Product Management and Society Playbook

Reports & Papers

A new paper by Marilyn W. Thompson, Joan Shorenstein Fellow (spring 2016) and former deputy editor of POLITICO, chronicles the rise and fall of the Presidential Election Campaign Fund, and explores whether the fund could still provide a viable way to address citizen frustration with the campaign finance system.

The Presidential Election Campaign Fund was conceived 40 years ago to level the playing field for political unknowns and to engage average citizens by allowing them to voluntarily check off a fund donation on their income taxes. At its height, the program boosted the candidacies of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, helped limit campaign costs and allowed candidates to forego frenetic cross-country fundraising. But as spending has exploded and fewer candidates have embraced the program in recent elections it has become irrelevant, writes Thompson, and is even dubbed “the losers’ fund.” With its strict spending limits and dwindling public participation, is the program worth saving? Thompson makes the case that increased public financing of elections would be a step in the right direction to rein in unchecked spending, and proposes policy solutions to modernize the fund for today’s campaigns. To contact Thompson about this paper, email marilynt2004@gmail.com.

Read a condensed version in The Atlantic.

Listen to Thompson discuss her paper on our Media & Politics Podcast:

Matthew King of suburban Tacoma, Washington, is a Democrat who believes the average American should donate to presidential candidates to thwart big money’s influence. Though he is looking for work, he feels so strongly about the issues that he makes small monthly contributions to Democratic candidates and causes.

“It’s democracy in action,” King said, describing his hopes for a president who will combine leftist ideals with strong Christian values. “Right now, money is our voice in politics.”[1]

Last fall, King, then working at a local Taco Bell, charged $20 to his credit card to support a candidate with potential, former Maryland governor Martin J. O’Malley. King did not know at the time that his donation would help O’Malley to navigate the cumbersome bureaucratic process through which his campaign would qualify for over $1 million under a relic known as the Presidential Election Campaign Fund.[2]

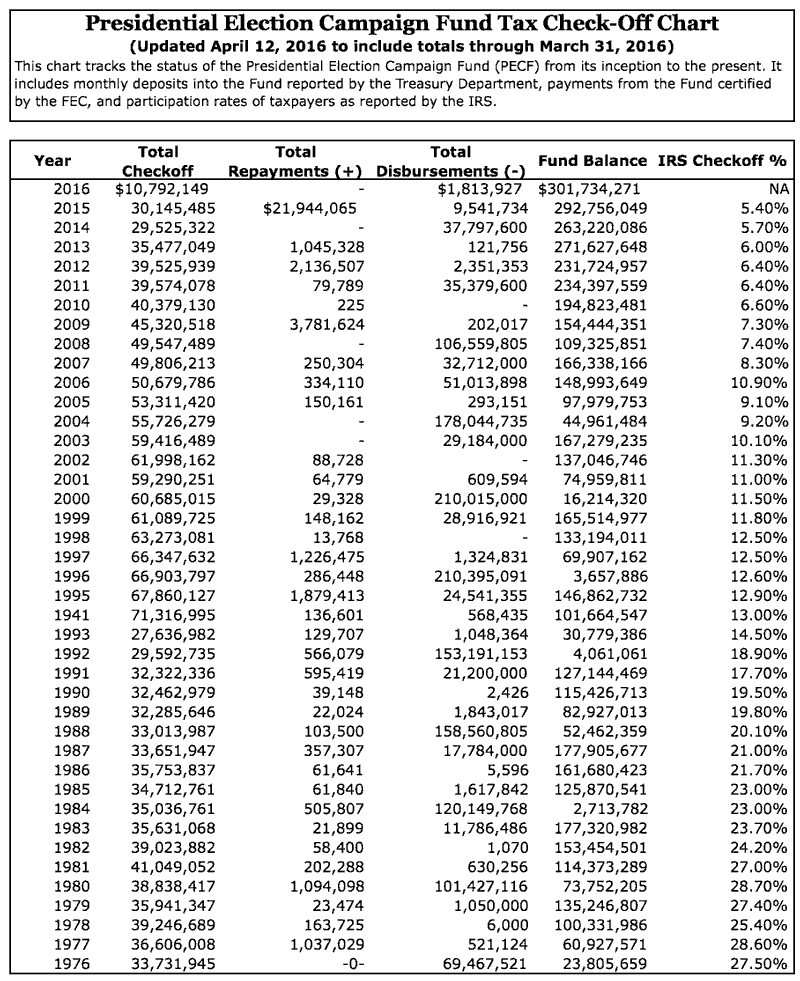

O’Malley was the only one of 23 primary contenders from the two major parties to seek public funds to help his 2016 primary campaign. More than $300 million still sits in the fund, and no other major party candidate wants to touch it.[3]

In a presidential campaign awash in money, with anticipated spending of up to $10 billion, the fund is a throwback to an idealistic time, before Supreme Court decisions unleashed secretive outside spending and wealthy individuals dominated campaign fundraising. It was conceived 40 years ago to level the presidential playing field, to give political unknowns a fighting chance and to engage average citizens by allowing them to voluntarily check off a fund donation on their income taxes. At its height, it allowed candidates to forego frenetic cross-country fundraising.

O’Malley was the only one of 23 primary contenders from the two major parties to seek public funds to help his 2016 primary campaign. More than $300 million still sits in the fund, and no other major party candidate wants to touch it.

The program boosted outsiders like Democrat Jimmy Carter and Republican Ronald Reagan, and for years it helped limit campaign costs. But as spending has exploded and fewer candidates have embraced the program, it has become irrelevant.

In recent years, an ever smaller percentage of taxpayers have checked off the box on their 1040 forms authorizing that $3 go into the fund. But says Anthony Corrado, a Colby College professor specializing in presidential campaigns, the fund now stands as “the last life raft of what was once the flagship of reform.”[4]

Everyone agrees the system is badly broken. Today the question is whether it should be wheeled into the shop for a total remodeling or hauled off to the scrap yard.

The fund was declared dead after 2008, when Democrat Barack Obama, after committing to it, abandoned it to raise enough money to swamp Republican John McCain, who did take the money. Obama proved that internet fundraising could empower small donors more directly than a tax check-off, a theory that also has guided the 2016 strategy of Democrat Bernie Sanders and allowed him to compete without relying on public dollars, corporate backing or SuperPACs.

But public financing advocates believe the check-off system deserves saving and have battled to preserve it while pushing for retooling. As citizen anger mounts over campaign finance abuses, the public financing concept has caught fire as a solution in more than three dozen state and local governments.

Yet Americans remain uncertain that public financing is the solution for fixing presidential elections, and declining check-off participation underscores that. In the post-Watergate years, as many as 28 percent of taxpayers checked the box. In 2015, the rate was a mere 5.4 percent.[5]

Public opinion polls show lukewarm support. Only 17 percent of participants in a July, 2015 Monmouth University poll agreed that public funding was “the best way to finance presidential election campaigns.”[6]

“Americans continue to be concerned about the effect of money in politics. But the polls also indicate that most of the public is not convinced public funding is the answer,” explained Kathleen J. Weldon of the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at Cornell University.[7]

Matthew King, our Tacoma citizen, was exactly the kind of voter the public financing system set out to engage – smart, committed and generous, even in trying times. But King, who is in his late 30s, said he did not check the box on his 2015 taxes and knows little about the public financing program. He gave directly to O’Malley. King also donates regularly to Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton and the Democratic National Committee.

Everyone agrees the system is badly broken. Today the question is whether it should be wheeled into the shop for a total remodeling or hauled off to the scrap yard.

Because O’Malley decided to pursue public funding, the support of voters like King helped him establish to the Federal Election Commission that he had backing in 20 states.[8] Under the system, a 2016 primary election candidate meeting this threshold could qualify for matching funds up to $48 million. If they made it to the general election and raised no private money, they qualified for an additional lump sum payment of $96 million.[9]

For O’Malley, the decision to work within the system was easy. As campaign manager David Hamrick recalled, “We needed the revenue, but it also philosophically meshed with our beliefs…We felt from a message standpoint and a philosophy standpoint that we were comfortable taking matching funds because we believe in them.”[10]

O’Malley’s FEC filing, however, signaled trouble to the press. As The Wall Street Journal put it, public money “will boost his coffers in the short term but makes him subject to strict spending limits that will constrain his ability to compete with better-funded rivals down the road.”[11]

It took a while for the FEC to process O’Malley’s filing. Since 2010, when demand dropped, a single employee spends about 10 hours a month – substantially more when paperwork peaks during the primaries – managing the fund.[12]

While he waited, O’Malley’s campaign borrowed $500,000 to get it through the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary.[13]

O’Malley’s filing finally reached the full FEC, a bipartisan body that rarely agrees on anything, and some grumbling ensued, according to Ann M. Ravel, the former commission chairwoman and its most outspoken member. The complaint centered on why taxpayers should fund a candidate on the verge of leaving the race. The filing then was kicked back to correct a math error. In the end, the commission is legally obligated to approve the funds and did so on January 20. O’Malley has received $1,088,929.[14]

The infusion of taxpayer money came too late to rescue O’Malley.[15] After a bleak showing in Iowa, O’Malley suspended his campaign.[16]

Over the years, candidates from both political parties have relied on public financing. The fund pumped more than $20 million each into the campaigns of Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Robert Dole and Pat Buchanan.

Jimmy Carter ranks as one of the program’s greatest success stories. Carter had only $42,000 at the end of 1975 and was in debt by May 1976 when public money saved his candidacy.[17]

Public funding kept Reagan viable until the Republican Party convention in 1976 and paved the way for his 1980 election.

That same year, California’s Republican Governor Ronald Reagan was “the most dramatic example of an underdog whose campaign needed public money,” according to an analysis by Michael Malbin, director of the Washington-based Campaign Finance Institute. In January 1976, Reagan had $43,497 to challenge incumbent President Gerald Ford, who had 15 times as much money. “If the challenger’s campaign had not received $1 million in public money in January, and another $1.2 million in February, he could not have continued,” Malbin wrote. Public funding kept Reagan viable until the Republican Party convention in 1976 and paved the way for his 1980 election.[18]

Public financing helped Democrat Gary Hart, who had about $2,500 in January 1984, compete against Walter Mondale, who had 800 times more money. Republican Pat Buchanan had only $12,000 on January 31, 1992, compared to incumbent President George H.W. Bush’s $8.9 million.[19]

Concludes Fred Wertheimer, a longtime campaign finance reform champion who now heads Democracy 21, “The bottom line is this system did exactly what it was supposed to do for more than two decades. The system was not perfect, but it allowed candidates to run competitive races for office. It kept the candidates away from private-influence money. It worked.”[20]

Yet debate over presidential public financing has always been wrapped in partisan politics and galvanized by scandal. Momentum is driven by whichever party is in power at the time.

Republican Theodore Roosevelt kicked off what can be considered the modern debate. His 1904 campaign had come under attack because of corporate funding, and Democrats in Congress had spearheaded passage of the Tillman Act to outlaw corporate contributions.

Roosevelt saw that he needed to be perceived “as a man who stood above politics.”[21] He had never been known as a campaign finance reformer, but he used his 1907 State of the Union message to Congress to float a “very radical measure.”

“The need for collecting large campaign funds would vanish if Congress provided an appropriation for the proper and legitimate expenses of each of the great national parties, an appropriation ample enough to meet the necessity for thorough organization and machinery, which requires a large expenditure of money,” he wrote.[22]

Roosevelt’s novel thinking did little more than plant a seed.

In 1960, Democrat John F. Kennedy spent $9.7 million and Republican Richard Nixon spent $10.1 million, breaking records in the first race driven by television advertising.[23] Kennedy responded to criticism over high spending by naming a commission to study the issue. Citing Roosevelt’s public financing idea, Kennedy suggested examining systems then in place in Puerto Rico and overseas.

As Kennedy explained, “I have long thought that we must either provide a Federal share in campaign costs, or reduce the cost of campaign services, or both.”[24]

Kennedy’s commission recommended a matching fund system in which individual contributions of up to $10 to major parties would be matched by public money, but the proposal languished in Congress.

Campaign finance scandals during Lyndon Johnson’s administration resurrected the issue. In 1966, Johnson recommended incentives that would “make it possible for those without personal wealth to enter public life without being obligated to a few large contributors.”[25]

He left the legislative work to the longtime chair of the Senate Finance Committee, Russell Long, the son of Louisiana Governor Huey Long. Russell Long in 1966 introduced the Presidential Election Campaign Act, which included a voluntary $1 check-off on individual tax forms. The fund would allocate $30 million to each political party to finance the presidential general election. Over strong objection, Long’s legislation passed as a rider to the Foreign Investors Tax Act, and Johnson signed it into law.[26]

Almost immediately, some of Long’s Democratic colleagues tried to overturn it. Sen. Al Gore Sr. (D-Tenn.) and Sen. Robert Kennedy (D-NY) led a repeal effort in 1968, arguing that the Long act “only supplemented private funds with public funds and would not effectively address the corrupting influence of private contributions.”[27]

Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.), the Senate Majority Leader, worked out a compromise. He recommended that the law be deactivated as the 1968 campaign season intensified, offering time for further study.

Growing fundraising disparities made the idea more palatable in 1971 when Sen. John Pastore (D-R.I.) sponsored legislation to revive the fund. The check-off was resurrected and set to start January 1, 1973.

The fund was incorporated into a more sweeping campaign finance measure in 1974 – the Watergate-inspired Federal Elections Campaign Act. It called for public money to go directly to candidates, not to parties, and extended the program to both primaries and general elections.

Yet the check-off system had structural flaws. The law dictated spending limits, including limits in each state, adjusted over time only for inflation. The rules failed to recognize that campaign dynamics would change, with early states wielding outsized influence.

Passing a law was one thing; getting taxpayers to designate $1 on their taxes was another.

The first year, taxpayers couldn’t figure out how to participate. The IRS required a separate form to authorize the check-off.[28] Only 3 percent of taxpayers participated in 1973.[29]

Senator Long met with Nixon’s IRS commissioner Donald Alexander to work out a solution. He argued that the check-off box needed to be featured on the first page of the 1040 form. The fix worked, and by 1974, the IRS reported that “10.7 million or 13.6 percent” had checked the box.[30]

For a time, so many candidates tapped into the fund that regulators feared bankruptcy. Congress bumped up the check-off amount from $1 to $3, and by 1994, the balance jumped from $30.7 million to $101.6 million.[31]

Yet the check-off system had structural flaws. The law dictated spending limits, including limits in each state, adjusted over time only for inflation. The rules failed to recognize that campaign dynamics would change, with early states wielding outsized influence.

In 2000, Republican George Bush opted to raise private funds and rejected public financing for the primary. Bush did take public money for the general election, as did his Democratic opponent Al Gore.[32]

At the time, concerns about campaign spending focused on “soft money,” large sums donated to parties that were then funneled to candidates, circumventing donation limits. Again, Congress stepped in to address abuses in 2002.

The public financing system sputtered along without mid-course corrections.

In 2008, the issue came to a head as Democrat Barack Obama faced off against Republican John McCain. As senators, both were campaign finance reformers, and Obama had pledged in November 2007 to accept presidential public funding.

But Obama abruptly changed course in June 2008. His campaign had tapped into the internet as a fundraising tool and was on track to raise $745 million in private contributions. Obama said he would forego $84 million in general election public funding, and he became the first president since Nixon to run for office without using public money in the general election. Obama outspent McCain, who took public money, four to one. [33]

Obama’s decision did not bode well for the future of presidential public financing, yet money continued to trickle in. House Republicans in 2011 unexpectedly targeted the system, arguing that taxpayers could save $520 million over ten years by killing it.[34]

Then-House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, now vice president and managing director at Moelis & Company, said the stealth effort was just “reflecting the reality. This check off on your tax form is just going into a fund that is not really that relevant at this point.”[35]

Republicans succeeded in eliminating use of the fund to pay for party conventions in 2014. Reformers had pressed Obama on his 2008 promise that if elected, he would make the fund functional again. Wertheimer went to the White House early in Obama’s first term to meet with policy adviser Norm Eisen and work out a proposal to take to Capitol Hill.[36]

But Obama’s political team steered him away from fighting for the reform Obama had promised to pursue, Wertheimer said.[37]

In 2012, Obama and his Republican opponent Mitt Romney rejected public money and spent more than $2.3 billion competing for the presidency. [38]

In his second term, Obama confided to big dollar supporters that he had given up. At a February 2012 West Coast fundraiser, Obama “signaled surrender on one of the fights that had drawn him to politics in the first place: the effort to limit the flow of big money,” according to Kenneth P. Vogel in his book Big Money.

“It was jarring to hear such a blunt assessment from a politician who had built so much of his identity around the idea that average people could band together to change the world, partly by taking politics back from moneyed special interests.”[39]

The 2016 campaign was all about money – raising it, spending it and condemning it. Fiery candidates accused one another of special interest influence, Super PAC abuses and outright corruption. Their strategies ranged from Hillary Clinton’s star-studded soirees, to billionaire Donald Trump’s “self-financing,” to Ted Cruz’s and Marco Rubio’s corporate sugar-daddies, to Bernie Sanders’ quest for small donations.

From the start, no leading contender – or even long shots except for O’Malley – wanted to dip into what had come to be derided as the loser’s fund.

Explained Christian Ferry, campaign manager for GOP Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, “We would be putting ourselves at a huge strategic disadvantage taking the public financing and having to abide by spending restrictions that come with it. Betting on the potential for success, we didn’t even consider it.”[40]

From the start, no leading contender – or even long shots except for O’Malley – wanted to dip into what had come to be derided as the loser’s fund.

The system’s structural flaws had only grown more acute. The 2016 spending limit in New Hampshire, a critical early state, was set at $961,400 based on the state’s population, and spending in Iowa was limited to $1.8 million.[41] Candidates complained that the system failed to recognize that a strong showing at the start of the campaign was critical in narrowing the field.

System architects also could not have anticipated the cataclysmic 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which legalized unlimited spending by independent groups working in support of candidates. The ruling unleashed the flow of undisclosed “dark money” and made it even less likely that nervous candidates facing a barrage of outside spending would buy into public financing.

The court’s decision appeared to give an early edge to GOP frontrunner Jeb Bush, a lucrative campaign fundraiser with a network of closely-aligned SuperPACs. Bush even delayed formally announcing so that he could legally raise SuperPAC money. Bush’s campaign and its affiliates poured money into the primaries, spending about $150 million. Then, in a stunning turnabout, Bush crashed.[42]

The news media acknowledged its faulty analysis of money’s role in the primaries. As TIME magazine editor Nancy Gibbs put it in a talk on Super Tuesday, “The idea that this election was going to be determined by George Soros or the Koch brothers or Sheldon Adelson, if that was ever part of the narrative, then yes, I think that has demonstrably been proven wrong.”[43]

Trump’s emergence further distorted predictions. The billionaire Republican declared that he would keep his campaign clean by self-financing and had loaned his campaign $36 million by the end of March.[44] (This decision also disqualified Trump from receiving any public money, since the law limits the amount of personal wealth candidates may invest in their campaigns). As Trump headed toward the GOP convention, he labeled likely Democratic nominee Clinton “Crooked Hillary” because of her ties to Wall Street and history of money controversies.

Trump’s attacks only added to his appeal. Average Americans saw no problem with a wealthy man spending millions to win an election, polls showed. As Brookings scholar Darrell M. West explained in an analysis of billionaire candidates, “In an age of rampant citizen cynicism, voters see them as white knights who are too rich to be bought.”[45]

Trump, in fact, was accepting some private contributions – about $12 million by March’s end – and he benefitted from a small amount of SuperPAC spending. [46]

As he headed toward the nomination, big money donors like Sheldon Adelson considered how they could support him most effectively without running afoul of his SuperPAC condemnations. Trump’s total campaign spending reached $47 million by the end of April, but more than any candidate in American history, he benefitted from unpaid news coverage spawned by his incendiary comments.[47]

While he questioned his opponents’ integrity, Trump’s muddled campaign money picture presented its own ethical dilemmas. Trump’s campaign relied on Trump-owned businesses for services, including office space and air travel. Ciara C. Torres-Spelliscy, a campaign finance expert who teaches at Stetson University College of Law and serves as a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, cited Trump’s spending at a spring Common Cause conference as a “walking, talking conflict of interest” that could run afoul of FEC rules on self-dealing if he started using public contributions to pay his own companies.[48] (Trump’s corporate lawyers have tangled with the FEC before and prevailed).

Among Democrats, Hillary Clinton made no apologies as she built a fundraising juggernaut and spent heavily in early states. By April, her traditional fundraising tactics brought in $262.7 million and surpassed the small donor strategy of Bernie Sanders.[49]

Sanders, a Vermont senator and avowed democratic socialist, built a grassroots campaign condemning the “corrupt campaign finance system undermining American democracy.”[50]

But he, too, wanted no part of public money. At one Democratic debate, after NBC’s Chuck Todd asked Sanders why he was not seeking public funds, Sanders called the system “a disaster.”

“Nobody can become president based on that system,” he said. Sanders said he decided the best strategy was to reject SuperPACs and “to ask working families and the middle class to help out in a transformational campaign. And you know what? We got 3.5 million individual contributions, $27 a piece.”[51]

Sanders’ strategy validated the concept behind public financing. Small donations from many contributors, bringing in steady revenue and encouraging wide participation, offer an alternative to big-money donors.

But candidates’ refusal to take public funding further dampened reform prospects, even as public outrage festered. Lawrence Lessig, the Roy L. Furman Professor of Law and Leadership at Harvard Law School, was among those arrested in Washington at an April Democracy Spring protest of campaign finance abuses.

Lessig himself briefly ran for president on a platform of campaign finance reform, and he said he also advised Sanders in a memo to hone in on the issue.

Lessig dropped out of the presidential race in November, 2015 before qualifying with the FEC. Although he supports presidential public financing in principle, he favors more systemic reform to address special interest influence, particularly in Congress.

“It’s a triage, like the patient’s got cancer and is bleeding out on the operating table. Which do you do first? I’m going to worry about the bleeding out.”[52]

On Capitol Hill, Rep. David Price (D-N.C.) believes presidential public financing should be salvaged. Working with a reform coalition, Price and co-sponsor, Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), introduced the Empower Act as a step in “taking our elections back from billionaires and corporations.”[53]A Senate version was introduced by Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.), nephew of the late Rep. Morris Udall (D-Ariz.), a reform champion who ran for president in 1976.

Price said some have forgotten the fund’s importance over the years. “It kind of stands out as a uniquely successful experiment in public financing in American elections,” he said. “I’ve said always that it’s not just a matter of exhorting candidates to accept public financing, it is also a matter of fixing the statute so that it is more in line with what a candidate, even a candidate like Bernie Sanders, is going to need,” he said.[54]

The Empower Act would increase the check-off to $20-per-individual and give candidates $6 in public dollars for every $1 they raised in small donations. Participants would have to agree to limit individual donations to $1,000, down from the current limit of $2,700 per person, and would have to show support in 20 states to qualify. The state-by-state spending restrictions would be lifted.[55]

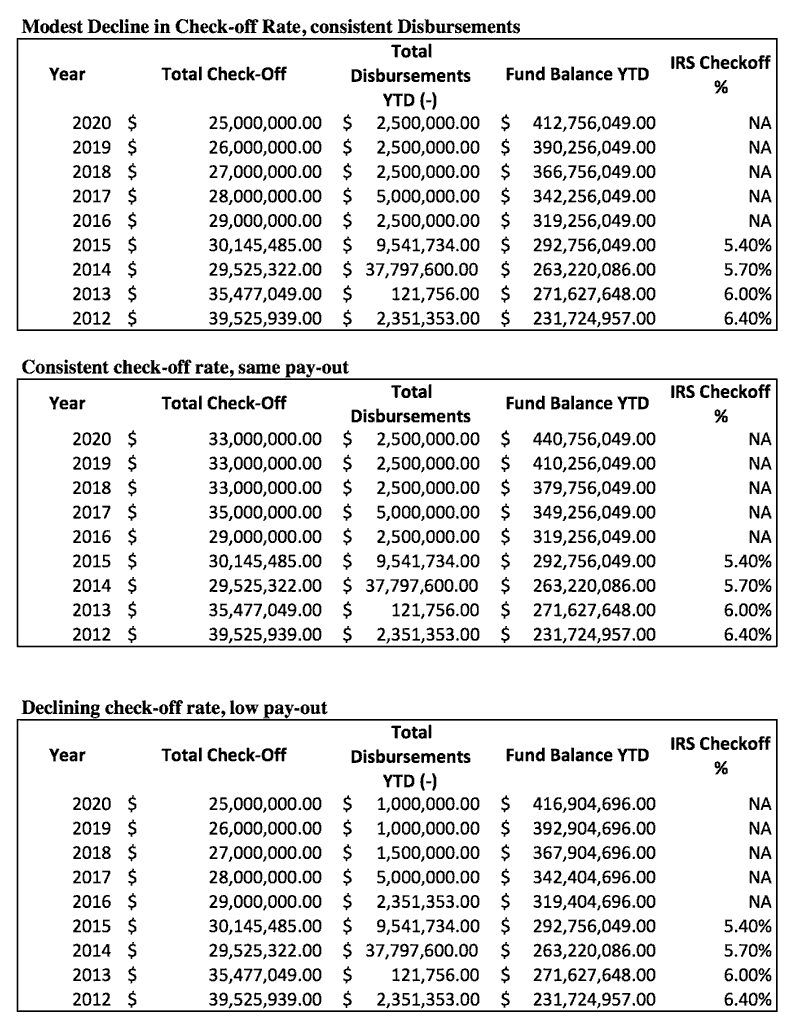

If no major claims are made and no legislative action is taken, the fund could have as much as $450 million by 2020, when the next presidential contest rolls around.

But Price’s bill is stalled in a Republican-controlled House. His principal opponent is Rep. Tom Cole, a conservative from Oklahoma’s 4th District, who wants the law repealed and the unspent funds plowed back into the treasury.

Cole argues that the system is “so radioactive that Republicans at least won’t use it all…It is up to candidates to raise their own money and disclose and play by the rules. But I don’t think the taxpayers need to subsidize them as they go about it. And in this case, it is money that literally ought to just go for deficit reduction or redirect it for some other purpose. It is doing absolutely nothing. Nobody that has a remote chance of becoming president is using it.”[56]

Reformers like Wertheimer say they have “been fighting for years to keep the Republicans from repealing this system. “Go back to the beginning of this story and what happened with Russell Long and Mansfield, and you will know why it is very, very important not to have this system repealed because it provides a framework for fixing the system.”[57]

Even with fixes, more clarity is needed from the U.S. Supreme Court. Calls have mounted for the Court to reconsider Citizens United, but other decisions have added to confusion over how to move forward. The Court in 2011, for example, outlawed an Arizona public financing provision known as the “fair fight fund,” which allowed publicly funded candidates to get additional money to counter unexpected spending by privately funded opponents or third parties.

“Until that ruling is undone, it makes it very difficult to design a public financing system that works with Citizens United,” said Torres-Spelliscy.[58]

Ravel said she intends to propose to the commission by year’s end a solution for money left sitting in the Presidential Election Campaign Fund. If adopted, her recommendation would be included in the commission’s annual recommendations to Congress.[59] Ravel, who last year publicly blasted the commission for its ineffectiveness, has little hope that members would agree on a path forward.

Additional primary claims could still trickle in. The FEC in April approved $100,000 in matching funds for Green Party candidate Jill Stein. But if no major claims are made and no legislative action is taken, the fund could have as much as $450 million by 2020, when the next presidential contest rolls around. And a lone employee in the FEC’s audit division will wait patiently for some primary candidate to file the stack of paperwork required to get a dose of public money.

If history is any guide, it will almost certainly be a loser.

Imagine a corroding 1973 Ford Falcon that’s chalked up 200,000 miles. Getting it to hum again takes more than brushing off the cobwebs and filling the gas tank.

Candidates don’t like to lose, and spending limits built into the existing law pretty much guarantee failure.

That’s the challenge facing the Presidential Election Campaign Fund. It hasn’t performed well for years, and even its fans want a makeover. The fund kept spending in check and perhaps more importantly, insulated candidates, incumbent presidents and party leaders from the unrelenting pressure and ethical challenges of raising outside money. Republican Trevor Potter, a former FEC commissioner who supports public financing, points out that former President Ronald Reagan attended three fundraisers while in office to raise GOP money. As of 2013, Potter says, President Barack Obama had attended 226. [60]

The system deserves a fresh start, given public outrage over unchecked spending. But how can it be fixed?

Up the ante. When a candidate gets a donation of up to $250 – like O’Malley’s small donation from Matthew King – the current program matches it dollar for dollar. Experts want to see a larger match. Proposals on Capitol Hill recommend a 6-to-1 match to make the program more attractive to candidates.[61]

Be realistic. Candidates don’t like to lose, and spending limits built into the existing law pretty much guarantee failure. Reformers want to see a realistic assessment of what it costs to run a respectable presidential campaign and find the funding to accommodate it. Scrap the state-by-state spending caps, and build in some accommodation for a candidate suddenly targeted by an avalanche of outside unrestricted spending.

Expand the pot. An income tax check-off has never been an effective funding tool because it requires active engagement. More funds would be generated through a reverse check-off, in which taxpayers check the box only if they do not wish to participate.[62] Former FEC General Counsel Lawrence Noble says the agency also needs to be allowed to more actively explain the program and encourage participation.[63]

View larger image at the FEC, http://www.fec.gov/press/bkgnd/Pres_Fund/Primay_Receipts.pdf

Pre-1976 Activity

| Year | Total Check-Off | Total Disbursements | Fund Balance |

| 1975 | $31,656,525 | $2,590,502 | $59,551,244 |

| 1974 | 27,591,546 | -0- | 27,591,546 |

| 1973 | 2,427,000 | -0- | 2,427,000 |

Available through the FEC, http://www.fec.gov/press/bkgnd/presidential_fund.shtml

Projections based on FEC data found at http://www.fec.gov/press/bkgnd/presidential_fund.shtml

This paper could not have been written without the assistance of Andrew Levine, my research assistant and a Master’s candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School, who helped in tasks large and small throughout my spring fellowship at the Shorenstein Center. I also wish to thank Tom Patterson for his brilliant leadership and edits, and Nancy Palmer, Katie Miles and other staff members for their many kindnesses throughout the program. A special thanks to fellows Johanna Dunaway, Joanna Jolly and Dan Kennedy for their friendship and professor Marion Just of Wellesley College for her encouragement.

[1] Matthew King, interview with author, April 25, 2016.

[2] Matthew King, interview with author, February 15, 2016.

[3] Federal Election Commission, “Presidential Election Campaign Fund Tax Check-Off Chart” (2016). http://www.fec.gov/press/bkgnd/presidential_fund.shtml

[4] Anthony Corrado, interview with author, April 21, 2016.

[5] Federal Election Commission.

[6] “National: Many Feel Loose Finance Rules Help Unqualified Candidates,” Monmouth University Poll, July 22, 2015. http://www.monmouth.edu/assets/0/32212254770/32212254991/32212254992/32212254994/32212254995/30064771087/e3cdcbf1-0f07-4e8d-92f2-fdcd3b9b3986.pdf

[7] Kathleen Joyce Weldon, email to Author, March 28, 2016.

[8] Federal Election Commission, “O’Malley for President, submission to the Federal Election Commission,” (2016). http://www.fec.gov/finance/disclosure/2016MatchingFundSubmissions.shtml

[9] Federal Election Commission, “Presidential Spending Limits for 2016,” (2016). http://www.fec.gov/pages/brochures/pubfund_limits_2016.shtml

[10] David Hamrick, interview with author, February 24, 2016.

[11] Rebecca Ballhaus, “Martin O’Malley to Accept Public Campaign Financing — and Limits,” The Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2015. http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2015/11/19/martin-omalley-to-accept-public-campaign-financing-and-limits/

[12] Judith Ingram, email to author, February 1, 2016.

[13] Federal Election Commission, “2016 Presidential Campaign Finance,” March 31, 2016. http://www.fec.gov/disclosurep/pnational.do

[14] Federal Election Commission, “Federal Election Commission Certifies Federal Matching Funds for O’Malley,” April 6, 2016. http://www.fec.gov/press/press2016/news_releases/20160406release.shtml

[15] Ann M. Ravel, interview with author, April 29, 2016.

[16] John Wagner, “O’Malley suspends presidential bid after a dismal showing in Iowa,” The Washington Post, February 2, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/omalley-to-suspend-his-campaign-according-to-campaign-adviser/2016/02/01/4e1a4572-c77c-11e5-a4aa-f25866ba0dc6_story.html

[17] John Samples, editor, Welfare for Politicians? Taxpayer Financing of Campaigns, (Washington: The Cato Institute, 2005), 25.

[18] Michael J. Malbin, “Small Donors, Large Donors and the Internet: The Case for Public Financing after Obama.” In C. Panagopoulos, ed. Public Financing in American Elections (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 41.

[19] Ibid., 257.

[20] Fred Wertheimer, interview with author, February 18, 2016.

[21] Raymond J. L. La Raja, Small Change, Money, Political Parties and Campaign Finance Reform, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2008), 46.

[22] Theodore Roosevelt, Seventh Annual Message, December 3, 1907, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29548

[23] Herbert Alexander, “Funding Presidential Election Campaigns,” USIS – Issues of Democracy, September 1996. http://cfinst.org/pdf/HEA/137_financinpreselectusis.pdf

[24] John F. Kennedy, Statement by the President on Establishing the President’s Commission on Campaign Costs, October 4, 1961, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8371

[25] John Samples, The Fallacy of Campaign Finance Reform, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 196.

[26] La Raja, Small Change, 69.

[27] La Raja, Small Change, 72.

[28] Wertheimer, February 18, 2016.

[29] Herbert Alexander, “Financing the 1972 Election,” (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1976), 35.

[30] Internal Revenue Service, Annual Report 1974, (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1974) 11.

[31] Federal Election Commission, “Presidential Election Campaign Fund Tax Check-Off Chart.”

[32] John Samples, “The Failure of Taxpayer Financing of Presidential Campaigns,” in Welfare for Politicians? Taxpayer Financing of Campaigns, ed. John Samples (Washington: The Cato Institute, 2005), 233.

[33] Adam Nagourney and Jeff Zeleny, “Obama Forgoes Public Funds in First for Major Candidate,” The New York Times, June 20, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/20/us/politics/20obamacnd.html?_r=0

[34] Pete Kasperowicz, “Next up for House Rules: ending taxpayer funding for presidential campaigns,” The Hill, January 21, 2011. http://thehill.com/blogs/floor-action/house/139245-next-up-for-house-rules-ending-taxpayer-funding-for-presidential-campaigns

[35] Eric Cantor, interview with author, February 23, 2016.

[36] Fred Wertheimer, interview.

[37] Ibid.

[38] John Nichols and Robert M. McChesney, Dollaracracy, How the Money-and-Media Election Complex is Destroying America, (New York: Nation Books, 2013), 36.

[39] Kenneth P. Vogel, “Big Money, 2.5 Billion Dollars, One Suspicious Vehicle, and a Pimp – On the Trail of the Ultra-Rich Hijacking American Politics,” (New York: Public Affairs, 2014), IX.

[40] Christian Ferry, interview with author, February 24, 2016.

[41] “Presidential Spending Limits for 2016,” Federal Election Commission, January 2016. http://www.fec.gov/pages/brochures/pubfund_limits_2016.shtml

[42] “Which Presidential Candidates are Winning the Money Race,” The New York Times, April 21, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/us/elections/election-2016-campaign-money-race.html

[43] Nancy Gibbs, “The Disintermediation of Media and Politics,” (presentation, Shorenstein Center lecture, Cambridge, MA, March 1, 2016).

[44] “Presidential Campaign Finance Summaries”, Federal Election Commission, March 31, 2016. http://www.fec.gov/press/bkgnd/pres_cf/pres_cf_Even.shtml

[45] Darrell M. West, “Billionaires win when they run for office around the world,” Brookings Institution, March 22, 2016. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/fixgov/posts/2016/03/22-billionaires-win-elected-office-west#.VvbXpc-pM0Y.email

[46] “Donald Trump Fundraising Totals,” Open Secrets, April 21, 2016. https://www.opensecrets.org/pres16/candidate.php?id=N00023864

[47] Marilyn Thompson and Andrew Levine, “How Trump Trumped the TV Networks,” U.S. News & World Report, April 13, 2016. http://www.usnews.com/news/blogs/data-mine/articles/2016-04-13/how-donald-trump-trumped-the-tv-networks

[48] Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, “Plutarchy, Race, and the 2016 Election,” (Panel conversation at Common Cause: Blueprint for a Great Democracy, Washington, DC, March 8, 2016).

[49] “Which Presidential Candidates Are Winning the Money Race,” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/us/elections/election-2016-campaign-money-race.html?_r=0

[50] “Transcript of the Democratic Presidential Debate,” The New York Times, February 5, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/05/us/politics/transcript-of-the-democratic-presidential-debate.html

[51] Ibid.

[52] Lawrence Lessig, interview with author, February 11, 2016.

[53] “Udall, Price, Van Hollen Introduce EMPOWER Act to Modernize Presidential Campaign Public Financing System,” Senate Press Release, May 7, 2015. http://www.tomudall.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=1957

[54] Rep. David Price, interview with author, February 16, 2016.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Tom Cole, Interview with author, February 26, 2016.

[57] Fred Wertheimer, interview.

[58] Clara Torres-Spelliscy, interview with author, March 10, 2016.

[59] Ann Ravel, Interview.

[60] Trevor Potter, “The Money in Politics Disaster” (Presentation at “Red, White, and on the Brink” Plenary Session, Independent Sector National Conference, Miami, FL, October 28, 2015).

[61] Task Force on Presidential Nomination Financing, “Participation, Competition, Engagement: How to Revive and Improve Public Funding for Presidential Nomination Politics,” (Washington, DC: The Campaign Finance Institute, 2003).

[62] Ann Ravel, interview.

[63] Lawrence Noble, interview with author, April 27, 2016.

Videos

Commentary