Videos

Digging into crime data to inform news coverage across beats

Reports & Papers

By:

Kyla Fullenwider, Shorenstein Center Entrepreneurship Fellow

Greg Fischer, Mayor of Louisville, Kentucky

Design: Brockett Horne

Research Assistants:

Isabella Borshoff

Kevin Frazier

Our democratic institutions have never been more important or more vulnerable, and the United States Census is no exception. Every decade since 1790, the 228-year-old institution has conducted a count of our nation’s population to determine both congressional apportionment and the annual distribution of federal funding—now over $800 billion every year.1

The census provides our nation’s foundational dataset, the basis upon which so much other data is based. It is used in research, algorithms, journalism, business and infrastructure planning among other things. In many ways it creates the reality upon which our institutions, our lives, and our futures are built. It is the people’s data, a shared public asset that is becoming increasingly important in a data-driven world.

It is in this context that, for the first time in 2020, millions of U.S. residents will use their phones, computers, tablets and laptops at home, from work, or on the bus to respond to the constitutionally mandated survey. And hundreds of thousands of federal workers will use handheld devices to conduct the Decennial count in real time.

Our nation’s first “digital” census presents myriad opportunities for a truly participatory count, but a confluence of issues threatens to undermine its integrity. Political rhetoric is inflamed, disinformation campaigns are an increasing threat, hiring is strained, and an untested question on citizenship has been added to the survey.

As our country gears up to embark on this national modernization effort of enormous consequence—our nation’s largest non-wartime effort—new strategies and tactics are needed to navigate our politically charged, digital world. And these strategies and tactics should be deployed by a broad range of contributors, including leading digital platforms, civil society, media outlets, and local governments.

With trust in federal government and institutions at historic lows,2 local governments, including cities and counties, must play a critical role in the 2020 Census. Cities, in particular, are well positioned to address some of the greatest threats to the Census. Their existing infrastructure, access to trusted messengers in Hard to Count (HTC) communities, and ability to deploy “boots on the ground” through distributed grassroots efforts, allows them to engage citizens in ways the federal government cannot.

Cities will be on the front lines of ensuring a complete count of their constituents. Yet many are not prepared and do not have not enough resources for robust Get Out the Count (GOTC) efforts. This paper, while by no means exhaustive, provides a framework for understanding the challenges ahead and the ways in which cities can uniquely impact their own counts. City leaders understand that an inaccurate census leads to underrepresentation and fewer dollars for many of the most vulnerable populations and communities that need them most. If we don’t get the census right, there is so much we are at risk of getting wrong, the implications of which will last for at least a decade.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.

—ARTICLE 1, SECTION 2

As mandated by Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution, the United States has, since 1790, conducted a census of our population in order to determine Congressional representation. While this concept doesn’t seem revolutionary or even especially innovative today, it was the first of its kind. Censuses had historically been used for taxation, and while paying back its war debts was a chief concern of the cash poor newly united states,3 the Founders also saw in this large-scale collection of data an opportunity to distribute political power among the states.

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Quincy Adams, and Martin Van Buren all worried over “the questions raised by the census and apportionment process were very much on the minds of America’s most distinguished political leaders,” Margo Anderson notes in The American Census: A Social History. In 1787 a fiery debate between states over how to count slaves disrupted the constitutional convention and the progress of the nascent union. It was James Madison’s proposal that moved things forward but ultimately set in motion an expansion of power for slave rich southern states. The complexity of the count was not lost on the architects of the Constitution. Hamilton, Jefferson, and later Daniel Webster would all debate the best mechanisms for apportionment but ultimately understood that there was no perfect way to count everyone.4

Enshrining the census into our Constitution was a shrewd, if imperfect, solution for determining taxation and representation. Practically, it incorporated new people and new states into the still-forming nation and empowered Congress to raise funds to pay back debts. Politically, it created a mechanism for representation and empowerment of all states and their residents, though there were structural imperfections from the start.

But whether these early overseers of the census understood how far-reaching and important census data would become beyond apportionment is unclear. However by the 19th century the consequences of a “good census” were obvious to lawmakers who were paying attention. In 1850, when grossly inaccurate data misrepresented the impact of slavery in the South, policymakers and the public saw the census not just as an apportionment tool, but as a way of understanding who we are as a nation.

Today, the importance of census data is hard to overstate. Not only does it determine congressional apportionment and how over $800 billion dollars in federal funding is spent each year, it also guides infrastructure expenditures for highways, public transportation and the construction of new schools, hospitals, and fire departments, as well as the funding that determines much of our domestic resource distribution, including Medicare, Medicaid, Headstart and WIC.

So what does census data mean to local and state governments? A lot, as it turns out. Let’s take a look at how it plays out in terms of real dollars. In addition to federal dollars, states also use census data to distribute state funding at the county and city levels. How census results inform funding levels varies by program, and no two states, counties, or cities have exactly the same mix of programs or funding mechanisms. Andrew Reamer points out this complexity in “Counting for Dollars: The Role of the Decennial Census in the Geographic Distribution of Federal Funds.” He found that about 300 financial assistance programs created by Congress rely on data derived from the Decennial census to guide distribution of hundreds of billions in funds to states and local areas.

Reamer shows that across five programs—Medicaid among them—the median FY 2015 overall loss per person missed in the 2010 census was $1,091, and in some cases, even larger. A state such as Pennsylvania stands to lose $1,746 dollars for every person missed.5 This means an undercount of one percent could cost the state as much as $221,762,564 in federal dollars every year for the next decade, across a handful of critical program areas.

Let’s look at Kentucky: A new report estimates over $15 billion dollars across just 50 of the federally funded program areas was distributed to the Bluegrass state in FY 2016, and Louisville, which makes up approximately 17 percent of the state’s population, may have as much as $2.5 billion dollars at stake across these program areas.

Four of these programs that exclusively serve children—the Children’s State Health Insurance Program, Title IV-E Foster Care, Title IV-E Adoption Assistance, and the Child Care and Development Fund—all rely on federal reimbursements. At the same time, children aged 0–4 are historically the most undercounted age group, with an estimated net undercount of 4.6 percent in the 2010 census.

Large counties are especially at risk of an undercount of young children, according to research from Bill O’Hare’s “The Undercount of Young Children in the U.S. Decennial Census.” Based on official data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Demographic Analysis operation, O’Hare found that the largest counties in the country had an undercount of children that was much higher than national average (-7.8 percent vs -4.6 percent) and that 77 percent of the net undercount of children occurred in the 128 largest counties.6

Census counts also determine direct funding to cities for resources like Community Development Block Grants (CDBG). In FY 2015 Census Bureau data was used to allocate $1,779,474,572 in CDBG grants across the country.7 From 2011–2018 the City of Houston received a total of $188, 505,187 in HUD funding based on their 2010 census count (an average of over $23 million a year). Many cities that rely on block grants had undercounts in the 2010 Census and it follows that places that are undercounted in the Census do not get their fair share of public funding over the course of the following decade.

But it’s not just money that matters in the census. Though one of the most noted uses of census data is for the purpose of drawing congressional districts, it is also used to draw state legislative districts, school districts and voting precincts. Census data has consequences that can last a lifetime because it is used by policy makers and urban planners to shape the future of our cities’ infrastructure—including schools, parks, highways, public transportation, hospitals, libraries, police and fire departments. Urban quality of life issues that directly impact communities for decades—such as where a new park or school should be built—depend on an accurate count.

The last Decennial Census took place in a vastly different technology and media landscape: Facebook and Twitter were not yet dominant news platforms, WhatsApp and Instagram were nascent, and barely a quarter of the U.S. had smartphones—the Census was still largely submitted through a paper form. Today, a large majority of Americans have smartphones and in 2020 many will submit their personal data through an online census form for the first time in our nation’s history. The Census Bureau is adding and integrating an internet-self-response option (ISR) aiming for approximately half of all respondents. Hundreds of thousands of staffers will use hand-held enumeration smart devices to conduct the count in real time. And while many respondents—especially those considered hard to count—will prefer to answer “offline” using a paper form, these modernization efforts present both opportunities and challenges, including a host of technical vulnerabilities that the Census Bureau is facing for the first time.

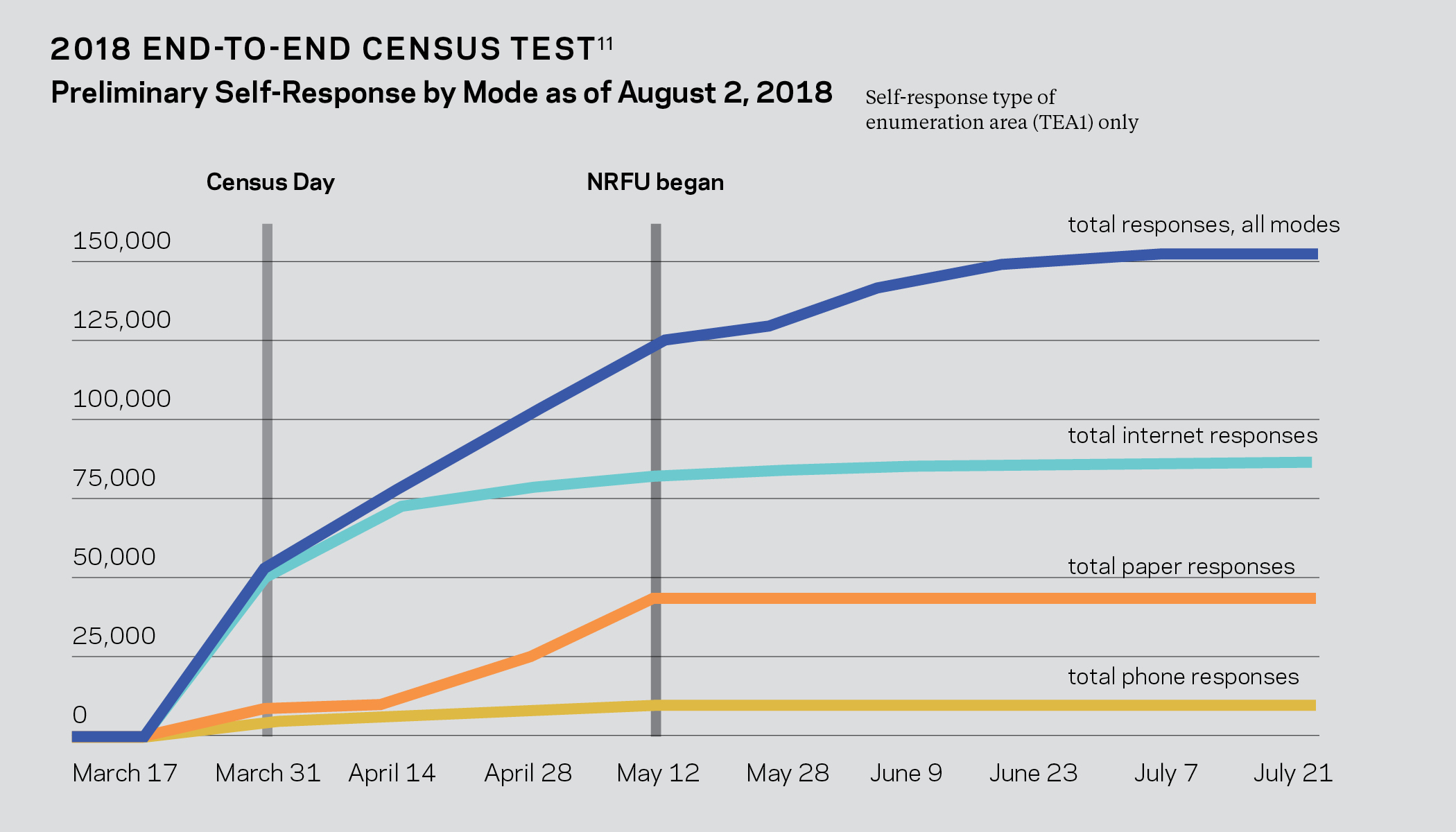

During the 2018 Rhode Island End-to-End test a majority of those who self-responded used the internet-self-response instrument (61.2 percent), followed by the paper form (31.3 percent), and the phone (7.5 percent). Research from advocacy and civil society groups indicates that many people of color prefer to respond using a paper form.12

What often comes to mind when people think of the census is an image of a census worker knocking on a front door, clipboard in hand. It’s an image so ingrained in our cultural imagination that even Saturday Night Live has parodied it. And yet by the time a census enumerator is deployed, there has already been a failure of sorts because a resident has not responded on their own. Sending an enumerator to a household is expensive: In 2010 it cost taxpayers over $2 billion dollars to conduct non-response follow-up for approximately 57 million households.13 And enumerators don’t always yield the best outcomes. After multiple attempts to reach a household are made, enumerators will sometimes identify a proxy to answer questions about the residents of that household. Proxies can be neighbors, landlords, or others who know who resides in a residential unit but may not know the specifics of that household.

In 2020 self-response will be even more important than in previous decades. In 2019 the U.S. Census Bureau conducted focus groups with a number of HTC groups and the results showed a consistent theme: fear of government workers knocking on their doors and coming into their homes. Cities will need to take steps to make it easy to self-respond whether online, over the phone, or through the paper questionnaire for populations who may be hard to count. Even in municipalities such as Louisville, which are known for welcoming immigrants, there will be fear and distrust of government. Self-response will be essential to obtaining the most complete and accurate count, which is why Louisville—and cities across the country—have created Municipal Complete Count Committees to increase self-response, and dedicated resources to focus in part on how to alleviate concerns of immigrant communities.

The Decennial Census has always presented an enormous operational challenge: count everyone, only once, and in the right place. That challenge may be magnified in 2020 by a unique confluence of forces. Alongside the more intractable problem of an increasingly diverse and mobile “hard to count” population, disinformation campaigns, political rhetoric aimed at vulnerable communities, the addition of an untested citizenship question, hiring issues, security threats and the first ever online response option pose additional risks. Let’s take a look at some of these challenges.

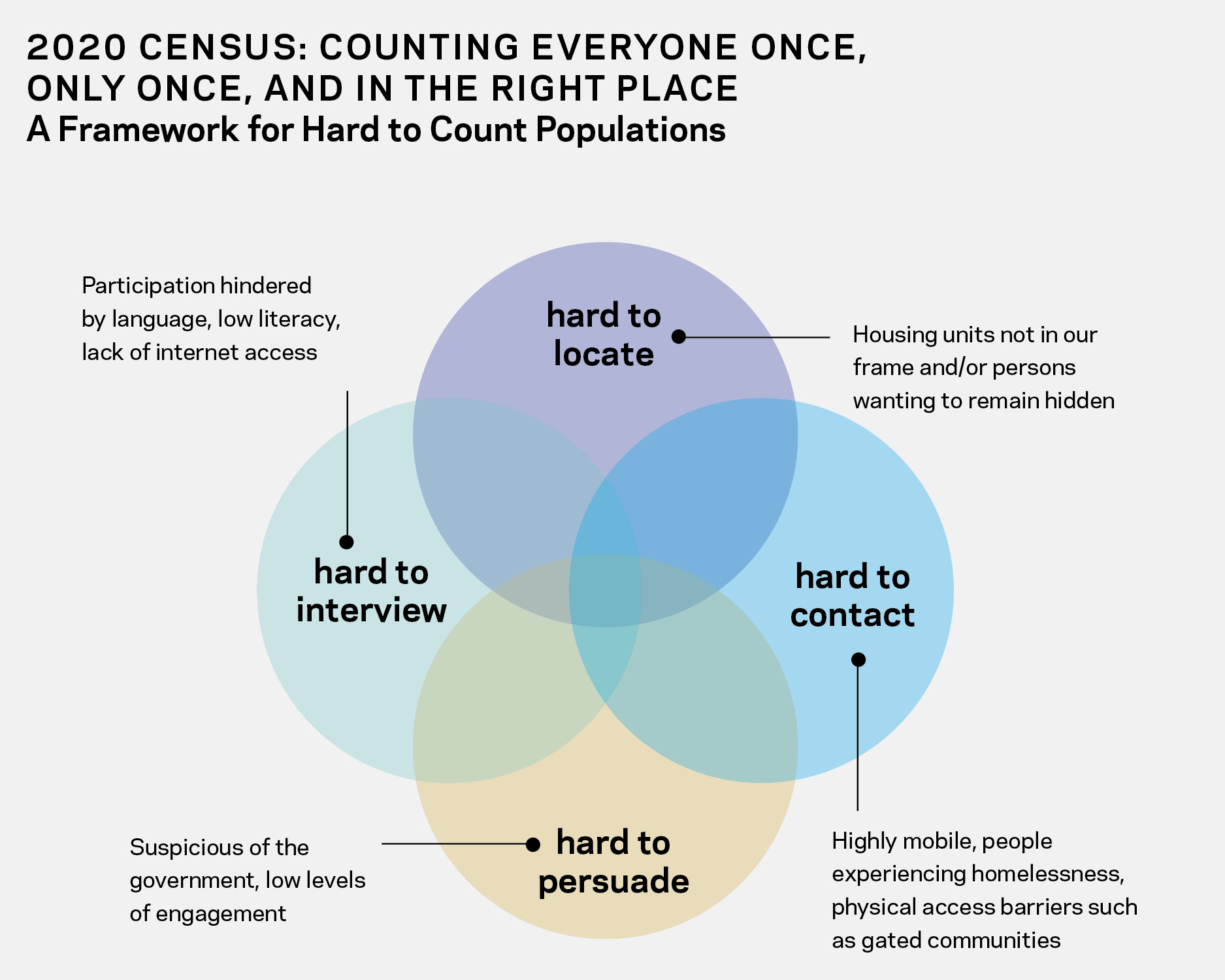

Any count of the nation’s population is bound to have some degree of inaccuracy. This can mean some individuals (for example, those who have a second home) are over counted, while others (such as renters) are undercounted. In 2010, for example, Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Natives were undercounted while the non- Hispanic White population was over counted.14 Populations are deemed Hard to Count (HTC) for a variety of reasons that make them hard to identify, hard to contact, hard to persuade or hard to interview. The HTC population generally lingers around 20 percent of the population, depending on the region, but those rates could increase significantly in 2020.

Since 2010, the Census Behaviors, Attitudes and Motivators Survey (CBAMS) has studied and described what motivates or prevents people from participating in the census. These barriers and motivations are important to understand and can inform local GOTC efforts. Motivations include understanding the impact the census has on funding community resources, and hearing from trusted messengers who validate the importance and safety of the census. Common barriers to participation include distrust in government, data privacy and confidentiality concerns, fear of repercussions, and generalized apathy.15

The Census Bureau has, over the years, made significant efforts in reaching HTC populations, including investing heavily in local outreach efforts. And while the 2020 Census will receive an increase in funding from 2010 levels for their advertising campaign there are critical program areas that will see significant funding cuts. In 2010, millions of dollars of in-kind partner support for campaign materials and other resources were allocated to over 30,000 Community Based Organizations in some of the hardest to count regions across the country. While the program was challenging to manage, it was in many cases the only form of financial assistance these organizations received to engage their communities. The program will not be funded in 2020.

A relied-upon method of reaching HTC populations is the Census Bureau’s Community Partnership and Engagement Program (CPEP). This program area is tasked with reducing the differential undercount by forming partnerships with trusted community messengers and organizations such as churches, community groups, and libraries, and has received significant investment from the Bureau. Still, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the Census Bureau is shrinking its partnerships staff in 2020 by eliminating the hyper-local Partnership Assistant position.16

These positions—approximately 1750 “boots on the ground” in some of the hardest to count communities—will not be hired in 2020 because Recovery Act funding (about $125 million in 2017 dollars) used to make these hires will not be allocated in 2020. Fluent in over 100 languages, Partnership Assistants distributed messaging, provided early education to at-risk communities, and attended community events among other things. The program staff’s diversity was a significant factor in allowing the 2010 campaign to reach at least 99.8 percent of all adults in the U.S., including 99.3 percent who were reached in their native language.17 Cities with diverse HTC populations, especially those that are not bilingual, could be especially vulnerable to an undercount.

Because HTC populations are less likely to self-respond, reaching them requires hiring enough enumerators to conduct the Non-Response Follow Up (NRFU) operation in person. That was a difficult task in 2010, a period of high unemployment, and will be even more difficult in a period of low unemployment. This challenge is further aggravated by the fact that only citizens will be allowed to work as Census enumerators in 2020. Although the federal government generally prohibits non-citizens to work for the government, the Census Bureau has previously received waivers from the Office of Personnel Management to allow it.18 Not so this time. Consequently, cities and regions with low unemployment rates and higher than average HTC populations could face a higher risk of being undercounted.

An omnibus spending bill under consideration as of this writing directs the Census Bureau to deploy a level of effort for partnership and communications efforts similar to 2010; however, it’s unclear if that is feasible unless funds are made available by Congress and the bureau can move quickly to hire in the areas most at risk of an undercount. Even then, the Census Bureau is hamstrung by federal hiring constraints that make hiring and onboarding a cumbersome and time-consuming process.

Beginning with the early debates between James Madison and Alexander Hamilton on how to count slaves and Native Americans, who counts in a census is inherently a politically charged question. The Trump Administration’s 2018 addition of an untested question asking about the American citizenship status of respondents is unprecedented and adds to the politicization of the count.

The Census undergoes rigorous testing for years before it’s actually deployed in the field to avoid unintended consequences that can costs taxpayers billions of dollars and have decades-long impacts. The citizenship question was not included as part of the final critical census dress rehearsal in Providence, Rhode Island in 2018. While the exact impact on response rates is unclear, the Census Bureau and former directors have warned that the addition of a citizenship question will “inevitably jeopardize the overall accuracy of the population count.”19 Furthermore, in early 2019, a Federal judge ruled that adding this question was “unlawful” and “arbitrary” and blocked the Trump Administration from including the question. But it’s unlikely to end there. As of this writing, the Trump Administration has appealed the ruling and the Supreme Court has agreed to hear the case in April of 2019.20

Regardless of where this question lands legally, fear and misunderstanding of how census data can be used is pervasive in many immigrant communities. Nationally, nearly one in ten households have at least one non-citizen and there are over 10 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. (down from over 12 million in 2007).21 Immigrants, in particular, often live in mixed status households meaning citizens, authorized immigrants, and unauthorized immigrants are all under the same roof.22 As a result, entire households, not just the undocumented members, could go uncounted. This multiplier effect on response rates in these communities means that for a city with even a small immigrant population undercounts of entire households could result in a significant undercount of the city as a whole.

While much of what exacerbates fear in immigrant populations and communities of color is real, some of that fear is stoked intentionally through the spread of disinformation. Emerging research shows that information around the census is likely to be manipulated in much the same way as information around the 2016 elections in order to depress response rates among certain populations. Misinformation has always been around to some extent but its amplification and rapid diffusion across social media platforms and closed messaging services makes it an especially difficult challenge today.

A municipality’s social media channels will be at the center of these activities and, if not properly fortified, could be easily manipulated. A 2017 Shorenstein Center Report “Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making” defines several ways in which information is manipulated and corrupted.23 For the purposes of this discussion, we will focus on two of these definitions that are important for understanding some of the specific types of threats to the census:

Stopping a rumor on a community Facebook page is easier than halting an endless disinformation assault. Still, regardless of intent, census misinformation and disinformation undermine trust and exacerbate fear and skepticism. Cities will need to take both preventative measures to address the spread of misinformation and prepare crisis communications strategies to address harmful disinformation campaigns aimed at stoking fear and depressing response rates.

On August 31, 1954, Title 13 was passed in the U.S. Congress to ensure the private data that Americans enter on their census form is confidential. Title 13 provides one of the strongest protections in the United States Code for information the Census Bureau collects from individuals and businesses. These protections include:

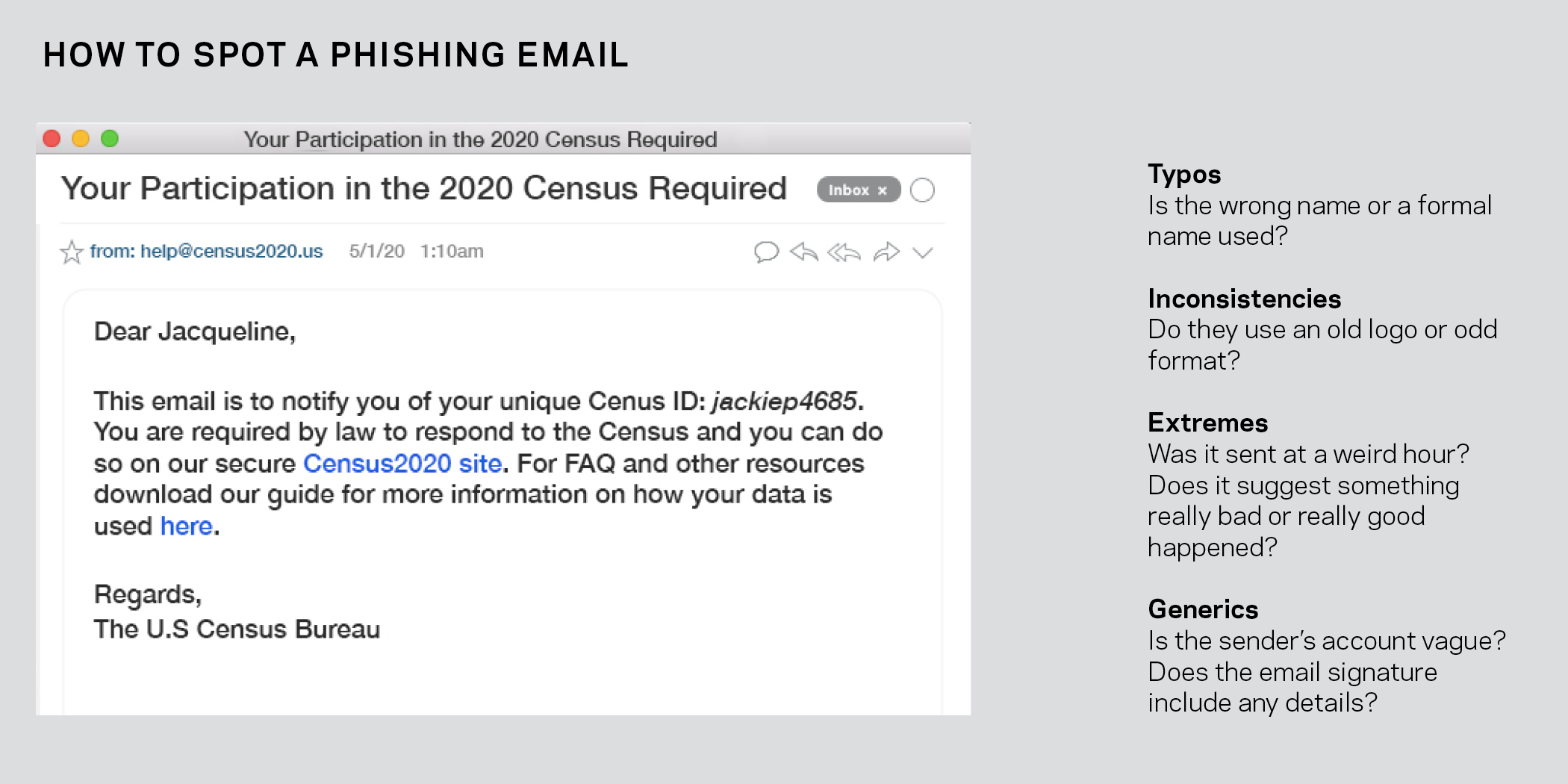

Title 13 provides meaningful and substantive protections for citizens concerned about the federal government misusing their data—any changes to this law would need Congressional approval. Yet while federal law prohibits the Census Bureau from sharing individual data (including with other federal agencies such as the FBI and ICE), phishing schemes, data breaches, fake phone numbers, DDoS attacks, and misleading videos and other media perpetrated by both state and non-state actors have the potential to cause real harm. And though cities are limited in their capacity to address many of these threats, they can take meaningful actions to mitigate phishing and other misleading outreach by creating public awareness, including what to look for, how to respond, and when to report.

Recent Census Bureau research shows that communities with low internet connectivity and digital literacy are vulnerable to an undercount. Cities with digital deserts will need to be especially diligent in providing access, information and resources about how to submit the census online or in paper form, and early education about how to avoid common security concerns like phishing.

Paper forms will be sent in the first mailing to regions with known broadband issues or high concentrations of households unlikely to use the internet (about 20 percent of the country). But cities with low broadband subscription rates and low digital literacy will need to fortify their digital infrastructure with a range of interventions, resources and education.

Determining which cities are the most “at risk” is challenging because of the operational complexity of the Census and the diversity of HTC populations. However, there are some things we know matter, based in part on emerging research conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2018. Cities most at risk of an undercount will likely have some combination of the following characteristics and those with a number of these characteristics are at a particularly high risk of being undercounted.

In addition to the consistent characteristics of HTC populations, the Census Bureau has identified specific demographic groups that will require even greater outreach to encourage census participation in 2020. These include:

The challenges described thus far—an increasingly hard to count population, the addition of an untested citizenship question, disinformation campaigns, staffing, security and the deployment of the first online form—are daunting. And while the U.S. Census Bureau will have resources devoted to addressing these concerns, the significant distrust in federal government across broad swaths of the population means that there are a lot of things the federal government can’t do. That is, many of the most effective ways of getting out the count need to happen at the local level. Let’s take a look at local assets and how they can be leveraged for a successful GOTC effort.

Trust matters enormously, particularly among communities and populations that are fearful of how their data can be used and are distrustful of federal government. A 2017 PEW Trust in Government Study found that only 18 percent of Americans say they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (3 percent) or “most of the time” (15 percent).24 However, most Americans trust their local governments and institutions: Although only 35 percent have a favorable opinion of federal government, 67 percent have a favorable opinion of their local government.

A similar dynamic plays out with the media. Americans are much more trusting of both local newspapers and television than national outlets.25 However, some civil society organizations have conducted research showing that the hardest to count populations will remain skeptical of messages coming from media and local government. And so while there is no silver bullet for building trust, city officials working in collaboration with local and ethnic media outlets can help normalize the census, build trust, and combat the spread of disinformation.

Cities have hundreds of local touchpoints with citizens. Bus shelters, utility bills, taxi screens and libraries are just some of the communication vehicles that can all be leveraged for GOTC efforts. Mapping all the touchpoints across a city and integrating a communications strategy that leverages those touchpoints can create a “surround sound’ effect in the lead up to 2020. Cities with low internet proficiency and access can provide public access through things like Census Kiosks, mobile vans with internet, and Census Wi-Fi hotspots and charging stations.

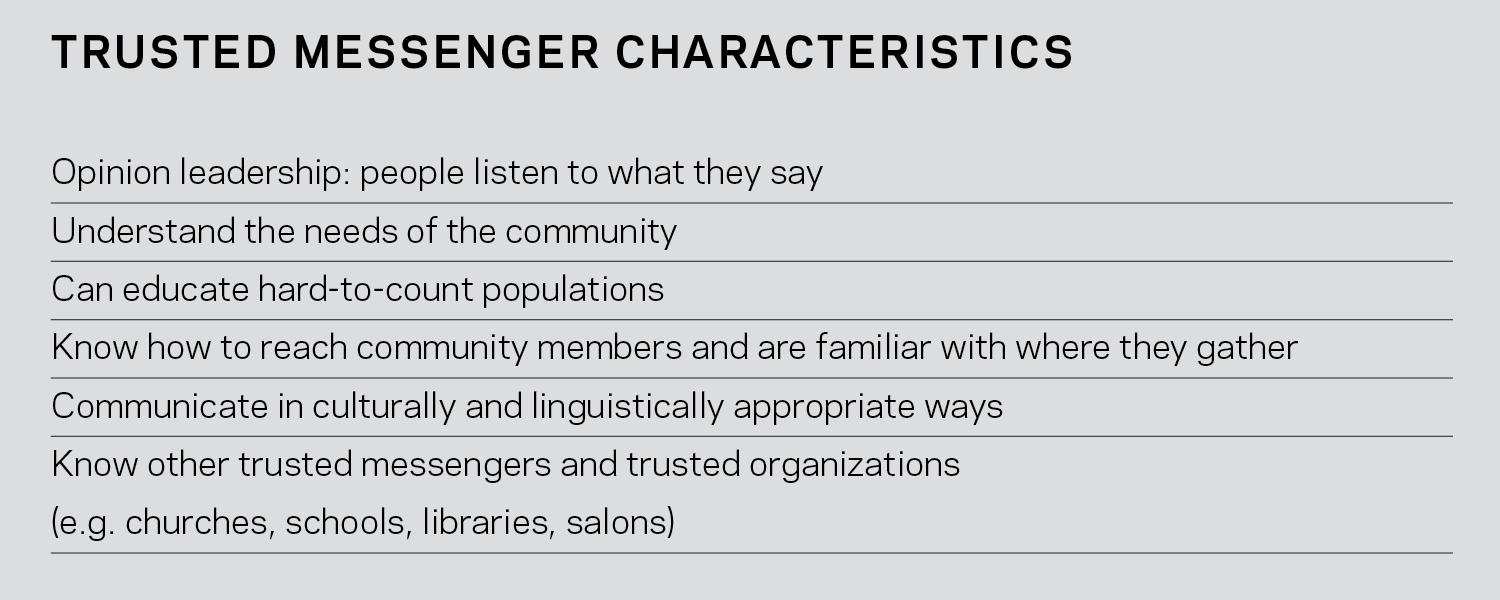

For some of the hardest to count communities, access will not be enough. Individuals and communities fearful of the government will need to hear from people they trust that the census is safe. Trusted messengers are highly respected individuals in a community who influence others on important matters, and if engaged as “early adopters,” they are an essential and critical component of any GOTC effort.

In his 1962 book “Diffusions of Innovations,” Everett Rogers identifies what he calls “early adopters” as one of, if not the most important factor, in whether or not something is adopted.26

“Early Adopters have the highest degree of opinion leadership in most systems. …

The early adopter is considered by many to be the individual to check in with.”

What Rogers points to is at the heart of what trusted messengers do in a HTC community: They take away the risk and alleviate fear. Faith leaders, social service workers, teachers, doctors and librarians can all be trusted messengers. But there are often trusted messengers in less obvious places, such as salons and barber shops, churches, coffee shops and other community hubs who have vast networks of influence. Cities can cultivate and build a network of trusted messengers who are equipped to talk about why the census matters, address fears and concerns, and respond quickly in the case of a crisis.

Recent Census Bureau research shows that one of the most effective ways of increasing participation in the census is to show the value it brings to local communities. Respondents who participated in the Census Barriers, Attitudes, and Motivators Survey (CBAMS) indicated that understanding the impact census has on their local community makes them more likely to participate. Cities are well positioned to show the value that federal funding brings to the things that community members use or rely on every day, such as schools and fire departments. Mayors can bring a policy perspective by showing how policy goals like addressing chronic homelessness are directly impacted by an accurate count.

Different HTC populations may require different outreach tactics, and cities may have

areas of critical need that are specific to their municipality. For example, Los Angeles will need different outreach methods for different populations, ranging from Cambodians who are fearful of such counts, to young Millennials who have never participated in a census and may not feel it matters, to people experiencing homelessness. Some of these groups may require longer and more costly engagement than others. And because municipal resources are often stretched, prioritizing GOTC efforts around critical funding gaps and the populations most impacted by those gaps can help a city focus limited resources for their GOTC efforts.

Finally, characteristics that are idiosyncratic to a particular region will need to be considered as part of a local GOTC strategy. Some of these factors, such as fragile internet infrastructure, natural disasters, and an historical undercount of a particular population, place certain populations and geographies at a higher of risk of an undercount. For example, hurricane season begins in Florida just as enumerators begin to knock on doors, which makes self-response an even more critical issue in that region. These variables should also be included and prioritized as the GOTC plan is formed.

In a world where what counts as truth is increasingly up for debate, census data has never been more important. These data are the foundation of understanding what is true and what is false, what is real and what is fake. They tell us where our country is headed and who we are as a nation. And like so many of our most important public goods, census data belongs to everyone and it’s up to us all to protect it.

Our publicly owned institutions—libraries and park systems among them—rely on federal and local government, journalists, individuals, and civil society to safeguard them. The census is no different. Protecting the Decennial—our nation’s foundational public data—will require an all-hands-on-deck effort in the lead up to 2020. The span of federal government, the resources of local governments, the networks of civil society, as well as the agility of the private sector will all be critical to ensuring a complete and accurate count.

Congress must prioritize addressing the obstacles and uncertainty that are threatening to undermine the 2020 Census including the addition of an untested question on citizenship status. This change from 2010 threatens to undermine the integrity of the census by depressing response rates among already marginalized HTC populations, placing states and cities with a disproportionate amounts of HTC populations at risk of an undercount. And to the extent possible, Congress should further strengthen Title 13—essential for protecting data privacy and ensuring participation among the population more broadly.

State and local governments will need to step up too. States can start by identifying the regions most at risk of an undercount and earmarking funds for those areas deemed hardest to count. Both states and counties have a critical role to play in ensuring Complete Count Committees are formed and properly resourced. (About 40 states currently have one). This may mean dedicating resources to oversee census efforts and providing support to the mostly volunteer-led organizations.

Cities, as outlined in this paper, will need to organize and deploy robust and responsive GOTC efforts starting in 2019. State, county, and city governments working together will have the best shot at a complete and accurate count.

As we saw happen in the 2018 midterms, individuals, media outlets, civil society and the private sector will need to work together to increase civic participation and trust in the Decennial. As the political and legal context changes in real time, civil society groups will need to respond in real time: deploying rapid communication responses to keep constituents informed of changes that may impact their communities.

As misinformation and disinformation accelerate across social media and news outlets, local journalists and ethnic media in particular must stay ahead of the news and provide trusted information and trusted sources to their readers and viewers. Digital platforms should start preparing now for the spread of misinformation and disinformation about the census across their platforms.

The private sector will be called upon as well. Companies that rely on census data understand its vital importance and should make census participation a priority for their employees. At a minimum, companies can and should use their platforms to encourage participation in this once-a-decade civic exercise.

As our country continues to grapple with polarizing division, the census is a chance for everyone to be counted. It is a rare, non-partisan opportunity to understand who we are and where we are headed as a nation. And it is an exercise that our republic has, every decade since 1790, managed to see through regardless of partisan threats. Some things are too important to politicize. The future of our data and our democracy depends on it.

Australia’s first digital census is remembered by its own hashtag, #censusfail. At the forefront of public memory are the cyberattacks that brought down the census website, causing mass inconvenience and compromising participation in the survey.27 However, even in the lead up to census day, confusing changes to data retention laws were already undermining public confidence in the census and drawing attention to potential vulnerabilities in the system.

In 2015, the head of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) announced the organization would be changing a decades-old policy of destroying all personal data after 18 months and instituting indefinite data retention. He later clarified that personal data would be destroyed after four years but unique identifiers derived from this data would be kept indefinitely. To the layman, the difference was difficult to discern, and from widespread data privacy concern sprung a movement to boycott the census, which rapidly won over some prominent adherents.

The government unsuccessfully tried to reframe the debate by emphasizing the security of technology systems—which not only turned out to be erroneous but failed to address underlying public concerns about data retention. Reflecting on the event, the ABS chief statistician recognized the need for pre-prepared “crisis communications” to reassure people in the event of a cyberattack or system failure. An even more important lesson, however, is the need for effective and early communication with the public about what their data will and won’t be used for. Confidence in data collection systems mitigates the risk of snowballing mistrust and bad publicity of the sort that plagued the 2016 census, and likely played a role in attracting malicious actors to take down the system on census day.

In 2008 Get Out the Vote campaigners called eligible voters and helped them form a plan for when and how they would vote. Simple questions like ‘What time will you vote?’, ‘Where will you be coming from?’ and ‘What will you be doing beforehand?’ boosted turnout by 4.1%. This increase bumped up to 9.1% in houses with only one eligible voter.28 Get Out the Count strategies can leverage similar behavioral insights and tactics by asking constituents to make a pledge or commitment to respond to the Census.

Combating Distrust in Government and the Value of Trusted Messengers

California’s expansion of state Medicaid eligibility had game-changing potential for the Latino community. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) paved the way for California state legislators to extend Medicaid coverage to those with household incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level. Of the remaining uninsured in California, more than 60 percent were Latino.29

But expanding eligibility was only half the battle. Increasing coverage was another question entirely—and the new legislation did not include state funding for an outreach or enrollment campaign. Many Californians were simply unaware that they were eligible, and a significant proportion of this group belonged to typically hard-to-reach populations.

Yet, by the end of 2017, the number of Californians enrolled in Medicaid had increased by an estimated 4.4 million over pre-ACA levels. What’s more, the uninsured rate for Latinos plummeted from 43.2% in 2010 to 24.8% in 2016. So how did California defy the odds?

The California Endowment, a non-profit health foundation, contracted Mercury Public Affairs to lead an evidence-based outreach program targeting hard-to-reach, uninsured Californians. Acknowledging this group’s prevailing distrust of government and fear of repercussions by immigration authorities, the team recognized community messengers would be integral to any outreach effort. Early polling revealed medical professionals, Spanish news journalists and promotoras (community health workers) were the most trusted messengers in Latino communities.

Preliminary Steps

Ninety-two percent of California’s uninsured but eligible population lived in just 13 counties, so the project team focused their efforts on these regions. They began running standalone health resource fairs across the state, educating attendees about upcoming changes in the health law, local services and screening people for health coverage eligibility. They recruited assisters from inside the most affected communities, checking in with county offices, asking which organizations they partnered with on Medicaid issues, and drawing on these organizations and their partners for staff wherever possible.

Simultaneously, the project team was strategizing around how Spanish media players could be best mobilized as trusted messengers. They brought together a round-table of influential Latino community members, including media representatives from La Opinion, a Spanish-language daily newspaper in California; Univision and Telemundo, the two largest Spanish-language television networks in the state. Univision agreed to a trial partnership with The Endowment to promote a health fair in Fresno. Ten-thousand people showed up.

Asegúrate /Get Covered Campaign

The Endowment went on to launch a formal partnership with Spanish media outlets and state government, known as Asegúrate/Get Covered, with the aim of enrolling two million newly eligible Californians. The Endowment conducted weekly calls with its media partners to provide new insights into effective messaging and ensure consistency between organizations.

Each week, Univision featured four national news segments and five digital pieces on healthcare enrollment. In 2014, it placed 9765 TV advertisements, ran dozens of episodes on healthcare programs, conducted two town halls and produced a mini-documentary.

The Endowment also worked with CBS radio, Power 106 in Los Angeles, La Opinion, Telemundo, and dozens of other outlets. It identified top individual trusted messengers, such as Christina Saralegui (the “Oprah” of Spanish TV), with whom it worked on robocalls and social media ads, and Dra. Aliza, who runs a Spanish-language version of WebMD, which was also leveraged to promote outreach events.

Astoundingly, the campaign hit its target within the first year of enrollments. By March 2015, more than 3 million had enrolled, and that number jumped to a phenomenal 4.1 million 12 months later.

A survey of Latinos conducted in 2013 and 2014 showed knowledge about Obamacare increasing from four percent to 26 percent over this period. Between May and July 2013 alone, the number of Latino respondents who claimed exposure to Obamacare information on Univision jumped from 66 to 80 percent.

Identify Trusted Messengers

Latino communities are often considered ‘hard-to-reach’ because of pervasive mistrust of government officials. Eligible citizens who live in households with mixed immigration status are often wary of applying for benefits out of fear their personal information might be shared with immigration authorities. Non-government messengers like media personalities or trusted ethnic news sources can help dispel these fears.

Be Agile

One of the key drivers of the campaign’s success was its responsiveness to new information. For example, Latino enrollment remained puzzlingly low towards the end of the first enrollment period. The team immediately put a new survey in the field to test the kinds of messages the campaign was using. Counter to their instincts, polling showed more effective messaging emphasized compliance: healthcare was the law, families would be fined if they didn’t have insurance, and there was a hard deadline. Sharing the findings with media partners during weekly teleconferences and doubling down on new messaging made all the difference.

Definition: Complete Count Committees (CCC) are bodies of community and government officials tasked with coordinating their area’s preparation for the census.

1. Identify Hard-to-Count Communities

The City of Baltimore mapped the 2010 Census response rate by neighborhood to identify which communities will likely require more engagement before the 2020 enumeration. Do the same for your community. Then determine target goals and identify trusted messengers for increased participation in those communities.

2. Assess City Resources

Baltimore created a City Hall Census Work Group to guide its CCC and incorporate city staff and resources into the CCC planning and outreach process. Once you know what staff and resources are at your disposal, you will be have a better picture of what’s needed from the community to make your CCC maximally impactful.

3. Partner with Trusted Messengers and Community Stakeholders

To reach its goals and HTC communities, Baltimore recruited leaders in human services, civic engagement, the business community, education sector, faith community, and ethnicity-based organizations. Use your goals, HTC map, and community knowledge to bring a robust range of community stakeholders and trusted messengers into your CCC.

4. Use Expertise to Your Advantage: Form Sub-Committees.

The CCC in Baltimore will be divided into several sub-committees tasked with developing specific strategies for counting communities for which they have the most familiarity and connections. You can empower your CCC volunteers in the same way: encourage CCC members to join and create sub-committees that can then pursue strategies tailored to the residents they know best.

5. Create a Get Out the Count Timeline

An explicit GOTC timeline guides the Baltimore CCC’s work plan. This schedule will help motivate the entire CCC and its sub-committees to take action and work toward the next major deadline. Ensure your own CCC is aware of the time-sensitivity of its efforts and empower them to meet their expectations in a timely way.

6. Introduce Your CCC to Your City

The City of Baltimore held a Census Community Congress kickoff event that brought city leaders and representatives from various sectors together to discuss the CCC’s agenda, opportunities to get involved, and the importance of a complete count to the City. Host a similar event, issue a press release, and leverage your social media platforms to create engagement around the census and your CCC.

1. Andrew Reamer, Counting for Dollars: The Role of the Decennial Census in the Geographic Distribution of Federal Funds (GW Institute of Public Policy, March 19, 2018), https://gwipp.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs2181/f/downloads/GWIPP%20Reamer%20Fiscal%20Impacts%20of%20Census%20Undercount%20on%20FMAP-based%20Programs%2003-19-18.pdf.

2. “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2017,” PEW Research Center, December 14, 2017, http://www.people-press.org/2017/12/14/public-trust-in-government-1958-2017/.

3. Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States, (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 2018), 121, 126.

4. Margo Anderson, The American Census: A Social History, (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1988), 13, 32.

5. Andrew Reamer, Counting for Dollars: The Role of the Decennial Census in the Geographic Distribution of Federal Funds (GW Institute of Public Policy, March 19, 2018), https://gwipp.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs2181/f/downloads/GWIPP%20Reamer%20Fiscal%20Impacts%20of%20Census%20Undercount%20on%20FMAP-based%20Programs%2003-19-18.pdf.

6. William O’Hare, The Undercount of Young Children in the U.S. Decennial Census (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

7. “Community Planning and Development Program Formula Allocations for FY 2018,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/about/budget/budget18.

8. “2010 Census Coverage Measurement Person Results for Memphis City, TN,” U.S Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/coverage_measurement/pdfs/tennessee/plc4748000.pdf.

9. “2010 Census Coverage Measurement Person Results for Louisville/Jefferson County, KY,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/coverage_measurement/pdfs/tennessee/plc4748000.pdf.

10. “2020 Program Management Review,” U.S. Census Bureau, October 19, 2018, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/pmr-materials/10-19-2018/pmr-2020-slides-2018-10-19.pdf.

11. “2018 End to End Test Update,” U.S. Census Bureau Decennial Census Management Division, July 1, 2018, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/pmr-materials/08-03-2018/pmr-update-testing-08-03-2018.pdf.

12. “FCI Briefing Series: Census 2020 Messaging Testing Results,” Funders’ Committee for Civic Participation, September 6, 2018, https://funderscommittee.org/resource/recording-slides-fci-briefing-series-census-2020-messaging-testing-results/.

13. “2010 Census Nonresponse Followup Operations Assessment,” April 30, 2012, https://www.census.gov/2010census/pdf/2010_Census_NRFU_Operations_Assessment.pdf.

14. Nancy Bates, Hard to Survey Populations, ed. Roger Tourangeau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 3.

15. “2020 Census Barriers, Attitudes, and Motivators Study,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/2020-census/research-testing/communications-research/2020_cbams.html.

16. “Report to Congressional Requesters: 2020 Census Actions Needed to Address Challenges to Enumerating Hard to Count Groups,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, July 2018, https://www.gao.gov/produc.ts/GAO-18-599.

17. “U.S. Census Bureau Responds to National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic and Other Populations Recommendations,” October 2016, https://www2.census.gov/cac/nac/reports/2016-10-responses-admin_internet-wg.pdf.

18. Tara Bahrampour, “Non-citizens won’t be hired as census-takers in 2020, staff is told,” The Washington Post, January 30, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/non-citizens-wont-be-hired-as-census-takers-in-2020-staff-is-told/2018/01/30/b327c8d8-05ee-11e8-94e8-e8b8600ade23_story.html?utm_term=.1a0932346ec9.

19. Michael Wines, “Cities and States Mount Court Challenge to Census Questions on Citizenship,” The New York Times, April 3, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/us/census-citizenship-question-court-challenge.html.

20. Michal Wines, “Court Blocks Trump Administration From Asking About Citizenship in Census,” The New York Times, January 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/15/us/census-citizenship-question.html.

21. “Unauthorized immigrant population trends for states, birth countries and regions,” PEW Research Center, November 27, 2018, http://www.pewhispanic.org/interactives/unauthorized-trends/.

22. Jeffrey S. Passel & D’Vera Cohn, “A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States,” PEW Hispanic Center, April 14, 2009, http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/reports/107.pdf.

23. Claire Wardle & Hossein Derakhshan, “Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking,” The Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, October 31, 2017, https://shorensteincenter.org/information-disorder-framework-for-research-and-policymaking/.

24. “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2017,” PEW Research Center, December 14, 2017, http://www.people-press.org/2017/12/14/public-trust-in-government-1958-2017/.

25. Indira A.R. Lakshmanan, “Finally some good news: Trust in news is up, especially for local media,” Poynter, August 22, 2018, http://www.people-press.org/2018/04/26/the-public-the-political-system-and-american-democracy/.

26. Everett Rogers, Diffusions of Innovations, (New York: Free Press, 1962), 283.

27. “Australian census attacked by hackers”. BBC, August 16, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-37008173.

28. David Nickerson & Todd Rogers. Do You Have a Voting Plan? Implementation Intentions, Voter Turnout, and Organic Plan Making, Psychological Science, 2010, 194–9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43348201_Do_You_Have_a_Voting_Plan_Implementation_Intentions_Voter_Turnout_and_Organic_Plan_Making.

29. “Medi-Cal Statistical Brief: Medi-Cal’s Optional Adult ACA Expansion Population”. California Department of Healthcare Services, March 2017, https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/statistics/Documents/Expansion_Adults_201610_ADA.pdf.

Thank you to the following people who helped make this paper possible: Tracy Arnold, Katie Dailinger, Ditas Katague, Terri Ann Lowenthal, Jeff Meisel, Nicco Mele, William O’Hare, Richard Parker, Tom Patterson, Andrew Reamer, Liz Schwartz, John Thompson, and Setti Warren. Special thanks to Brockett Horne for designing the PDF version of this paper.

Videos

Commentary

Videos