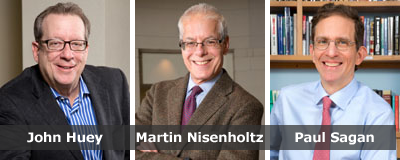

John Huey

Editor-in-Chief, Time Inc., 2006-12

Shorenstein Fellow, Spring 2013

Martin Nisenholtz

Senior Advisor, The New York Times Company

Shorenstein Fellow, Spring 2013

Paul Sagan

Executive Vice Chairman, Akamai Technologies

Shorenstein Fellow, Spring 2013

About the Project:

The Riptide project was conceived and executed at the Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy by three Shorenstein Center Fellows during the Spring 2013 semester: John Huey, Martin Nisenholtz and Paul Sagan. The Riptide website was designed by Joshua Benton and is hosted by the Nieman Foundation. To learn more about Riptide, visit digitalriptide.org for videos, interviews and full text of the project.

From the Introduction:

For most of the 20th century, any list of America’s wealthiest families would include quite a few publishers generally considered to be in the “news business”: the Hearsts, the Pulitzers, the Sulzbergers, the Grahams, the Chandlers, the Coxes, the Knights, the Ridders, the Luces, the Bancrofts—a tribute to the fabulous business model that once delivered the country its news. While many of those families remain wealthy today, their historic core businesses are in steep decline (or worse), and their position at the top of the wealth builders has long since been eclipsed by people with other names: Gates, Page and Brin and Schmidt, Zuckerberg, Bezos, Case, and Jobs—builders of digital platforms that, while not specifically targeted at the “news business,” have nonetheless severely disrupted it.

Reasonable people can—and do—debate whether the replacement of legacy media by new forms of information gathering and distribution—including citizen journalism and smartphone photojournalism, crowdsourcing, universal access to data and, of course, a world awash in Twitter feeds—makes democracy more or less vulnerable. Usually the argument is reduced to a couple of symbolic questions: Who’s going to pay for the Baghdad bureau? Who’s going to replace the watchdog function at city hall traditionally provided by healthy metro newspapers?

On the national level, the owners of the big legacy news businesses have fought fiercely against the disruptors, often with the effect of a frustrated ocean swimmer flailing against a fierce rip current. They have waged legal battles over “fair use”; they have lobbied against anti-competitive behavior; and in many cases they have yielded to the current, creating substantial digital advertising businesses with hundreds of millions in revenue dollars of their own. And at least three big news players—The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Financial Times—all have built emerging models that rely substantially more on consumers paying for their digital products than merely relying on digital advertising. Other legacy news businesses—CNN, Fox News, CBS’s 60 Minutes to name three—also continue to operate with highly profitable margins.

But with each digital click upward in Moore’s Law (processing power) and Metcalfe’s Law (network power) the tide of technological disruption has only risen, washing many of the legacy swimmers further out to sea, or at least diminishing their financial prowess. The summer of 2013 saw two particularly seminal events that highlight the acute situation legacy journalism companies find themselves in today: The Boston Globe sold for a mere $70 million to the owner of the Boston Red Sox (after once selling to The New York Times for $1.1 billion), and The Washington Post Company stunned the journalism world by selling its iconic newspaper to one of those very names we mentioned at the outset: Amazon founder Jeffrey Bezos.

The choice of the riptide metaphor—or the rip current to be strictly accurate—is deliberate. The recommended survival technique against a rip current in the ocean is to quickly move sideways outside the current, but that’s been easier said than done in the news business, just as it is in the open sea. We chose the metaphor to represent what happened to the news business: When successful, pre-digital players who had learned to swim out to sea and return safely with confidence and regularity found themselves over time confronting a stronger and stronger force that made it more and more difficult to get back to shore. And just like a school of swimmers caught in a real riptide, even some of the best-prepared and forward-thinking media companies were swept away no matter how hard they tried to survive.

Visit the RIPTIDE site for full text, videos and transcripts.