories, along the lines of the Stop Fake website started by a group of journalists in Ukraine, as the Kremlin’s propaganda efforts went into high gear in March 2014.

6: Fix the structural problems at the BBG.

When she was secretary of state, Hillary Clinton argued that the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), the parent organization overseeing VOA and its sister entities, was “practically defunct in terms of its capacity to be able to tell a message around the world.” [77] She was right: it is clear that nine part-time appointees should never have been asked to run a federal agency.

Fortunately, Chairman Jeff Shell and the current board are well aware of the problem. The BBG’s recent appointment of a chief executive officer of U.S. international media is a good first step, but CEO John Lansing needs legislation giving him clear authority over all budgets and personnel so that issues about mission and overlap can be resolved between VOA and its sister entities on the basis of what works best, rather than as shaped by the politics of Congress and a board consisting of four Democrats, four Republicans and the secretary of state. Also, after years of chipping away at it, VOA is no longer a complete media company. It must rely on key support offices that no longer report to the VOA director and are neither properly resourced nor properly organized. VOA needs to be rebuilt so that it can be truly effective.

Should it be the Voice of America, or the voice of the U.S. government? Despite passage of the VOA Charter back in 1976, that debate has never really been settled in some minds, both on Capitol Hill and within the administration. The debate itself has been damaging to VOA’s effectiveness, and it should end.

While I was Director of VOA, a senior State Department official once asked me over to his office for a private conversation, to discuss complaints by a certain government that VOA’s human rights coverage was “excessive.” He said the government in question had earned the right for him to raise their concern since it had been so helpful to the U.S. on national security issues. “Do they offer any evidence of poor journalism,” I asked, “is there anything wrong with the facts, sourcing, or writing?” In response to the request for details came only a repeated general request from the government in question to tone down human rights coverage, with no specifics offered. After quietly verifying the professionalism of the reporting on human rights in that country, I ignored the request entirely.

This is an example of how things should work. The State Department must inevitably collaborate on national security issues with governments that have bad human rights records. But while VOA’s journalism, like that of any serious news organization, must constantly be checked for errors, human rights coverage should never be curbed to please other governments.

Imagine a VOA placed within the State Department. Would it be forced to shape coverage to please helpful but authoritarian governments? Would a media enterprise overseen by the Secretary of State be able to report on a story such as Edward Snowden’s revelations about intrusive U.S. intelligence practices? How about the next Watergate scandal? For that matter, how much credibility and audience would be lost if it was decided that the U.S.-funded media would henceforth put “countering violent extremism” over reporting with balance?

In other countries, government-funded media have faced some of the same questions. At the BBC, Emily Kasriel, head of research says: “Soft power has to be an outcome, not a key driver. Otherwise it can contaminate the journalism.” [78] In Germany, Deutsche Welle’s Director Peter Limbourg says simply: “If you work for a democratic country, you have to play by democratic rules. And it won’t work in a democracy to do propaganda. You won’t be credible.” [79]

In the U.S., the position of the BBG’s new CEO John Lansing is equally clear. At a Senate hearing in November 2015, he said “the credibility of our reporting is our greatest asset. We do not do propaganda.”

There is, however, another key point: good journalism requires more than balance. Certainly, professional reporters must work toward the goals of fairness and objectivity, and an opinion is not normally appropriate except on the editorial page. But the best journalists are not, nor should they ever be, values neutral. In October 2015 remarks, the president of the U.S. Public Diplomacy Council, Adam Clayton Powell III, himself a former executive at CBS News, NPR and other news organizations, put it this way:

To state the obvious, not everything is true; some things are provably false. Not everything is equivalent; some things are repulsive to humanity. Today the choice can be very clear. Seizing neighboring countries’ territory by force is not just another ideology. Shooting down civilian airliners…is not just another point of view. Jailing political opponents in Havana or Caracas is not just an alternative lifestyle. Mass enslavement of women and girls by ISIS is not just another way of exercising power. Mass kidnapping of African boys and forcing them to become soldiers is not just another way to govern. These are, by any objective standard, practices which civilized people everywhere can and do condemn.

“Democracy” concluded Powell, “is not just another ideology, and freedom is not just another point of view.” [80]

Many worry that the U.S. has lost its edge in international communications; that slickly produced television and Internet products from Russia, China, and even ISIS may be having more impact globally than anything this country currently has to offer. It is true that the big budgets of CCTV and RT buy top-flight television producers, flashy sets and great graphics. It is also true that the creators of ISIS recruitment videos and chatroom appeals are highly motivated by ideology and come from the digital media savvy generation. They well understand how to leverage and exploit head-chopping “violence porn” to grab the world’s attention.

But the answer is not to toss out the American tradition of balanced reporting based on universal human values, which has garnered so much respect, and draws many tens of millions to VOA programming each week. Nor is it replacing journalism with propaganda designed to counter violent extremism, however laudable that goal may be. After years of budget cuts, policy drift, and politicking, the answer is to fix the organizational structure at the BBG and put more serious resources into exporting honest journalism

Recent history has shown that putting too much faith in hard power alone does not lead to good outcomes. In the last fifteen years the U.S. has spent over $400 billion developing and operationalizing its F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program. At current budget projections, once complete, the Pentagon will have spent over $1 trillion on 2,457 F-35 jets. For the price of two F-35s a year – just over $200 million – VOA reaches almost 188 million a week with news and information that empowers ordinary people around the world, and builds American credibility. Much more could be done. As a former assistant secretary of defense, says Harvard’s Joseph Nye: “I am all in favor of the defense budget, but we have our proportions all wrong.” [81]

Watch video: Interview with Joseph Nye.

The news will not overthrow Putin, nor cause the Chinese Communist party to allow competitors, nor defeat ISIS, but it can hold all three to global public account. Honest, fair news reporting in key languages is one of the most effective enhancements of its soft power that a democracy can project. In the end, it beats conspiracy theories, spin and hate speech every time.

[1] The author conducted an interview with Dakhil Elias, Voice of America Kurdish Service journalist, on September 14, 2015, via video conference.

[2] Broadcasting Board of Governors, “2015 Performance and Accountability Report,” October 2015. http://www.bbg.gov/wp-content/media/2015/11/BBG-FY2015-PAR.pdf

[3] The full text of H.R. 4490 United States International Communications Reform Act of 2014 can be found on the website of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs: https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/bill/hr-united-states-international-communications-reform-act-2014

[4] The full transcript of the testimony of James K. Glassman, founding executive director of the George W. Bush Institute, to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs Committee’s June 26, 2013 hearing on “The Broadcasting Board of Governors: An Agency Defunct” can be found on the website of the Committee: http://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20130626/101050/HHRG-113-FA00-Wstate-GlassmanJ-20130626.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The author conducted an interview with Peter Pomerantsev, Legatum Institute, on October 7, 2015, via video conference.

[8] Portland Communications, “Soft Power 30,” July 2015, p. 7. http://sp.portlandvault.com/ranking/#2015

[9] Ibid. p. 18.

[10] U.S. Department of State, “Foreign Operations and Related Programs: Budget Amendment Justification, Fiscal Year 2015,” 2015. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/234238.pdf

[11] Voice of America, “Interview with U.S. Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Richard Stengel,” September 25, 2015. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/234238.pdf

[12] Heil, Alan L. Jr., Voice of America: A History, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), p. 57.

[13] Voice of America Charter, Section 3, 1976. http://www.insidevoa.com/p/5728.html

[14] “Foreign Losses,” The Economist, May 2014. http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21599833-sweeping-cuts-have-not-killed-bbc-world-service-steady-neglect-might-foreign-losses

[15] Kofi Annan offered these remarks in a presentation to the United Nations General Assembly in October 1998 while serving as UN Secretary General.

[16] Davies, Caroline, “Aung San Suu Kyi praises BBC World Service,” The Guardian, June 19, 2012. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jun/19/aung-san-suu-kyi-world-service

[17] BBC World Service, “The Economic Return to the U.K. of the BBC’s Global Footprint,” November 2013. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/insidethebbc/howwework/reports/pdf/bbc_report_economic_return_global_footprint_2013.pdf

[18] U.K. Department for Culture, Media and Sport, “An Agreement Between Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport and the British Broadcasting Corporation,” July 2006. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/assets/files/pdf/about/how_we_govern/agreement.pdf

[19] The author conducted an interview with Peter Horrocks, former Director of the BBC World Service on October 15, 2015, via video conference.

[20] Wolf, Martin, “Public Broadcaster Belongs to the People,” Financial Times, October 29, 2015. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2e21620c-7e2d-11e5-a1fe-567b37f80b64.html

[21] U.K. House of Lords Select Committee on Soft Power and the U.K.’s Influence, “Final Report: Persuasion and Power in the Modern World,” 2014. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldsoftpower/150/15004.htm

[22] Author interview with Peter Horrocks.

[23] The author conducted an interview with Vasily Gatov, visiting fellow, USC Annenberg Center for Communication, Leadership and Policy, on October 6, 2015. The interview was conducted in-person and a written transcript was taken.

[24] Koltsova, Olessia, News Media and Power in Russia, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), p. 18.

[25] Dougherty, Jill, “How the Media Became One of Putin’s Most Powerful Weapons,” The Atlantic, April 21. 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/04/how-the-media-became-putins-most-powerful-weapon/391062/

[26] Bessudnov, Alexei, “Media Map, ” Index on Censorship, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2008, p. 184.

[27] Nardelli, Alberto, “Vladimir Putin’s approval rating at record levels,” The Guardian, July 23, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/datablog/2015/jul/23/vladimir-putins-approval-rating-at-record-levels

[28] Author interview with Vasily Gatov.

[29] Luhn, Alec, “MH17: vast majority of Russians believe Ukraine downed plane, poll finds,” The Guardian, July 30, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/30/mh17-vast-majority-russians-believe-ukraine-downed-plane-poll

[30] The author conducted an interview with Peter Pomerantsev, Legatum Institute, on October 7, 2015, via video conference.

[31] Pietiläinen, Jukka, and Dmitry Strovsky, “Why do Russians Support Censorship of the Media?” University of Helsinki, 2010. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/24366