Yochai Benkler: The Right-Wing Media Ecosystem

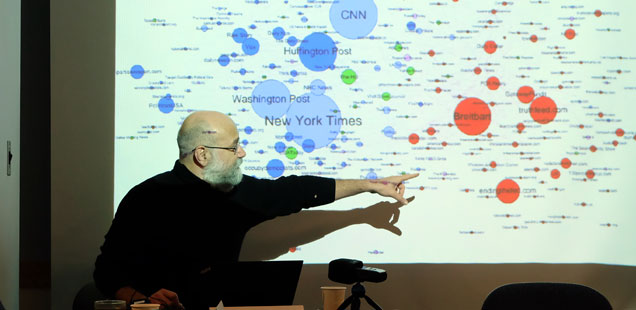

April 5, 2017—Yochai Benkler, professor at Harvard Law School and co-director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard, discussed his recent study on conservative media and the 2016 election, which analyzed more than 1.25 million stories published online between April 1, 2015 and Election Day, 2016. Below are some highlights from the conversation, as well as the audio recording.

Download the presentation slides.

A network with significant influence

“Breitbart was not alone but was enmeshed in a network of sites [such as Infowars and The Daily Caller]…these are the central nodes in the propaganda network that was the foundation of the rise of Donald Trump. It was directed not only to capture the White House, but first and foremost to capture the Republican Party.”

“This is not just [of] historical interest, this network is now ready and jumps up to support the President’s message…they are all working together and they are then amplified and replicated by Fox News, which is the outlet that ultimately captures, as we know from the Pew study, 40 percent of Trump voters.”

The new right-wing media

“Other than Rush Limbaugh….almost nothing here existed before Fox was created in 1996. None of this existed when Ronald Reagan was elected, none of this existed when Bill Clinton was elected, it’s all brand new. It starts with AM talk radio after the Fairness Doctrine was repealed in ‘85, moves on in ‘96 when cable comes to enough households that the market strategy of aiming narrowly to a politically committed audience becomes viable. Then most of what we’re seeing here, other than Breitbart, which is in 2007, emerges after Obama as the foundation of the Tea Party.”

Asymmetrical polarization

The asymmetry strongly suggests that we’re not looking at a technologically determined phenomenon, but rather at a politically, culturally, socially driven phenomenon…

“There is a left mirror, as it were, but it was largely created in 2002 through 2008. Netroots is the source of much of the excitement about the possibility of progressive online organizing, and it is much more tightly linked—and this is the critical point—to the traditional mainstream sources that were there in 1980 when Walter Cronkite was still signing out.”

“What you see is a distinctly asymmetric model of polarization. In the debates over both polarization in Congress and over media polarization, and the idea of filter bubbles, there’s a sense of a general symmetric, technologically driven phenomenon, particularly on the media side. The asymmetry strongly suggests that we’re not looking at a technologically determined phenomenon, but rather at a politically, culturally, socially driven phenomenon, that uses the affordances of the technology to leap over the traditional gatekeepers and create its own media ecosystem.”

How right-wing media shaped broader media narratives

“A critical factor here is the ability to shape discourse in the traditional media…one very clear outcome that you see is that Clinton’s coverage was primarily on scandals, and very little on substance, [while] Trump got through his issues much more than scandals. Specifically, the focus was on Clinton’s emails, secondarily on the Clinton Foundation…whereas for Trump, it’s immigration, it’s jobs, and even trade, more than any of the scandal issues…Immigration is Breitbart’s topic, not Fox News. Breitbart forced immigration on the GOP, they didn’t want it.”

The challenges ahead, and the role of journalism

Nothing makes people care about an institution more than the clear sense that they’re about to lose it…

“If we think that fake news is the problem, we ask questions like, how can Facebook and Google change their advertising algorithms to deter people trying to make a buck? Or, how do we create a Facebook flag for users to forewarn of fake news? This may not be entirely irrelevant, but fundamentally, when we understand that we’re in a universe of disinformation and propaganda, we face the basic question of: How do we maintain a democracy in the presence of intentional efforts to deny the validity of basic methods of defining the range of reasonable disagreement? How do we maintain democracy when all the professions that claim to have pre-political basis for shared knowledge, on which citizens can come together to understand their shared fate, are challenged? It’s journalists, it’s scientists, it is judges, each of these mechanisms of independent judgement are challenged. How can we hold governments accountable when shared knowledge of certain facts are lost?”

“I will emphasize one optimistic fact from all of this. The traditional media continue to maintain a role, not perhaps among the elites of the radical right, but in the broad population. And there is an opportunity for a golden age of journalism now, because nothing makes people care about an institution more than the clear sense that they’re about to lose it, and the consequences of losing it. Particularly for journalists…understanding your professional role not just as telling a good story, not just as making money for your organization, but fundamentally, about being a major source of independent truth on which a democracy can be built, has never, or at least not for a long time, been so palpable in the United States.”

Article and photo by Nilagia McCoy of the Shorenstein Center.