Commentary

Rethinking Public Media, Together

Reports & Papers

Journalism, Media Business Models, Media Creation, Media Standards & Practices

The views expressed in Shorenstein Center Discussion Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University. Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important issues and challenges in media, politics and public policy. These papers are published under the Center’s Open Access Policy. Papers may be downloaded and shared for personal use.

Download a PDF version of this paper here.

America’s local newspapers are in steep decline, creating a deficit in local news. In affected communities, civic life is receding, social cohesion is declining, misinformation is increasing, and governmental accountability is weakening.

The question our study sought to answer is whether local public radio stations can substantially help meet the deficit in communities’ information needs resulting from the decline of the newspaper. To address the question, a lengthy online survey of National Public Radio’s member stations was conducted. The survey was sent to 242 stations. Replies were received from 215 stations, for a response rate of 89 percent.

The study’s main findings and recommendations are the following:

The weakening of local news is by now a familiar story. As digital change drove down local newspaper circulation and advertising revenue, cutbacks in news staff began, then deepened. Some dailies have shut down while others have shrunk their page count or delivery days. Digital subscriptions have risen but digital ads generate far less revenue than print ads.

Since 2000, more than 200 local dailies and thousands of local weeklies have closed with more on the way. Meanwhile, the number of employees at daily papers has dropped from roughly 75,000 to 30,000.1

Responses to the decline have ranged from encouraging digital startups to luring billionaires to become owners of local dailies. But the number of interested billionaires is limited, and most digital startups have struggled to generate substantial revenue and audience.2 Foundations have joined in, but their contributions compensate for only a small fraction of the loss. Local papers now take in less than $10 billion annually in advertising and circulation revenue compared to nearly $50 billion two decades ago.3

If the issue of declining newspapers was simply one of lost jobs, it would be an issue of concern on the level of the closing of a local factory. But the newspaper is more than just another local employer. For more than two centuries, local papers have provided residents a shared identity and purpose. Recent studies indicate that virtually every aspect of local civic life is at risk when the local paper shuts down.

In these communities:

As the Knight Foundation’s Eric Newton noted, local news gives people the information they “need to run their communities and their lives.”10 Without that information, there is a breakdown in residents’ ability to work through their problems, hold officials accountable, participate in civic and political life, and relate to one another and their community.11 Without access to the information that binds a community, it stops acting like a community.

Largely overlooked in the effort to save local news are the nation’s local public radio stations. The reasons are somewhat understandable. Radio is an older medium that itself has suffered audience decline. It also operates in a crowded space. Unlike a local daily, which largely has the print market to itself, local public radio stations face competition from other stations. Perhaps the belief that public radio is pitched to the interests of those of higher income and education has also kept it largely out of the conversation.12

Nevertheless, there are reasons why local public radio should be part of the conversation. The news media have a trust problem. They were one of the nation’s most trusted institutions in the 1970s but now are one of the least trusted.13 Trust in public broadcasting has declined but it ranks above that of other major U.S. news outlets.14 Moreover, public radio communicates through a medium where production costs are relatively low – not as low as that of a digital startup but far less than that of a hard-copy newspaper or television station. As well, the signals of local public radio stations reach 98 percent of American homes including those in “news deserts”—places that today no longer have a daily paper.15 In addition, the audience for local public radio has been more resilient to loss than that of other traditional news outlets16 and, unlike other local media, the number of local journalists in public media has increased in recent years.17 Finally, local public radio is no longer just “radio.” It has expanded into the digital space and has the potential to expand further.

A skeptic might concede these points but say that local public radio will never have the audience reach and coverage depth of local newspapers at their peak. That’s true, but market monopolies like those once enjoyed by the local newspaper and the three broadcast networks are a thing of the past. In today’s fragmented media environment, the information needs of local communities will be met, if they are to be met at all, by less comprehensive outlets.

The question, then, is whether local public radio can substantially help fill the gap in communities’ information needs created by the decline of the newspaper. The question requires two considerations:

Any such assessment must account for differences in communities’ information needs. The problem created by the decline of the newspaper is most acute in communities with the largest information deficit—places where local news is poor in terms of its quantity and quality. What is public radio’s potential in these locations, some of which are “news deserts”?

This study examines local public radio stations in the context of the communities in which they operate. It explores the information “health” of these locations and the local public radio station’s position in terms of its news coverage and audience reach. The study then assesses, from the perspective of local stations, the projected impact of substantial new funding on their coverage and reach, and what uses they would make of the funding. It then “tests” their assessments, asking whether local stations recognize the obstacles to expanding their footprint in their community, particularly in what can be called “hard places”—those where local stations face the largest obstacles. The report concludes with an assessment of what could be done to position local stations to substantially increase their contribution to the information needs of local communities.

The evidence for this study comes from a survey of the NPR “member stations” that NPR uses for its own periodic surveys.18 There are roughly 250 such stations, which operate more than 1,000 station signals nationwide.19 For our survey, we omitted the station in Guam and contacted only one station in cases where the same administrative and reporting staff manage more than one member station. That reduced the number of stations that we contacted to 242. Of these, 215 responded. The response rate was 89 percent, which is exceptional for a lengthy online survey. (The survey questionnaire is provided in Appendix B.)

Of our respondents, 57 percent actively managed the station, typically carrying the title of president, CEO, executive director, general manager, or station manager;20 38 percent were the news director or an equivalent title, such as content director;21 and 5 percent held a different position.22 Of the responding stations, 57 percent were university licensees, 28 percent were community licensees, 6 percent were government licensees, and 9 percent were otherwise licensed. Roughly half (53 percent) of the responding stations described their primary service area as “local, including the surrounding area,” whereas the other half (47 percent) described it as “regional.”

Some stations in our survey have semi-autonomous affiliated stations, which are not part of the survey. The programming of WBUR in Boston, for example, is also carried on WBUH (located in Brewster, Massachusetts) and WBUA (located in Tisbury, Massachusetts). In such cases, the respondent was asked to answer questions solely in the context of the major station, which in this case would be Boston’s WBUR.

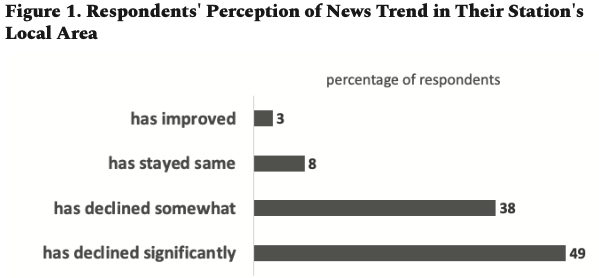

The decline in local news was apparent to our respondents (see Figure 1). When asked about the news trend in their communities, a mere 3 percent said that the quality and quantity of local news had improved and only 8 percent judged it to have stayed the same. The others perceived a decline in news quality and quantity with half describing the decline as “significant.”

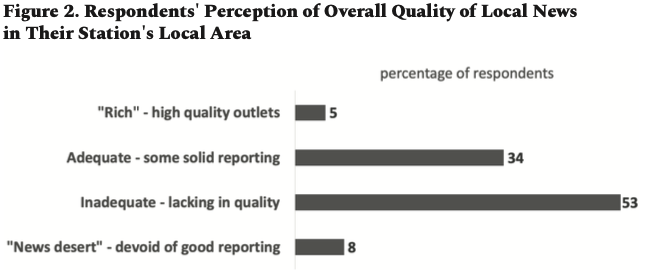

When asked, excluding their station, what they perceived to be the state of news and public affairs coverage in their community, only one in twenty (5 percent) said their locality had a “rich news environment,” described as one with “high-quality news outlets that invest heavily in local reporting” (see Figure 2). A third (34 percent) called their local news environment “adequate,” described as one with “news outlets that regularly conduct substantial local reporting.”

The other respondents had a more pessimistic assessment. Slightly more than half (53 percent) of respondents called their local news environment “inadequate,” meaning that it had “some quality local reporting” but that it was “generally lacking in quantity and consistency.” And 8 percent of respondents perceived their locality to be a “news desert”—one nearly devoid of good local reporting.

For the rest of this report, local news environments will be grouped into two categories. The term “strong news environment” will be used to describe localities that respondents judged as having either an “adequate” or “rich” news environment while “weak news environment” will describe those judged as “inadequate” or as “a news desert.”

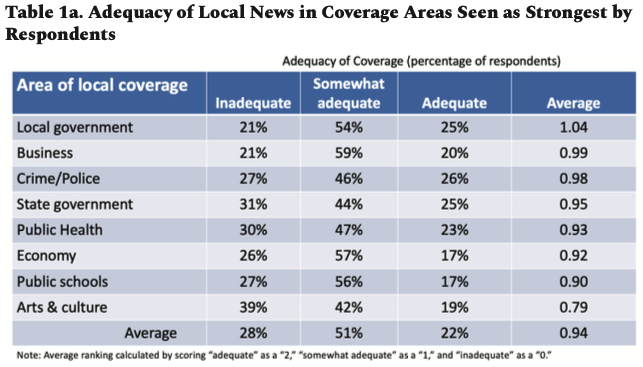

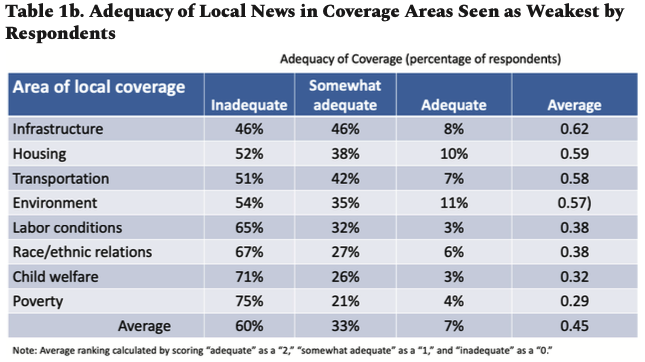

What do stations see as the major gaps in local reporting? To address this question, we asked respondents to evaluate the adequacy of their community’s local news for 16 coverage topics.

Table 1a shows the eight topics that respondents saw as having the strongest coverage. Except for public health, which presumably ranked high because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the topics are what can loosely be called the staples of local public affairs reporting—government, business, crime, the economy, and schools. As can be seen, even for these topics, respondents did not have a particularly high opinion of the coverage. Indeed, respondents were somewhat more likely on average—28 percent to 22 percent—to say that local coverage of these topics was “inadequate” rather than “adequate.”

Table 1b shows the eight coverage topics that respondents judged the weakest. They are what can loosely be called local social issues, including race, labor conditions, child welfare, and poverty. Large numbers of respondents in each case judged the local coverage to be “inadequate.” Poverty coverage was at the bottom, with 75 percent of respondents describing it as “inadequate” and a mere 4 percent saying it was “adequate”—a 71 percentage-point difference.

The quality of the coverage for every topic was judged to be significantly lower in communities with weak news environments. Local government coverage, for example, averaged 1.41 for respondents from stations in strong news environments and 0.81 for those in weak ones. Across all 16 coverage topics, the average was 1.06 for respondents from stations in strong news environments as compared with 0.49 in weak ones.

In general, the survey indicates that the decline in local news is most acute on topics where news outlets were not all that strong in the first place. Respondents’ assessments also support the view that local news has broadly declined in its quality and quantity. Even the topics deemed as having the best coverage were not rated highly.

Local public radio stations operate in a competitive environment. Unlike the local newspapers in the pre-broadcast era, local stations contend with other outlets for residents’ attention. Moreover, local public radio stations vary in their capacity. Some have substantial newsrooms while others have a thin reporting staff.

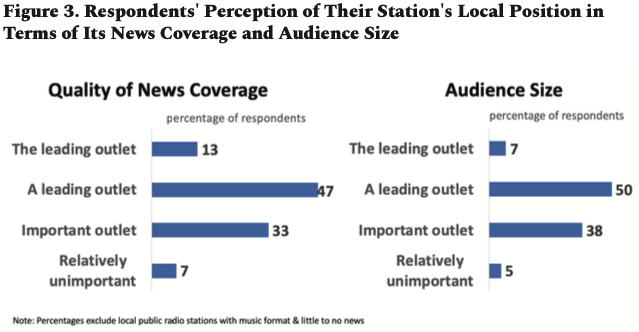

Where did respondents place their stations in the mix of local news outlets? To address this issue, we posed two questions. One asked the respondents to describe their station’s local position “in terms of the comprehensiveness of its local news and public affairs coverage.” The other asked them to place it in “terms of audience size.”

As can be seen in Figure 3, more than half of the respondents considered their station to be a leading local outlet in terms of news coverage with one in eight – 13 percent—claiming it to be “the leading outlet.” Nearly all respondents judged their station to be at least an important local outlet. Only 7 percent described it as “relatively unimportant.”

When it comes to audience reach, respondents were only slightly less likely to see their station as a vital part of the local news system. Although few respondents placed their station at the very top locally in terms of audience reach, only 6 percent said it was “relatively unimportant.”

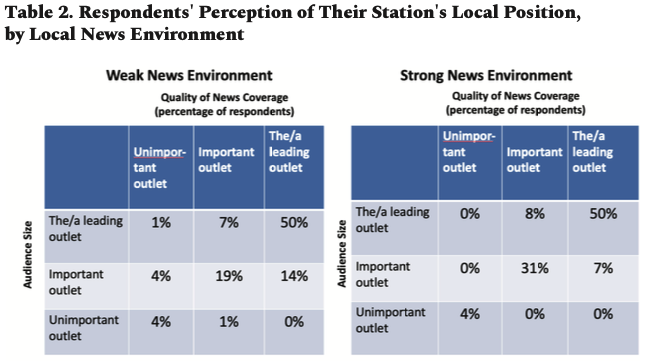

A station’s contribution to a community’s information needs rests on both the quality of its coverage and the scope of its audience. Only 3 percent of respondents identified their station as both “the leading outlet” locally in terms of news coverage and “the leading outlet” locally in terms of audience reach. When a lower standard is applied—whether respondents claimed their station was “a leading” or “the leading” outlet in both news coverage and audience size—half (51 percent) of the local stations met the standard.

It might be assumed that a station’s position in the community would depend on the overall strength of the area’s news outlets. That is, in communities with weak competitors, the local public radio station could be expected to be a more significant outlet than in communities with strong competitors. That expectation was not met (see Table 2). Respondents in weak news environments were marginally less likely to see their station as a leading outlet. An explanation for this finding will be discussed later in the context of what can be called “hard places”—the communities where local public radio stations have had the most difficulty establishing their station as a substantial source of local news.

How large is the footprint of public radio stations in their local areas? To assess that question, we asked respondents about their stations’ constituencies.

The listening audience remains the core constituency of local public radio stations. Respondents reported a median of 90,000 cumulative weekly listeners with roughly a tenth claiming 300,000 or more such listeners and a fourth claiming 30,000 or fewer.

Small donors have always been a relatively small proportion of those who consume local public radio, which is reflected in our findings. The median number of small donors per year, as reported by respondents, was 5,000. Less than 10 percent of the respondents reported that their station had 50,000 or more donors per year.

Local stations have been expanding their digital footprint, which is apparent in our survey. As reported by our respondents, the median number of unique monthly website visitors was 40,000 whereas the median number of social media followers was 14,000, although here again there was wide variation. A fifth of respondents claimed that their station had 200,000 or more unique monthly website visitors, whereas nearly a third said it had 20,000 or fewer. The difference was more pronounced for social media followers—nearly half of respondents claimed their station had 10,000 or fewer followers while only an eighth claimed 100,000 or more.

Podcast listeners are a relatively new public radio constituency, and three-fifths of respondents said their station did not produce podcasts. Of those that did, the median number of monthly listeners was 7,500 with more than half claiming 5,000 or fewer listeners and a seventh claiming 100,000 or more listeners.

Newsletters are also a relatively new offering of local stations, and a fourth of respondents said their station did not have a newsletter. Of those that did, the median was 5,000 recipients with a mere twentieth reporting 50,000 or more recipients. Finally, two-fifths of respondents said that their station stages local events, often featuring speakers on topics of interest to the local community. Among these stations, the median yearly attendance was 500 people with only a sixth of these stations saying they had hosted 5,000 or more people.

On key indicators, stations in strong news environments are better positioned than those in weak news environments. Stations in strong news environments, for example, averaged 151,085 cumulative weekly listeners and 20,101 yearly small donors compared with 117,548 listeners and 11,521 donors for those in weak news environments.

Public radio’s on-the-air audience has been slowly declining due to the popularity of audio alternatives like podcasts and news audiences’ increased preference for online content.23

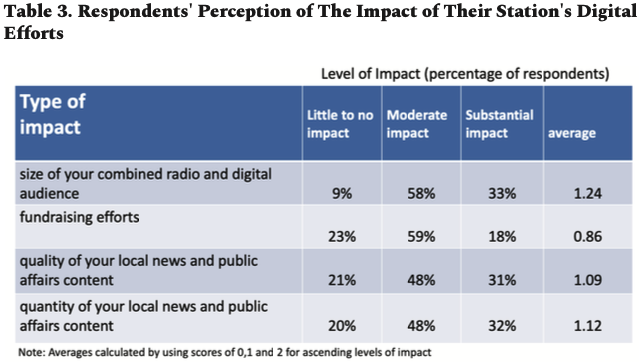

The distribution and consumption of news have changed fundamentally, and NPR has long urged its member stations to expand their digital efforts. How substantial has their response been? To address this question, we asked respondents to indicate the priority their station has assigned to “digital transformation.” Three out of five (59 percent) respondents said it had been a “high” or “very high” priority. Most respondents also claimed that it has had a “moderate” or “substantial” impact on the size of their total audience, their fundraising, and the quality and quantity of their news coverage (see Table 3). Of these, audience size was seen as the area in which digital transformation has had the largest impact. Fundraising was seen as the area that has benefited the least. Fundraising was, in fact, the only area in which more respondents said that there had been “little or no impact” than said there had been a “substantial impact.”

Respondents were also asked what percentage of their total audience was attributable to their station’s digital offerings. The average was roughly 25 percent but there was wide variation with a fourth of respondents attributing 10 percent or less of their station’s audience to digital while a fourth reported 30 percent or more.

Stations in strong news environments were more likely to have embraced digital transformation than those in weak news environments, but the differences were concentrated at the extremes. In the strong news areas, 7 percent of respondents said digital transformation had been a “low” or “very low” priority for their station while 32 percent said it was a “very high” priority. The corresponding numbers in the weak areas were 14 percent and 21 percent.

Most local public radio stations have small annual budgets relative to local newspapers or TV stations. They also can get by with less. Radio production is less expensive than newspaper publication or television production. Among the stations represented in our survey, the average overall budget as reported by respondents was $5,300,000, although some had annual budgets exceeding $20 million. We also asked respondents to estimate the amount of the annual budget dedicated to news and public affairs. The average was roughly $1,725,000, which is a significantly smaller amount than that of the average local daily newspaper.24

Stations with small budgets have an additional disadvantage when it comes to funding news and public affairs programming. There are costs associated with simply getting a station on the air and doing the fundraising necessary to keep it on the air. Such costs necessarily come first. Among the bottom half of stations in terms of budget size, only 22 percent of the total budget on average was dedicated to the production of news and public affairs. Among the top half, the figure was 35 percent.

For local public radio stations to play a more substantial role in filling the information deficit created by the decline of local newspapers, they would need significantly more funding.

When asked if they would accept such funding on the condition that it be used to expand local news and public affairs coverage, 86 percent expressed interest, with 7 of every 8 of them expressing strong interest. Ten percent said it was unlikely that their station would accept the funding while 4 percent said they were not sure. Nearly all of these have a music format. A format change would undermine their “brand.”

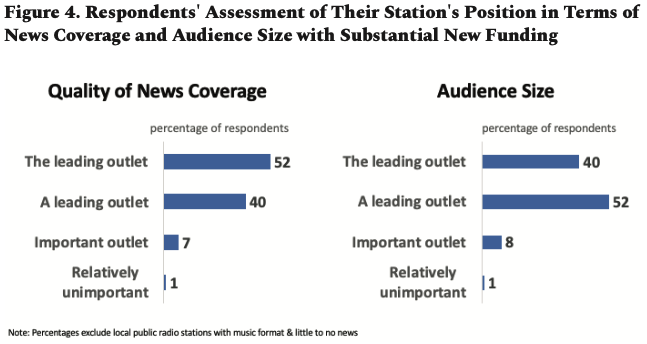

For stations with an interest in new funding, we asked respondents to project the funding’s impact. What effect did they think it would have on their station’s position in the local news environment in terms of the quality of coverage? In terms of audience size? Their responses can be seen in Figure 4.

In terms of the quality of their news coverage, fully half (51 percent) of the respondents said additional funding would make their station “the leading outlet” in their community (compared with the 13 percent who currently place their station in that position). An additional 41 percent said it would make their station “a leading outlet.”

When it comes to audience size, respondents were only slightly less optimistic. Forty percent said that additional funding would make their station “the leading outlet,” a nearly six-fold increase from the 7 percent who currently make that claim. An additional 52 percent claimed that the funding would make their station “a leading outlet.”

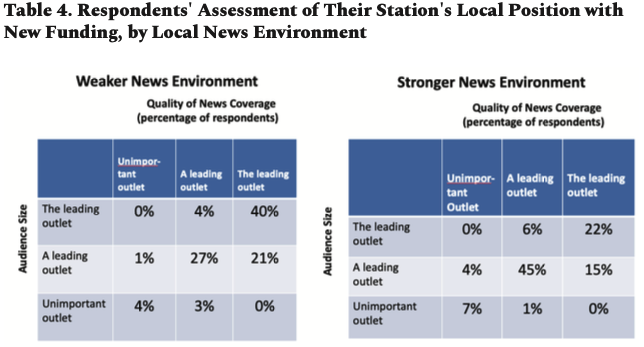

As indicated previously, a station’s contribution to a community’s information needs rests on both the quality of its coverage and the size of its audience. Earlier, when both aspects were looked at in the context of stations’ current position, only 3 percent of respondents identified their station as “the leading outlet” locally in terms of both news coverage and audience reach. When respondents projected the impact of new funding, the percentage jumped to 35 percent—a third of all stations. Moreover, a remarkable 84 percent of respondents claimed their station would become either “the top” or “a top” local outlet in terms of both quality coverage and audience size.

By this indicator, as can be seen in Table 4, the impact of new funding would be greatest for stations in weak news environments. Respondents in 40 percent of these communities claimed that the new funding would make their station “the leading outlet” in terms of both news quality and audience reach compared with 22 percent in strong news environments. Presumably, the difference reflects the level of local competition for the top spot. In many of the low-information communities, the local paper has closed or been hollowed out.

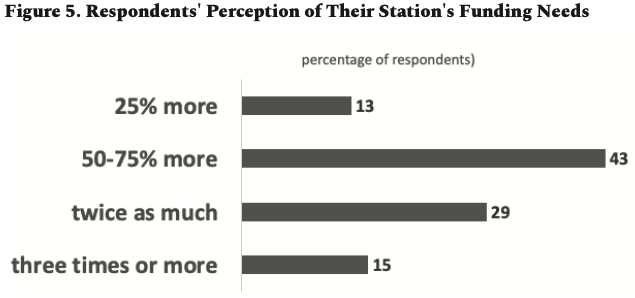

How much new funding do local public radio stations believe they would need to achieve a more prominent position in their communities?

To address this question, we asked respondents to specify the percentage increase their station would require. The responses varied widely, as can be seen in Figure 5. One in eight indicated a 25 percent increase would be needed while three in eight said that a 50-75 percent increase would be required. Roughly a third said a doubling of their station’s budget would be needed while roughly one in six cited a tripling of the budget or more.

As would be expected, respondents from small-budget stations were more likely to say that their station would need to double or triple its budget. Stations with smaller budgets are located disproportionately in weak news environments, which helps explain their proportionally greater budgetary need. Whereas 30 percent of respondents from stations in strong news environments said their station would need a doubling or more of its budget, 55 percent of those in weak news environments claimed it would need that level of additional support.

What is the dollar amount behind these estimates? To get a rough idea, we took each station’s current budget and multiplied it by the percentage increase that it said it would need. The median annual amount per station was roughly $1,300,000.25 Adding that amount to the current median annual news budget ($1,725,000) would raise the amount to roughly $3 million.

The overall price tag for expanding the coverage and reach of local public radio would be markedly lower if the funding was targeted at stations in the communities most in need. Stations with budgets exceeding $20 million are in media-rich places like Boston, New York, Washington, and Los Angeles, and many of the stations with budgets in the $10-20 million range are in cities where other news outlets provide reasonably solid local coverage. These larger stations would need the largest infusion of actual dollars to greatly strengthen their local position.

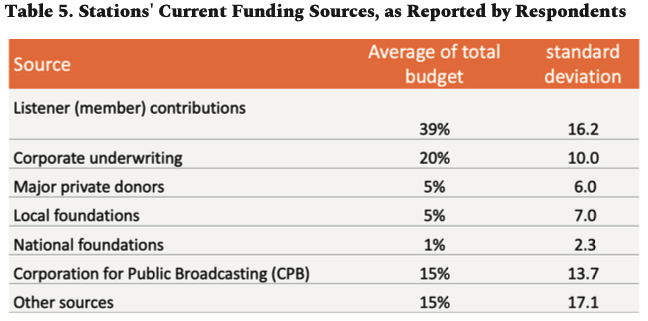

Public radio is largely funded by local sources. Local stations receive some funding from non-local sources but are responsible for raising most of their funds. Can they attract significant new funding through their own efforts?

Table 5 shows the breakdown of stations’ current funding sources, as reported by the respondents. Listener (member) contributions constituted the largest source of funding, accounting on average for 39 percent of a station’s total budget. Corporate underwriting was second, constituting 20 percent on average. Large private gifts and local and national foundations each accounted for 5 percent or less. Funding from CPB and “other sources” each accounted for 15 percent of the funding on average. The “other sources” included, for example, the funding that colleges and communities provide their licensed stations.

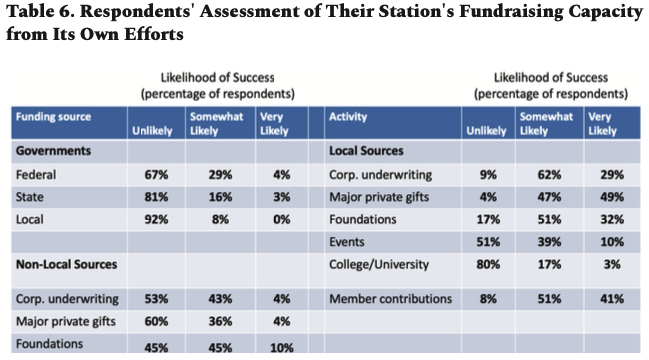

We then asked respondents to assess whether their existing funding sources could reasonably provide “substantial new funding.” Their responses are shown in Table 6.

Local stations don’t expect much help from any level of government. The federal government is seen as a more likely source of substantial new funding than state or local government but only in relative terms. A mere 4 percent of respondents believed that it was “very likely” their station could obtain substantial new federal funding compared with 3 percent from state government and 1 percent from local government.

Nor did respondents see non-local entities as promising sources of new funding. Even in the case of non-local foundations, which ranked above non-local corporate underwriting and non-local major private donors as a potential funding source, only 10 percent of respondents saw them as a “very likely” source.

Stations were more optimistic about obtaining significant new funding from local sources, except in the case of local government. Half of the respondents (49 percent) thought it “very likely” that local major private gifts could be a source of substantial new funding. Small donor contributions (41 percent), local foundations (32 percent), and local corporate underwriting (29 percent) also ranked relatively high.

However, if these potential sources of substantial news funding are available at the local level, why haven’t local stations already tapped into them? The proportion of public radio users contributing to their local station, for example, has been relatively steady over the years, suggesting that a substantially higher yield is unlikely.26

Realistically, if local public radio stations are to substantially fill the gap in communities’ information needs resulting from the decline of the newspaper, the necessary funding would have to come in large measure from sources outside their communities and be raised by an entity or entities other than themselves.

A large infusion of funding would strengthen local public radio stations. But would it place them in the position they claim? Do they have a realistic view of their potential?

Even a partial answer to the question is inexact, but stations’ staffing provides a starting point. In asking respondents about the size of their station’s news staff, they were asked to include broadcast and digital reporters, editors, hosts, producers, and others who create local news/public affairs content in its various forms, as well as those who directly provide technical or other support to these individuals. In addition to full-time employees, we asked them to include part-time employees and any students, interns, or freelancers who contribute regularly.

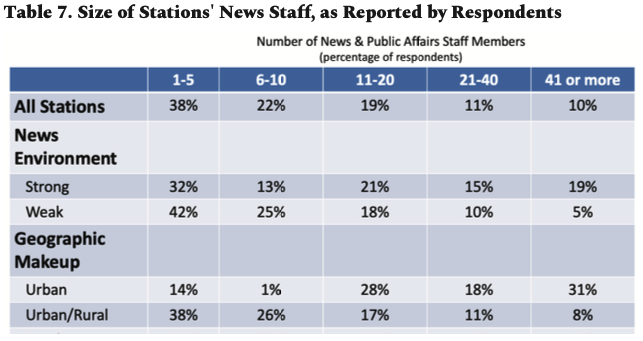

Despite the generous definition of what constitutes a staff member, most stations have a small staff (Table 7). Sixty percent of respondents reported that their station had a news staff of 10 or fewer people, and nearly two-thirds of these reported a news staff of 5 people or fewer. Only 10 percent of respondents reported that their station had a news staff larger than 40 people.

On average, the stations in strong news environments had larger news staffs. They were twice as likely as stations in weak news environments to have a news staff of more than 20 people. Staff size correlated even more strongly with stations’ geographical locations. Only 5 percent of stations that serve largely rural areas had a news staff larger than 20 people compared with 49 percent of those in urban areas. Three-fourths of the stations in rural areas had 10 or fewer news staff with half having 5 or fewer.

Another indicator of capacity is whether a station has a reporter dedicated to covering local government. A fourth of respondents said their station had such a reporter while a third said it was a part-time assignment or one shared with a reporter from another news outlet. Two in every five said their station did not have anyone assigned to cover local government. The pattern was similar for state government coverage except that, instead of a dedicated reporter, respondents were more likely to say they shared a statehouse reporter with another news outlet or outlets.

To obtain a fuller picture of stations’ capacity, we asked respondents a set of questions about their station’s news production. One question asked respondents about the number of hours of locally produced news/public affairs programming that was aired on weekdays between 6 am and 7 pm. If the content was repeated during the day, respondents were asked to include it as part of the total hours. The average (median) across all stations was 2 hours. A third (32%) of respondents reported their station aired an hour or less of local content, whereas only about a fourth (27 percent) reported more than 3 hours and a mere seventh (14 percent) reported more than 5 hours.

Some of this content was in the form of local news inserts in NPR programming to be aired on the hour or half-hour during weekday daylight hours. Over 90 percent of respondents said that their station aired inserts hourly (45 percent) or at least several times (47 percent) during the day. Only 8 percent reported not airing such inserts. However, in terms of covering portions of NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered, or other such national programs with lengthy local news inserts, only a third (31 percent) of respondents indicated that their station did so.

Much of the locally produced content is in the form of talk shows rather than news reports. Two in five respondents (43 percent) indicated that their station produced one or more daily talk shows focused on “local community issues.” A fourth (26 percent) said their station did not produce such shows each day but did so at least once a week. A third (31 percent) of respondents said their station did not produce talk shows.

On each of these indicators, as would be expected, stations with a larger news staff produced more local content than did stations with a smaller staff. It was also the case that stations in strong news environments produced on average more local content than those in weak news environments.

The evidence indicates that public radio in most locations is not all that local. In the 13-hour period from 6 am to 7 pm on weekdays, only about 2 hours of locally produced news programming were carried on the average station, some of it in the form of talk shows and some of it as repeat programming. The large share of public-affairs content on local stations is produced by NPR, PRX, PRI, and other providers and centers on national and international affairs. To be sure, local newspapers also offer a mix of local, national, and international content. But they devote proportionately more attention to local news—roughly twice that of local public radio stations.27

If local public radio stations received substantial new funding, how would they use it? The question bears on the issue of local stations’ potential. Do their priorities align with what would be required for them to become significantly larger players in their communities?

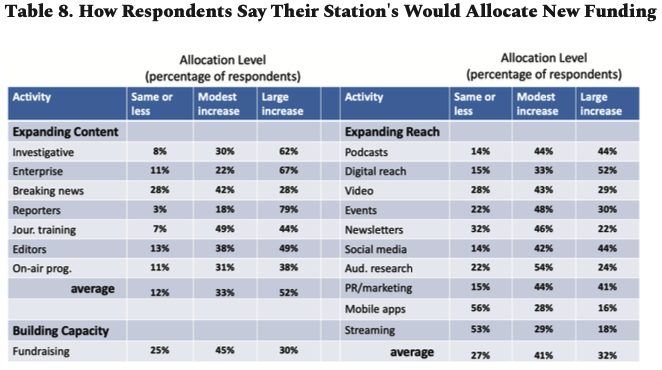

Local stations’ allocation preferences are shown in Table 8. What stands out is their emphasis on journalism capacity. The highest priority was hiring more reporters. Nearly 80 percent of respondents said reporting hires would receive a large spending increase. Expanding their capacity for enterprise journalism (67 percent) and investigative reporting (62 percent) was the next highest priority. Hiring more editors (49 percent) also ranked relatively high.

Expanding their station’s audience size was a lower spending priority for most respondents. Of the survey questions in this category, the top-ranked item was expanding the audience through new online/digital news offerings. Half of the respondents (52 percent) said this activity would be targeted for a large spending increase. Next on the priority list were podcasts (44 percent) and expanding the station’s social media presence (44 percent).

Stations’ tendency to favor journalism capacity over audience reach is evident in the average rankings. Whereas 52 percent of respondents on average said that their station would dedicate a “large increase” in spending to the typical journalism item, only 32 percent said the same of the typical audience-reach item.

A journalism-heavy strategy is an imperative for most local public radio stations. Their news staff is far too small for them to provide quality comprehensive local coverage on an ongoing basis, a problem made more acute by audiences’ interest in timely on-demand news. A journalism-heavy strategy is also necessary for local stations to retain and grow their audience. Without broad local coverage, public radio stations cannot expect to become the “go-to” source for local news in their communities.

Nevertheless, content alone will not give stations the local position they seek. Today’s media system is fragmented and hyper-competitive. Local stations compete with other outlets for people’s attention, which requires an outreach strategy. This imperative does not appear to loom large in the thinking at some stations.28 In response to a survey question that asked about obstacles “to your station’s ability to attract a significantly larger audience,” respondents overwhelmingly cited content-based limitations—insufficient on-the-air and digital resources. Only about one in five cited market competitors – “other news outlets” or “radio talk show outlets”—as “a significant obstacle.” That assessment underestimates the competitive threat to public radio posed by talk shows29 and other news outlets.30

The decline of local news is clearest in “news deserts”—those places where the daily paper has closed or been all but hollowed out. But they are not the only communities adversely affected by digital change. A larger number have seen major cuts in their newspaper’s local coverage.

These are “hard places” in terms of residents’ access to information about local affairs. Many of them are also “hard places” for local public radio stations to flourish.

Communities judged by our respondents to have a weak news environment were 10 percentage points more likely than those with a strong environment to be in a low-income area of the country. They were also 10 percentage points more likely to be in a predominately rural area.

Less affluent rural areas have been the locations hardest hit by the decline of local newspapers31 and pose a special challenge for public radio stations. The audience potential is smaller than in more urban areas, and the residents are less financially able to support local public radio. By every indicator of capacity, even when compared only with other stations in weak news environments, the stations in lower-income rural areas were disadvantaged. Their news staff, for example, was only half the size on average. Small donors provide another example. Whereas the stations in poorer rural areas had on average less than 3.000 contributing members yearly, the other stations in weak information environments had more than 8,000 such donors.

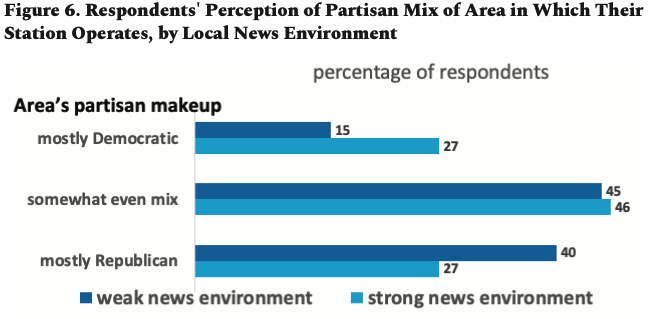

Stations in areas with weak news environments were also more likely to be in locations that are predominantly Republican (see Figure 6). Whereas stations in a strong news environment are as likely to operate in a mostly Democratic area as in a mostly Republican area, stations in a weak news environment are nearly three times more likely to operate in a Republican area than a Democratic one.

Republican areas pose a special challenge for public radio stations. In recent decades, many Republicans have left public radio in favor of conservative and Christian talk radio stations.32 On virtually every indicator of capacity, stations in a weak news environment that was mostly Republican were disadvantaged. In terms of contributing members, for example, the average for such stations was less than 4,500 members compared with more than 10,000 for other stations operating in a weak news environment.

A broader look at the challenge facing stations in “hard places” is gained by looking at stations’ funding models. Public radio depends heavily on member contributions. When examined as a percentage of the stations’ overall budgets, as reported by our respondents, the percentage was lower for stations in rural areas, stations in low-income areas, and stations in mostly Republican areas.33 The proportion was also significantly lower in areas with large minority-group populations.34 Such stations were more dependent on outside support. Funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), for example, was a substantially larger percentage on average of their station’s budget.

Of the “hard places,” the hardest are those that are working against all three obstacles to obtaining member contributions—rural, low-income, and mostly Republican. The proportion of their funding from member contributions was nearly 15 percentage points lower than stations that faced none of these barriers.

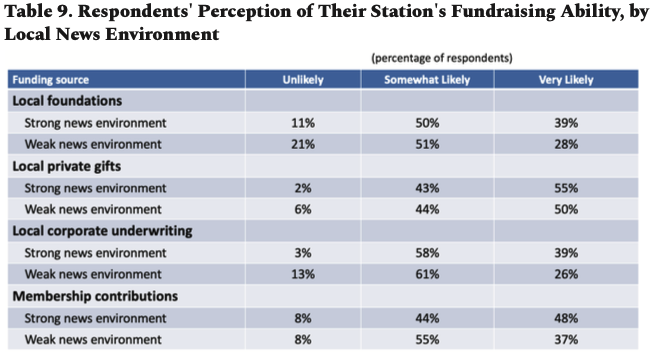

Looked at in broader terms—through the lens of all stations located in weak news environments—the notion of “hard places” is also justified. As can be seen in Table 9, respondents from stations in weak news environments were more pessimistic about the possibility that their station could generate substantially more funding through its own efforts. For each of the top-ranked sources of local funding—local foundations, local major private donors, local corporate sponsorships, and member contributions—respondents from stations in weak news environments rated the prospects lower than those in strong news environments. For example, roughly a third of respondents from stations in weak news environments saw small donors as a “very likely” source of substantial news funding compared with roughly half of those from stations in strong news environments.

The notion of “hard places” helps explain the earlier finding that local public radio stations operating in weak news environments were less likely to be prominent local outlets than those operating in strong news environments. Although they have less competition from other news outlets, that advantage is more than offset by the limits on their effort to become a more prominent outlet.

The harsh reality of local stations in “hard places” can be seen in their more limited participation in reporting partnerships that allow stations to gain the advantage of economies of scale.

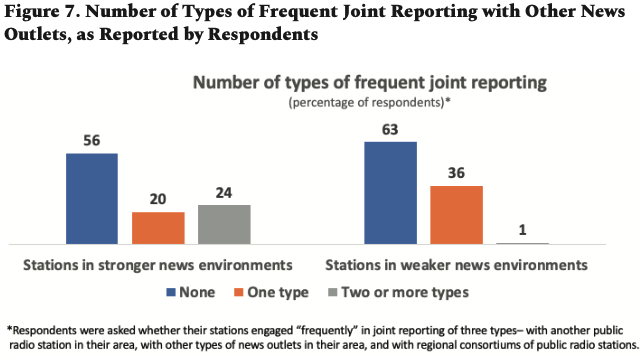

In our survey, we asked respondents about the frequency of their station’s joint reporting with other news outlets. A fourth (23 percent) reported frequent joint reporting with another public radio station in their general area while another fourth (26 percent) reported doing so through a regional consortium of public radio journalists. A smaller number (12 percent) reported frequent collaboration with other types of news outlets.

In each case, stations in weak news environments were less likely to engage in partnerships (see Figure 7). Whereas 24 percent of respondents in strong news environments said their station had frequently engaged in at least two of the three types of joint reporting we surveyed, a mere 1 percent of those in a weak news environment reported doing so.

What might explain the sharp contrast? Why do stations in information-poor environments seldom work in collaboration with other news outlets? Given their more limited resources, they should have a greater incentive to collaborate. In fact, however, their resource limitations are a barrier to joint reporting. For most of these stations, the news staff is so small that they can’t afford to share their journalists on a regular basis. Ninety percent of respondents in weak news environments said their station had ”too few reporters to be able to regularly assign them to partnerships.” They also indicated that their limited capacity made them an unattractive partner. A respondent from one of these stations said, “We see partnerships with strong newsrooms as the future for a small station like ours but have trouble forging collaborative partnerships despite our persistent efforts.”

Since the beginning of the Republic, the local newspaper has been the main source of community news. Even as television news in the 1960s came to play a larger role locally, newspapers with their larger news hole and staff remained the leading generators of local news. That era is ending and, in some communities, has ended—their local daily paper has closed.

The question that prompted this study is whether local public radio can help fill the information gap created by the decline of the newspaper. In some ways, local stations are well-positioned to be part of the solution. Local stations are locally owned and operated, positioning them to address their communities’ information needs.35 They also have a substantial following, one that has been more durable than that of other local news outlets. They are also committed to expanding their efforts.36 As one of our respondents said, “The need for the kind of journalism public media can provide grows more evident every day. The desire on the part of our newsrooms is strong.” Some stations are so concerned by their community’s information deficit that they have stretched their thin budgets to help offset it. “[For] most of our 49-year history, our station has been known for NPR news with local music and arts programming, but very little local news,” a small-market respondent said. “We have just committed to a news department startup. We’ve hired a news director and are now recruiting 3 reporters. This is a fiscal risk, but we owe it to our community.”

It’s also the case that local public radio stations blanket nearly the whole of the United States. They comprise a local network matched in scale only by local television stations, many of which feature sensationalistic coverage.37 Public radio is known for its quality programming, an advantage that is not easily overstated. Nor can the advantage of being a trusted local brand be overlooked.38 For citizens seeking local news, the local station is one of a limited number of choices. For other forms of content, including national news, there is far more competition. On NPR One, which is NPR’s streaming audio app that has both national and local content, local news is the content that is least likely to be skipped over.39

The federated structure of the public radio system is also a strength. Leading stations have been models of innovation for other stations, and decentralized control has allowed each station to develop in ways responsive to its community. The result has been a system that’s been remarkably resilient while becoming more robust, sophisticated, and innovative by the decade.40

The decline of local news has increased the importance of local public radio. Local newspapers are not the only place where local news is in retreat. The number of local commercial news stations has decreased,41 and local TV stations have been cutting news staff.42 In most places where the newspaper has closed, no print or digital outlet has emerged to take its place.43 Ironically, although there is more media competition overall than ever before, competition in the local news space has declined.44 The opportunity this presents has not been lost on public radio stations. “As our local newspapers have crumbled,” one respondent said, “we see a golden opportunity to increase our presence.” Said another, “Public media is positioned well to become the standard-bearer for local journalism if the resources exist to fund the work.”

Local public radio has its weaknesses. Many stations have been slow, for example, to respond to digital change. The over-the-air audience is graying. The public radio listening audience has declined in every age group except senior citizens.45 Five times as many Americans say they prefer to get their local news online as say they prefer to get it through radio.46 Although digital is a large part of the future of local public radio stations, it has been a difficult space for them to navigate.47 They are structured primarily to serve a listening audience—appointment users who seek a particular type of programming at a designated time from a specific outlet. Digital is the domain of on-demand users who seek a particular topic or the latest update. The websites of many local stations now get more traffic through search than through the home page. NPR’s digital search analyst Christine Macholan notes that increases in traffic are being driven primarily by “people searching for particular topics and getting to stations’ articles that are on their website.”48

A few public radio stations have developed impressive multi-platform newsrooms with a substantial range of broadcast and digital content,49 but even they have faced challenges in responding to digital transformation. Online users are substantially less likely than listeners to become regular users and donors.50 Search traffic is a benefit to commercial outlets because of their advertising model. It offers less payoff for public media. Realistically, local public radio stations do not have the option of withholding their content from digital platforms like Google and Facebook, but the platforms largely capture the monetary value of the content, determine how it will be positioned, and do not share user data in a way that would enable local stations to build a closer relationship with users.51

Digital platforms have also altered the nature of competition in the news space.52 The boundary that separated local and national news outlets in the broadcast era has been erased by digital. That earlier boundary worked to protect local outlets by limiting residents’ choices. Competition in today’s news space is asymmetric. National outlets like cnn.com and nytimes.com reach into communities throughout the nation. A local news outlet lacks the brand name and content to take online users away from well-known national outlets, but they can and have taken users away from local outlets. People have a finite amount of time to give to news, and national outlets have been capturing a disproportionate share of it.53 Ironically, NPR.org is one of those outlets. Its traffic has increased sharply in recent years, some of it at the expense of traffic to the sites of local stations.54

Another challenge facing local public radio, as with other news outlets, is that audiences have increasingly moved to outlets that cater to their values and interests. Public radio’s disproportionate appeal to Americans of above-average education and income is a function of an agenda that speaks to their concerns.55

Carrying NPR’s national agenda into local programming is fruitful in some locations but not others, particularly those that are rural and conservative.56 Public radio’s mandate to educate as well as inform can also distance stations from their community’s concerns. A staple of local commercial outlets—the weather—is a less-frequent topic on local public radio, even though surveys repeatedly show that it tops the list of things of greatest interest to local audiences.57 The point here is not that local stations should mimic commercial outlets. The public value of the content of public radio stations is their distinguishing feature.58 But local stations cannot meet a community’s information needs—or expand their audience—without taking the community’s interests and values more fully into account. Several survey respondents emphasized this point, saying it has helped them build their audience. Said one of these respondents: “We believe that our increased emphasis on local reporting as well as news, weather, and traffic updates has resulted in a substantial increase in audience, revenue, and recognition for our station. Our on-air membership totals have doubled during that time.” Another said, “We have to give up our preciousness . . . We have to meet information needs directly.” A third respondent said, “As local public radio seeks to fulfill its service mission, stations must connect with audiences that reflect the entirety of their communities.”

Nevertheless, the largest obstacle to a larger community role for local public radio is inadequate funding. Most stations do not have a news staff that is large enough to respond to the opportunity presented by the decline of the newspaper. Local stations’ comparative advantage in the competition for audience attention is the local news and public affairs programming they produce.59 It is what distinguishes them, not just from national news outlets, but also from non-news outlets, locally and nationally. But, as we’ve shown, most local public radio stations lack the news staff to be a major source of local news. Some stations are so understaffed that they generate little in the way of local news. A respondent from one of these stations lamented, “We have one full-time news person.”

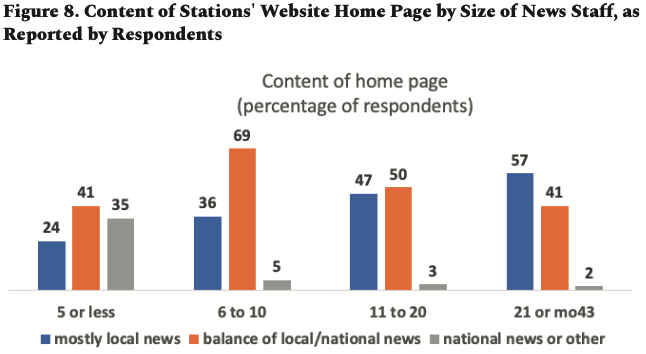

Even the slow response of stations to digital opportunities is largely attributable to understaffing. It takes staff time and technical expertise to transition to digital, and it takes staff time to generate digital offerings. Stations’ websites illustrate the staffing problem. Local stations have had less success than local newspapers in attracting users to their websites. The ratio of analog to online users is roughly 1:1 for the newspaper, whereas it is roughly 4:1 for radio stations.60 Moreover, whereas most of the newspapers’ online users access their paper’s content at least somewhat regularly,61 most of those who use a local public radio station’s site do so infrequently.62

One of the reasons can be seen in Figure 8. It shows, broken down by staff size, the composition of stations’ homepage. As can be seen, there is a direct relationship between a station’s staff size and the emphasis placed on local news. The larger the news staff, the higher the likelihood that local news will be featured on the homepage. A local station’s website cannot become the “go-to” place for residents seeking local news on demand if the station fails to provide it. As one respondent said, “We see lots of opportunity. . . . We just need more resources to accomplish that.” Said another, “It really all comes down to funding. “We are starved for resources.”

As we demonstrated earlier in this report, the great majority of local stations would embrace new funding and devote it to expanding their local coverage and audience reach. And there is no reason to think the opportunity would be wasted.

Local stations have demonstrated that they can do a lot with limited resources. As one respondent noted, “We are known to “punch above our weight.” That’s a strong argument for investing in local public radio. Substantial new funding would go a long way for another reason as well. As was noted earlier, there are up-front costs to getting a public radio station on the air and keeping it there. Those expenses come first, with funding for news operations coming out of what remains. It’s the reason that well-funded stations can devote a larger share of their total budget to news than less-well-funded stations. A very large share of any new money coming into local stations could go directly into news production given that the up-front costs are already built in.

In sum, with additional funding, public radio has the capacity to fill much of the gap in local news created by the decline of the newspaper. Strengthening local public radio stations is a democratic imperative.

Although the staffing problem is most pronounced at smaller stations, staff size at nearly every station falls far short of that of even a moderate-size daily newspaper. The Des Moines Register, for example, has a daily circulation of 35,000 copies and a 50-person newsroom—a staff larger than that of 95 percent of local public radio stations.

It is unrealistic to think that sufficient funding could be found to significantly bolster the news staff of every public radio station, much less sustain the increase. Choices would have to be made. Stations differ greatly in audience size, for example. Based on our survey, the top 25 stations in terms of the number of listeners have roughly 65 percent of the public radio audience. Given that they are in urban environments, they tend to operate in communities where the local newspaper retains a degree of vitality. Nevertheless, two-fifths of these stations are in communities that have a weak news environment. There are also many additional stations in such communities that have a listening audience in the 50,000 to 150,000 range. In part because they are more likely to be located in lower-income areas, stations in this audience range in weak news environments have news staff half the average size (10 staff versus 21 staff) of stations in the same audience range in strong news environments.

Funding should go disproportionately to the most promising stations in communities that have lost their daily newspaper or where it is being hollowed out. As indicated at the outset, these communities have lost more than their main source of local news. Their civic health is in decline on every dimension, from their residents’ understanding of their community’s needs to their ability to hold local leaders accountable to their level of civic engagement.63

Communities’ information deficit is not the only factor that should govern allocation decisions. Stations differ substantially in market placement, decision-making flexibility, priorities, competitive environment, in-house resources, ownership, leadership, and the like, and thus in the degree to which substantial new funding would position them to meet the information needs of their area. A study by Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism concluded, for example, that community licensees have generally been more innovative and responsive than university licensees or those that are part of a government agency.64 Nevertheless, any allocation formula that doesn’t take communities’ information deficit into account ignores the risk that attends the decline of local news. Democracy is imperiled when local news dies.

The threat to public life posed by the decline of community-based news and public affairs coverage is a powerful argument for securing new sources of funding for public radio stations in affected communities.

Stations in these communities should heighten their local fundraising efforts. Local corporate sponsors, local foundations, and local major donors have a vested interest in the civic health of their community65 and they should be made aware of the harm resulting from its news deficit. Although, as we indicated earlier, the affected communities tend to be in lower-income areas that offer limited local funding opportunities for public radio stations, the risks of inaction increase the likelihood that local leaders, perhaps even local government leaders, will respond. As one of our respondents said, “There is a great fear locally of the region becoming a news desert. Local community leaders are excited about our organization becoming the most important source for quality local journalism.”

The federal government could reasonably be asked to increase its support of local public radio. In other Western democracies, government funding of public broadcasting is upwards of $50 per capita. It is roughly $3 per capita in the United States. Opposition to increased federal funding of public media has come from conservative Republicans who see public radio as a liberal news outlet. Nevertheless, they might be persuaded to support an appropriation for stations in weak news environments, which are disproportionately rural and Republican. The 2022 bipartisan infrastructure bill, which provides funds for extending broadband into rural areas, could also be a basis for persuading Congress to appropriate additional funds. Because of limited resources, local stations in rural areas have been slower than stations elsewhere to embrace digital transformation. Congressional funding would help them to catch up and be better positioned to serve their newly connected communities.

State governments could also contribute more funding. State legislators typically have close ties to the communities they represent and could respond to funding appeals based on these communities’ civic health. Thirty-six states currently provide some funding for public broadcasting.66 Each of the three states that provide $4 or more per capita is a largely rural “red” state– Nebraska, South Dakota, and Utah.67

Given their stake in the quality of democracy in information-poor communities, national and regional foundations also need to be part of the solution. MacArthur, Knight, Ford, Sloan, Pew, Hewlitt, and the Carnegie Corporation are among the foundations that have generously supported public radio, although most of this support has gone to leading stations to make them models for other stations and enable them to produce programs for airing across the public radio system.68 The more pressing need now is funding for stations that serve communities where local news is in short supply. Foundations will have to take the lead for this to happen. As one of our respondents observed, “many rural and small stations do not have the connections” to successfully “petition major foundations.”

Funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) is a core component of local stations’ budgets but much of this funding gets returned to NPR and other producers in dues and fees for programs like “Morning Edition” and “Marketplace.”69 The dues and fees could be adjusted to reduce the financial strain on smaller stations in information-poor communities. Such stations already depend more heavily on CPB funding than do other stations, but they need additional help. As one respondent noted, “our core membership fees with NPR” reduce the money available for “our local reporting and public service efforts.” Some respondents felt that CPB and NPR policies generally favor large stations and that these organizations could do more, as one respondent put it, “to strengthen local outlets in smaller, rural areas where news outlets have disappeared, and with them a sense of community, connectedness, and empowerment.”

Even in the unlikely event that all these possibilities materialized, the new funding would not reach the required level. Most local stations, and particularly those in information-poor areas, are greatly understaffed. As we noted earlier, even with a generous definition of what constitutes news staff, 38 percent of stations have a newsroom of 5 people or less, and 60 percent have one of 10 people or less. Some stations are so short of staff that they do not do any original reporting, relying entirely on other local outlets for their news reports.70 Without very large increases in news staff budgets, even the more promising local stations cannot realistically hope to fill the information deficit resulting from the decline of newspapers.

Much of the large funding that is required would have to come from major private donors. Obtaining substantial new funding from major private donors should be within reach. The nation has seen the largest accumulation of private wealth since the Gilded Age, much of it from opportunities created by the communication revolution. Moreover, many digital innovators and entrepreneurs have made private philanthropy a priority. Public radio has not been high on their priority list but, as the adverse effects of the decline of the newspaper on communities’ civic health become clearer and more widely known, they could turn to it. As a respondent noted, “The best way to strengthen public media is to help convince more people and organizations that it is in their interest and the interest of society to fund public media.”

The leadership of a national fundraising campaign conceivably could come from an established entity like NPR, but a newly formed independent entity would likely be a better option. Such an organization, if properly constituted and broadly reflective of the interests of local stations, would lessen concerns about a conflict of interest and could more easily manage difficult allocation decisions. Our survey respondents recognized the value of having an independent entity make those decisions. “A strong national fundraising effort for public broadcasting would be good,” one respondent said, “but it needs to be handled by an entity other than NPR, APM, or [the] mega stations.”

This report has focused on the capacity of local public radio stations to help meet the information needs created by the decline of local newspapers. Their effectiveness in doing so will depend in part on whether their journalism staff is representative of the community it serves.

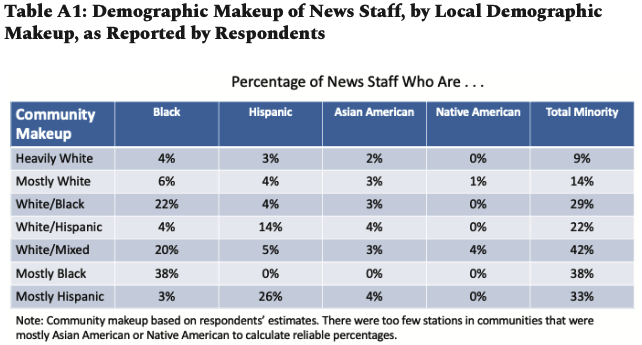

The issue of representativeness is partly a question of the degree to which a local station’s journalism staff reflects the racial and ethnic makeup of the community it serves. To address that question, we asked respondents to indicate the percentage of their journalists—including reporters, editors, hosts, producers, and any others who create local news and public affairs content—who were minority-group members.

As Table A1 indicates, there are relatively few minority-group members on the news staff at the typical station in a heavily white (4 percent) or mostly white (14 percent) community. But the average number increases substantially in communities that respondents judged to have a population consisting mostly of minority-group members or to be rather evenly divided between Whites and minority-group members. In largely Black communities, for example, nearly two of five journalists at local stations are themselves Black Americans. In largely Hispanic communities, about one in four journalists at local stations are Hispanic.

Nevertheless, the numbers indicate that the news staff at most stations is not a microcosm of the local community. Minority-group journalists are underrepresented even in communities where minority-group members constitute a majority.

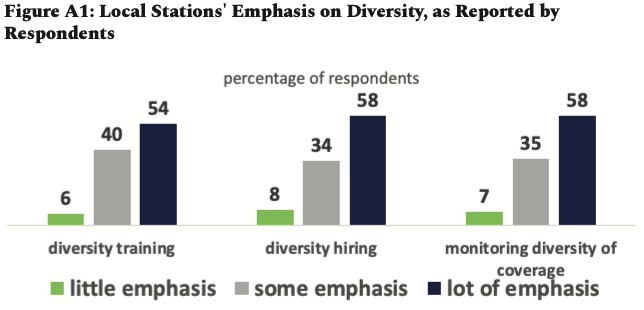

We asked our respondents about the efforts their stations were making to increase diversity. Their responses can be seen in Figure A1. On all three dimensions covered by our survey—diversity training, diversity hiring, and monitoring coverage for its diversity—most respondents indicated that their station had made it a priority.

In each case, as would be expected, diversity efforts were a higher priority at stations in communities where minority-group members made up half or more of the community’s population. For example, 71 percent of respondents from such stations said their station was placing “a lot of emphasis” on diversity training compared to 46 percent of respondents from stations in communities with a largely white population.

Thank you for participating in our local public radio survey. If you support more than one station, please respond in the context of your major news and public affairs station even if it also features music.

Your responses are confidential in the sense that we will not identify individual stations or respondents in our report. The report will instead examine tendencies, such as the percentage of stations that produce local talk shows.

These first 3 questions are for administrative purposes only. Again, we will not single out individual respondents or stations in the survey report.

Q1. Your name

Q2. Your email address

Q3. Your position

Q4. How many hours a day is your station on the air?

Q5. What are your station’s call letters?

Q6. What is the station’s zip code?

Q7. What is your licensee’s (station’s) ownership?

Q8. How much of your daytime programming is devoted to local news reports and local public affairs programs?

Q9. If a very large amount of new funding was made available to your station on condition that it substantially expand its local news and public affairs coverage, how likely is that your station would accept the funding?

NOTE: Respondents who were from stations that answered “4” to Q8 and “1” to Q9 were not questioned further. Virtually all these respondents were from stations that have a music format.

Q10. Thinking in terms of all local news outlets in your area except your own, what do you see as the trend in recent years in the quality and quantity of the area’s local news and public affairs coverage?

Q11. Thinking in terms of all local news outlets in your area except your own, which statement best describes the local news environment?

Q12. Thinking in terms of all news outlets in your area except your own, how adequate is local news in the following coverage areas? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “inadequate,” “somewhat adequate,” and “adequate”)

Q13. What is your station’s position in the local area in terms of the comprehensiveness of its local news and public affairs coverage? (Include audience for all your productions and not just your listening audience)

Q14. What is your station’s position in the local area terms of news audience size? (Include audience for all your productions and not just your listening audience.)

Q15. What is the approximate amount of your station’s overall annual budget? (A rough estimate is okay. If unable to make an estimate indicate as such.)

Q16. What is the approximate amount of your station’s annual budget local news and local programs? (A rough estimate is okay. If unable to make an estimate indicate as such.)

Q17. As a rough estimate, how much additional annual funding would you need if your goal was to substantially increase your audience reach and your local news and public affairs coverage. (Include audience for all your productions and not just your listening audience.)

Q18. If your station had the additional annual funding you indicated, what do you think would be its position in your local area in terms of the comprehensiveness of its local news coverage? (Include audience for all your productions and not just your listening audience.)

Q19. If your station had the additional annual funding you indicated, what do you think would be your station’s position in your local area in terms of news audience size? (Include audience for all your productions and not just your listening audience.)

Q20. If your station had the additional annual funding you indicated, how would you distribute the funds across the following categories? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “roughly same or less than current amount,” “modest increase,” “large increase,” and “we don’t have or plan to have this activity.”)

Q21. How would you describe the content of the home page of your station’s website?

Q22. Local public radio stations have been urged to undertake digital transformation (responding, for example, to the audience potential of streaming and mobile platforms). How much of a priority has digital transformation been for your station?

Q23. What do you see as the impact to this point of your station’s digital transformation in terms of…. (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “little to no impact” “moderate impact,” and “substantial impact”)

Q24. Roughly speaking, what percentage of your station’s audience is attributable to its digital offerings (as opposed to its radio broadcasts)? (A rough estimate is okay.) FOR THIS QUESTION, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “Enter percentage,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q25. Which statement best describes your station’s primary service area?

Q26. In general, what is the composition of your primary service area in terms of

Q27. Thinking now about the racial/ethnic diversity of your primary service area, what is the best description?

Q28. Thinking now only of the minority groups in your primary service area, what is the best description?

Q29. How many people work at your station? (A rough estimate is okay. Include full- and part-time employees and any students, interns, or freelancers who regularly contribute.) (FOR THIS QUESTION, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTION: “Enter number of people,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q30. How many people who work at your station are involved in creating local news/public affairs content? (A rough estimate is okay. Include full- and part-time employees and any students, interns, or freelancers who regularly contribute. Please include broadcast and digital reporters, editors, hosts, producers, and others who create local news/public affairs content in its various forms. Also include people who provide technical or other support to those directly involved in local news/public affairs content creation.) (FOR THIS QUESTION, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTION: “Enter number of people,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q31. On an average weekday, roughly how many hours of your over-the-air news/ public affairs programming is locally produced, as opposed to being produced by NPR, PRI, APM, BBC or other such source? (Include repeated local content in total number of daily hours. A rough estimate is okay.) (FOR THIS QUESTION, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTION: “Enter number of hours,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q32. Does your station produce local news inserts to be aired on the hour or half hour during the 6am-7pm period?

Q33. Does your station cover portions of Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and/or other such national programs with local news inserts?

Q34. Aside from local news inserts, does your station produce daily talk programs focused on local community issues?

Q35. Does your station produce programs that are picked up regionally or nationally by other stations?

Q36. Do you have a reporter(s) dedicated exclusively to covering local government?

Q37. Do you have a reporter(s) dedicated exclusively to covering state government?

Q38. How great an obstacle is each of the following to your station’s ability to attract a significantly larger audience? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “not a significant obstacle,” “somewhat of an obstacle,” and “significant obstacle.”)

Q39. How often do your journalists participate in . . . (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “not at all/rarely,” “occasionally,” and “frequently.”)

Q40. How important are the following obstacles to expanding partnerships with journalists outside of your organization? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “not an obstacle,” “minor obstacle,” and “major obstacle.”)

Q41. What’s the approximate percentage of your journalists who are . . . (Please include reporters, editors, hosts, producers, and others who create content; exclude technical and other people who support them. A rough estimate is okay. (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “Enter percentage,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q42. How much emphasis does your station place on the following? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “not much emphasis,” “some emphasis,” and “a lot of emphasis.”)

Q43. What’s your rough estimate of your station’s . . . (A rough estimate is okay) (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “unable to make reasonable rough estimate” or “enter number.”)

Q44. Where do you see opportunity for audience growth? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “no or minimal opportunity”, “moderate opportunity” and “substantial opportunity.”)

Q45. Approximately what percentage of your station budget is provided by . . . (A rough estimate is okay.) (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “Enter percentage,” or “unable to make reasonable rough estimate.”)

Q46. What’s your sense of the likelihood that your station through its efforts could get substantial new funding from? (FOR EACH ITEM, RESPONDENTS HAD THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS: “unlikely,” “somewhat likely,” and “very likely”)

Q47. We have three open-ended questions to conclude the survey. First, if your station has a system for tracking the impact of your journalism, please describe: (If none, enter NA.)

Q48. Second, if you have an example of where your journalism has made a significant contribution to strengthening civic life in your community, please describe (If none, enter NA)

Q49. Finally, we would be interested in any comments/suggestions you have for strengthening local public radio. We’d also be interested in hearing about innovative fundraising efforts that your station initiated that other stations could try. (If none, enter NA)

I would like to thank Charlie Kravetz and Phil Balboni for their wise counsel in developing the public radio station survey; Paul Haaga, Phil Kent, and Jarl Mohn for generously funding the project; Kevin Wren for his invaluable help in creating the sample, fielding the survey, and compiling the data set; Lindsay Underwood and Liz Schwartz for overseeing the report’s publication; and Nancy Gibbs and Laura Manley for their unstinting support and encouragement.

Thomas E. Patterson is Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. He is the founder of Journalist’s Resource, a website of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy dedicated to providing journalists with timely information on research findings relating to the topics on which they are reporting.

He is the author of numerous books and articles, including Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism and How America Lost Its Mind: The Assault on Reason That’s Crippling Our Democracy. An earlier book, Out of Order, received the American Political Science Association’s Graber Award as the best book of the decade in political communication. His first book, The Unseeing Eye, was named by the American Association for Public Opinion Research as one of the 50 most influential books on public opinion in the past half century.

His research has been funded by the Ford, Markle, Smith-Richardson, Pew, Knight, Carnegie, and National Science foundations. After serving in Vietnam in the U.S. Army Special Forces, Patterson earned his PhD at the University of Minnesota and then taught for two decades at Syracuse University before coming to the Kennedy School.

Commentary

Videos

Videos